The Japanese intellectual who inspires Chinese women

Millennials and younger Gen-Zers are having a feminist awakening in post–#MeToo China, despite a conservative backlash and a government increasingly hostile to the movement. Their unlikely hero is a 74-year-old Japanese provocateur.

“With restlessness and excitement, feminism will keep growing. Plunging into the turbulence, swept along by the surging waves, making new waves in it, how can experiences like this not make one restless and exultant?”

—Chizuko Ueno, 40 Years of Feminism

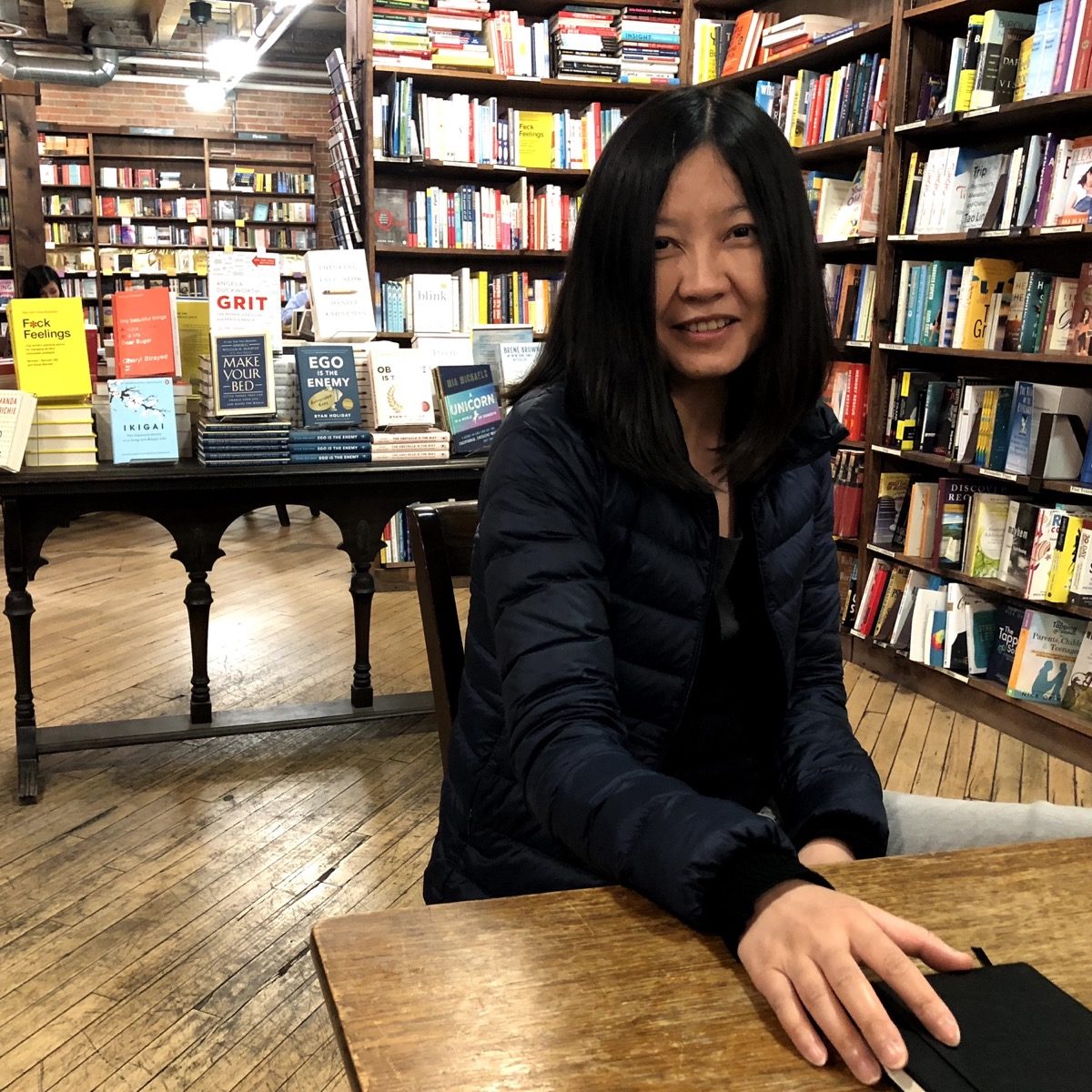

In 2019, Zhū Chēnyáo 朱琛瑶, a 27-year-old book editor based in Shanghai, came across a video on Bilibili.com with more than 10 million views. It featured a speech given by a woman professor at the opening ceremony for incoming students at the University of Tokyo earlier that year.

