This Week in China’s History: August 27*, 1689

It was a modest setting for a meeting of two great empires: a wooden fort, isolated in the forests of eastern Siberia, inhabited by just a few hundred inhabitants, fur traders, and soldiers. In the summer of 1689, Nerchinsk became the site of the treaty commonly regarded as the first modern treaty between China and a European state. More than that, in the analysis of historian Peter Perdue, citing Mongol, Portuguese, Polish, Siberian, and French influences — in addition to the obvious Manchu and Russian ones — “It was not just a two-sided contract, but a global agreement.”

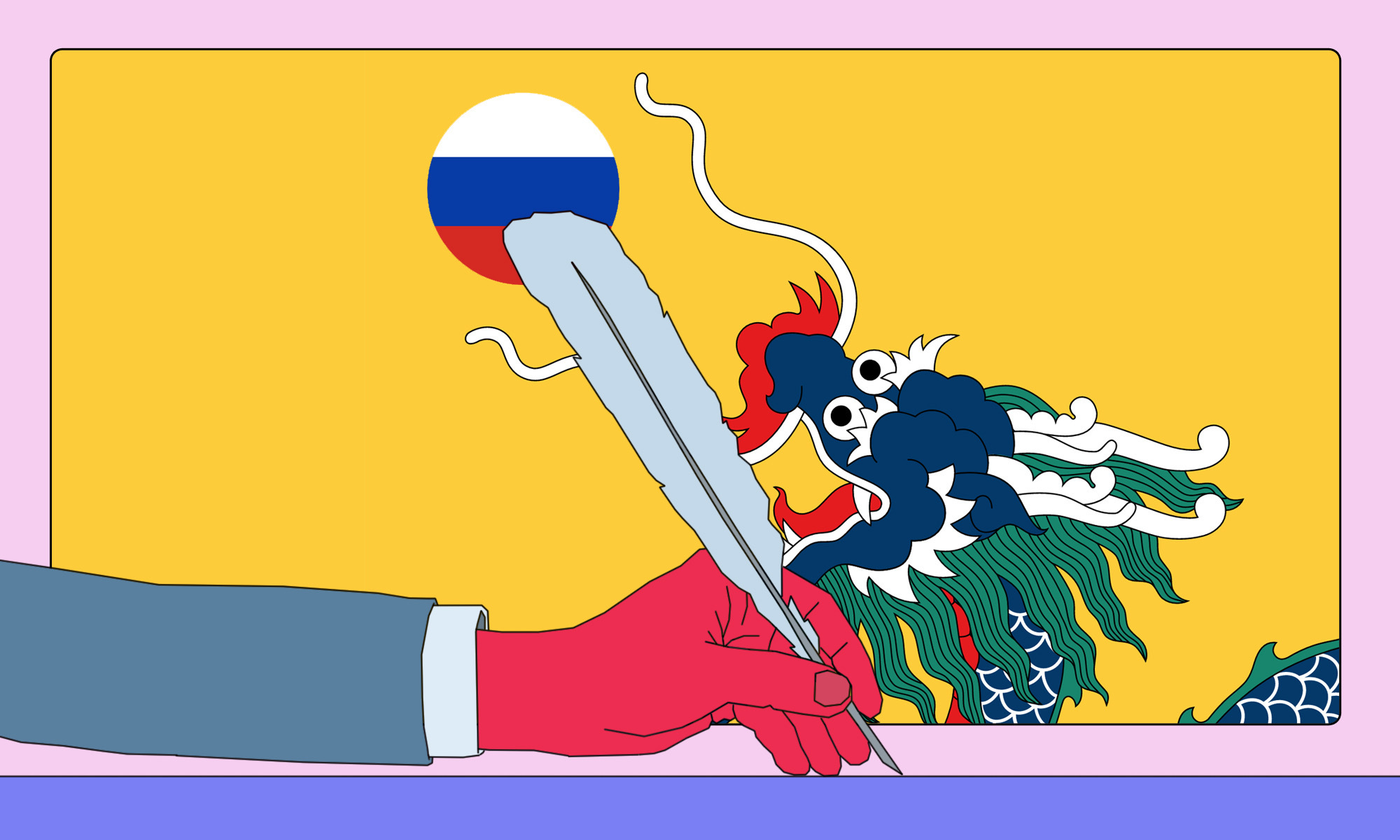

China and Russia — and their empires — dominate the northern tier of Eurasia, together spanning from the Pacific to (nearly) the Atlantic. Russia’s first emissary to Beijing had visited in 1618, as the Ming was declining, but it had not resulted in ongoing relations (the Ming emperor’s letter proposing a trading relationship was delivered to Russia’s tsar, but it went untranslated for 40 years, by which time the Ming had fallen).

In the 17th century, both states were near their largest extent under the Manchu Qing and Russia’s Romanov dynasty. For decades, the Manchus and Russians had encountered one another on their frontiers. Meanwhile, Russian settlers — trappers, traders, soldiers, diplomats — continued their eastward movement across Siberia toward the Pacific. By the 1630s, they were in a territory that is today part of China, building fortresses, like Nerchinsk and Albazin, and engaged with tribes allied with the Manchus. Manchu armies pushed the Russians back — twice in the 1650s — while embassies and trade missions from Moscow made their way to Beijing, hoping to open trade.