Standing at the podium with an all-male cohort of college deans sitting stern-faced behind her — she was the only woman among the 15 deans at the university — the professor, in a calm, soft voice, began her speech by recounting a Tokyo Medical University gender-related enrollment scandal exposed a year earlier, and enumerated one issue after another — gender gaps in university enrollment and employment, discriminatory perceptions and expectations of students based on gender, and sexual assaults on campus — that highlighted gender inequality in Japan’s higher education and its broader society.

“What awaits you in the future is a society that does not necessarily reward someone who works hard,” she said to her young audience. “Feminist thought does not insist that women should behave like men or the weak should become the powerful; rather, feminism asks that the weak be treated with dignity as they are.”

The professor’s speech astonished Zhu. “On occasions like this, speakers would usually give inspirational talks, promising the students a great future if they work hard, but that’s not what she did,” Zhu told The China Project. “It’s rare to see such brutally honest remarks that coddle no one’s feelings.”

That was the first time Zhu and many in China heard about Chizuko Ueno, a 74-year-old sociologist and professor emeritus at the University of Tokyo, although Ueno’s books have been translated into Chinese since as early as 1991. In 2021, Understanding Feminism, a slim illustrated book Ueno co-authored with manga artist Eiko Tabusa, came out in China. It sold 150,000 copies within the year and more than 1.25 million over time. Douban, China’s leading platform for book, music, and film reviews, listed the book on its 2021 Books of the Year list.

That’s when Ueno exploded in China.

Since then, 17 books authored or co-authored by Ueno — whose name in Chinese is 上野千鹤子 (shàngyěqiān Hèzi) — have been published in simplified Chinese by more than 20 state publishers and private companies, according to Douban. (The review platform listed Letters Between Chizuko Ueno and Ryomi Suzuki atop its 2022 Books of the Year.) In February, a video featuring a conversation between Ueno and three Peking University women graduates went viral and sent her name trending on Weibo — again — which made observers wonder if China had entered “an era of mainstreaming feminism.” Suddenly, publishing companies rushed to get out her next best seller, and it seemed everyone — the media, bloggers, podcasters, and your WeChat friend circle — was talking about the shītài (师太, woman grandmaster) or nǎinai (奶奶, granny) with the kind of enthusiasm they exude for rock stars.

Women’s books boom and feminism in demand

In 2018, the year the #MeToo movement arose in China, late Taiwanese author Lin Yi-Han’s (林奕含 Lín Yìhán) Fang Si-Chi’s First Love Paradise (房思琦的初恋乐园 fáng sī qí de chūliàn lèyuán), a novel based on the author’s own sexual abuse, was published in the mainland and set off a publishing boom of so-called “women’s books,” a marketing category loosely defined as books by, about, and for women. The trend has intensified over the last three years. By 2022, women’s books had occupied half of Douban’s Books of the Year list. Women’s books are so popular that “at book fairs, the hottest titles all have to do with women,” said Zhu, the Shanghai-based editor.

The publishing industry in China, the majority of whose workforce is made up of women, finally has taken notice of the untapped market of women, who have been reading and buying more books than men for years. Data since 2016 from major online platforms where books are sold, such as Dangdang, JD.com, and Douyin, have shown this trend with astonishing numbers — women were responsible for 86.7% of digital book sales on Dangdang, according to data in 2018.

In this boom, Ueno is both a beneficiary and a trendsetter, which is especially remarkable as her writing — feminist theory, cultural analysis, criticism, and academic research — would be normally considered a hard sell to a general audience compared with fiction and journalistic reporting.

“Ueno has lit a little fire in this boom,” said Zhu, who acted as the executive editor for the Chinese edition of 40 Years of Feminism, a collection of Ueno’s writings for popular publications between the 1980s and 2010. “What (these trends) reflect is people’s demand and the reality of our society.”

“I’ve never labeled myself as a feminist, but when I reflect on my thoughts or my views about the world and on certain issues, I am in fact a very firm feminist,” said a Beijing-based book podcaster known to her listeners as Huā Kāimǎ 花开玛. “It’s only that to the general public, feminism is a concept that has just emerged in recent years.”

Hua majored in Chinese literature in her undergraduate and graduate studies, but she did not recall feminism included in her curricula. She read The Second Sex and studied writings of women writers such as Lín Bái 林白 and Yán Gēlíng 严歌苓, but it was Ueno’s Misogyny that made her consciously think of herself as a feminist. She was, in her words, “enlightened.”

“All those things in my mind that had been a jumble of impressions I couldn’t put into words suddenly were clear to me after I read that book,” said the podcaster. “It really is an important book to me.”

Millennials like Hua — she is in her early forties — and the younger Gen-Zers are having a feminist awakening in post–#MeToo China despite a conservative backlash and a government increasingly hostile to the feminist movement. When Ueno came onto the scene armed with feminism, she was met by readers with a huge appetite for intellectual resources and a language to answer these questions and talk about them. And Ueno wowed them — as one reader wrote in their review of Ueno’s Patriarchy and Capitalism on Douban, “How I feel now is like a worker in the 19th century who had just read Das Kapital for the first time.”

Recent data show that young women in China outperform their male counterparts in education, even when some academic programs are not open to female applicants or limit the number of their enrollment. But globally, China is still lagging behind in gender equality, ranking 102nd out of 146 countries on the Global Gender Gap Index 2022. Contrary to their expectations, the best-educated generations of women in China have “encountered excessive gender discrimination and pervasive masculinist sexual norms that openly treat women as sex objects and secondary citizens,” wrote University of Michigan historian Wang Zheng in her essay “Feminist Struggles in a Changing China.”

It is not hard to imagine they would be sensitive to gender inequalities and misogyny, the pervasiveness of which is, if one pays attention, startling. Outraged in the wake of #MeToo, young women are rethinking their day-to-day experiences and raising questions about subtler gender inequalities that their parents would never have thought worth asking.

“There is no feminist who has not come from misogyny. To be a feminist means to engage with and struggle against misogyny. Women free from misogyny (if they really exist) have no reason or necessity to become feminists. Sometimes I hear women claim, ‘I have never been constrained by the fact that I am a woman,’ which actually can be translated into ‘I have been avoiding combating misogyny face to face.’”

—Ueno Chizuko, Misogyny

Finding Ueno

“If I have to give Ueno a label, I’d say she is a role model for women,” Hua Kaima said. “She is a scholar who is able to output a system of her thoughts and research. Her theory is healing for many women and can help them see the reality…through confusion.”

Like Hua, younger feminists, many new to feminism, see a role model — a mentor — in Ueno that they did not have in China, though gender studies was established as a discipline in both China and Japan in the 1980s, and Ueno has been compared to Lǐ Xiǎojiāng 李小江, a pioneer in gender studies in China, as both owe influences to Western schools of thought such as Marxist feminism and psychoanalysis.

Unlike in Japan or in Western academia, however, gender studies has been depoliticized in China’s unique political environment. Chinese gender scholars normally do not identify themselves as feminists explicitly, though they subscribe to feminist principles intellectually.

“Gender studies has been criticized for distancing itself from Chinese feminists’ activism and…has become something circulated internally within academia,” Wú Xiǎoyīng 吴小英 of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) wrote in a paper published in the Journal of Chinese Women’s Studies in 2018. The rise of millennial and Gen-Z activists in the 2010s deepened this break between scholars and activists, wrote Wu, “although they collide with each other often, sometimes resulting in mutual appreciation, and other times, discord.”

In a recent case, Dài Jǐnhuá 戴锦华, a professor at Peking University renowned for her feminist scholarship in literary and film criticism, was criticized after her public dialogue on feminism with Ueno in February. Her detractor, Hóu Qíjiāng 侯奇江, who was a former student of hers, accused Dai of changing her views on feminism and activism according to the political climate.

Under President Xí Jìnpíng 习近平, Chinese feminists have been more marginalized and subject to government crackdowns and stricter censorship as a new generation of activists became more vocal and active in public. The arrest of five young feminist activists in 2015, the permanent shutdown of the feminist platform Feminist Voices (女权之声 nǚquán zhī shēng) in 2018, and the crackdowns of #MeToo in courts and in cyberspace are just a few high-profile cases.

So the catch-22 Chinese feminists (publicly identified or not) face is, those who can publish in mainstream venues cannot discuss gender issues in China freely and honestly, and those who want to, will not be allowed to publish. That is why many Chinese feminist works can sound hollow, devoid of relevancy to daily life. “I’ve long been tired of so many feminist books that rehash obvious reality and ideas again and again but ignore the deeper confusions in real life,” a reader of Letters Between Chizuko Ueno and Ryomi Suzuki wrote in their review on Douban.

Ting Guo, an assistant professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, described the predicament in an interview with the Guardian, “We cannot really directly describe what we want to say, using the word that we want to use, because of the censorship, because of the larger atmosphere. So people need to try to borrow words, mirror that experience in other social situations, in other political situations, in other contexts, in order to precisely describe their own experience, their own feelings, and their own thoughts.”

Ueno, perhaps inadvertently, has become that mirror for Chinese women. Insulated to a certain extent from censorship and conservative and nationalist attacks because she does not directly write about China’s social issues, the Japanese scholar is able to play the role of a medium for Chinese feminists.

And it so happens that Ueno writes from Japan, an East Asian country that shares many common cultural influences with China and had a period of fast economic development in recent history that mirrors China’s in many ways. The two countries, along with South Korea, rank closely in the gender gap, according to the Global Gender Gap Index 2022. “Women’s circumstances have a lot of overlap” in these three East Asian countries, said Zhu. In fact, South Korean feminist works like Kim Ji-young: Born 1982, a feminist novel by Cho Nam-joo, are also well received in China. In Ueno’s case, despite the fact that most of her theoretical thoughts are “borrowed” from the West, she is better known in China than many Western big names in feminism and gender theory.

But cultural affinity is not the whole story. An activist at heart — she has been in the trenches of the feminist movement in Japan since the 1980s — Ueno has always tried to reach a mass audience with her message. She chooses very different forms and styles for her books — the theory-heavy Capitalism and Patriarchy, the lighthearted conversational Understanding Feminism and Conversations Between Ueno Chizuko and Reiko Yuyama, and everything in between — so she can attract a wide range of readers, from serious scholars and students to the most casual readers who happen to pick up her books because of their provocative titles.

“I call these two types of books the hard and the soft, the A-side and the B-side, and the upper body and the lower body,” she wrote in Letters.

But her reputation goes beyond that of a popular writer. In Japan, she is known for being a provocateur, who has been called the “four-letter scholar” (the Japanese for “vulva” can be written with four katakana characters); “sociology’s Kaoru Kuroki,” which likened her to a former adult-film actor known for her outspokenness on sex and society; and “the most feared woman in Japan” for her willingness to name names. She has straight-up called Japan’s gender inequality a “human disaster.”

“I thought, so what? As long as it sells,” she wrote in Letters. “My critics can try to write a best-seller themselves.”

“Look straight into your hurt and pain. When in pain, cry out. The dignity of a human being starts here. Be honest and don’t lie to yourself. If a person can’t trust and respect one’s own experiences and feelings, how can one trust and respect others’ experiences and feelings?”

—From Letters Between Chizuko Ueno and Ryomi Suzuki

Crying out the pain

In China, readers find Ueno’s effrontery refreshing and inspiring at a time when feminists are stigmatized as “women’s fists,” or nǚquán 女拳, and feminist voices have been attacked as “stoking the conflicts between genders.” Ueno even earned the reputation for possessing a dúshé 毒舌, literally, “poison tongue,” which she shares with public figures like Jīn Xīng 金星, the famously outspoken transgender choreographer and host.

“She has been attacked over the years but never wavered,” Zhu said. She has “walked the walk, and that is admirable.”

One of Ueno’s most famous “gold lines,” as readers call her highly shareable aphoristic quotes, is “When in pain, cry out.” The past five or six years have given young people plenty to cry out about. This past summer, China’s youth unemployment rate reached a record high of 21%, with the government recently announcing that it would suspend releasing future data on youth unemployment. Young people are growing suspicious of the promise of meritocracy, and many are rejecting “involution,” a pressure-cooker-style competition, and opting for quitting, “lying flat” (躺平 tǎng píng), or “letting it rot” (摆烂 bǎi làn), as they read Michael Sandel and David Graeber.

Then there is the government’s pressure for them to reproduce as the population declines with new policies like the three-child policy, a 30-day wait period for divorce (which raised concerns about domestic violence), and policies discriminating against working women. Awkwardly, the interest to have children stayed low and during the most oppressive months of the COVID lockdowns last year, the “last generation” became a trending hashtag, as young people defied the authorities’ threats of retribution targeting their future offspring.

To these young people, Ueno’s liberal conviction for personal freedom and her intersectional feminism that calls for solidarity of the marginalized are especially comforting and empowering. (Ueno’s recent research has been focused on the aging population.) The septuagenarian professor, unmarried and childless by choice, also shows young women the possibility of living a dignified life without conformity.

“In the Douban app, many readers have marked this line, ‘The society we pursue is one where the weak are respected as the weak,’” Zhu said. “I think everyone can relate to this line.”

One of the things Ueno talks about that resonates most with many readers is the “fear of weakness” that high-achieving women “elites” often internalize. The mentality makes them afraid to admit to their own weakness and pain while looking down upon women such as stay-at-home moms who are not as “accomplished” as they are. Ueno attributes it to neoliberalism, but in China, the same mentality was internalized by generations of women of the “new China” under the influence of revolutionary propaganda prioritizing productivity and progress.

“Ueno’s writing actually liberates women from this bondage,” Hua said. “I think her writing has a kind of humanist care.”

In her writing, readers are let in to see her own weakness and vulnerability, and that is empowering. “Even a senior feminist scholar like Ueno seems to have confusions and contradictions, so what are we regular people afraid of?” wrote a reader about Letters on Douban.

“I once read a reader’s comment saying that Professor Ueno was their harbor,” said Zhu about the feedback she received from readers of 40 Years of Feminism. “I hope everyone who has read this book will take away this: No matter what predicament you are in, someone knows it and will speak up for you, so, do not fear, because you, too, have the power to resist.”