For 30 years, the frontier — and the people along it — ebbed and flowed between the two states. Borders were uncertain and changeable; people could change from Qing to Romanov subjects and back again, all the while sending confusing and often conflicting reports back to their capitals. Not until the 1680s did the Russian and Qing sides open negotiations to fix the border, in part because it took until then for the Manchus to consolidate their conquest of China after the War of the Three Feudatories.

Both sides wanted to settle the frontier issue so they could focus on other military priorities. The Russian state was taking on the Crimean Khanate, and lacked the surplus time or energy to deal with having to rebuild fortresses every few years after Qing raids. The Qing wanted to prevent Russia from allying with the Zunghars under Galdan, with whom the Manchus had been fighting for some time. With other priorities demanding their attention, both sides were looking to compromise.

The will to negotiate was important, but the success of any negotiations was far from guaranteed, especially between two sides so seemingly unlikely to meet in the middle. “Neither of the imperial rulers accepted any principles of equality between sovereign states,” Perdue goes on, “both believing strongly in subordination of others as vassals, subjects, or tributaries. They did not share a common language of diplomatic communication, and they had no common religious ties, significant trading relationships, or extensive mutual cultural or geographic knowledge. Each of them knew much more about their common enemies, the pastoral nomads of Mongolia, than they knew about each other. Both Qing and Russian officials started from a position of extreme distrust, since they had fought one another and each side rightly suspected the other of intriguing against it.”

How, then, did they wind up concluding a treaty that can be held up as one of the most significant diplomatic achievements of the early modern era?

Russia’s eastward advance had reached the Pacific Ocean in 1639, and soon found that the Amur River valley offered riches — farmland, furs, forests, and even gold — that might sustain the settlement of the entire region. The Romanov dynasty constructed fortresses at Albazin, in 1650, and Nerchinsk, in 1654, to oversee the region’s development.

The Manchus, though, had different ideas, as they expanded their empire in the opposite direction. Both the Russians and Manchus were negotiating with the Tungusic and Mongolian tribes that had inhabited the region for centuries. After decades of skirmishes and encounters, and a Qing siege of the Russian settlement at Albazin, the Qing Kangxi Emperor announced an embassy seeking a peace treaty. The delegation was headed by two Manchus and accompanied by two Jesuit priests.

The Jesuits — Frenchman Jean-François Gerbillon and Portuguese Tomé Pereira — were critical to the mission for two reasons. They could translate between the two sides, for one thing, conducting negotiations in Latin with the Russians’ Polish interpreter, but even more crucially, both the Qing and Romanov sides trusted them, something that they could certainly not say about each other. When the two parties reached the banks of the Shilka River — each on opposite sides — it took four days before a meeting could be arranged.

When they did meet, seated at opposite sides of a tent, they made claims to the land. The Qing based their claim on Genghis Khan’s 13th-century conquests; the Russians pointed to their present occupation. Negotiations soon broke down and the Russians became suspicious of the Jesuit mediators, asking that the talks proceed in Mongolian so that the Jesuits could not collude. Insulted, the Qing side prepared to return to Beijing.

In fact, both sides seemingly found every opportunity to take offense and find fault with their counterparts, but just as the conference seemed over, each side returned to the intractable problem of the border and the fluid loyalties of the people who lived there. Without a treaty that would delineate the border and — just as importantly in Perdue’s view — pin down “the loyalty of mobile peoples in the region,” the two empires would spend unaffordable resources on the region.

After four more days of hard negotiating, only one issue remained: the Russian fortresses at Nerchinsk and Albazin, with the Qing insisting they both be razed and the Russians demanding they remain intact and in Russian hands. Additional territorial concessions, and a Qing siege, sparked compromise: Nerchinsk would remain Russian; Albazin would go.

The Treaty of Nerchinsk was agreed to in principle, then written in Latin for discussion by both sides. Finally, on August 27*, it was translated into Latin, Mongolian, Manchu, Chinese, and Russian, and signed by both sides. The border agreed to in 1689 remained for nearly 200 years; the 1858 Treaty of Aigun and the 1860 Convention of Peking took territory north of the Amur and along the Pacific coast for Russia, but the western boundary established by the Nerchinsk treaty remains in place today.

Peter Perdue calls the Nerchinsk treaty “a near miracle” negotiated in a remote region between two sides that distrusted each other and with deeply different conceptions of both diplomacy and politics. Shared common interest, willingness to compromise, trusted intermediaries, the threat of force, and even some desperation all worked together to achieve a positive outcome.

The Nerchinsk treaty was far from perfect, but in today’s era of deep distrust between many states, perhaps it provides some hope that “astute negotiators can span even very wide cultural gaps and create peace in inauspicious circumstances.”

And about that asterisk: The treaty was signed on August 27, according to the Russian sources, but Russia remained on the Julian calendar until the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 (when the calendar changed, Russia skipped from February 1 to February 14, 1917…the first two weeks of February 1917 never happened in Russia!). In 1689, the Julian calendar was 10 days behind the Gregorian calendar I use for Western dates in this column. The Russians at the time called it August 27, and to the Qing it was Kangxi 28, but this week in China’s history was September 6, 1689: the Treaty of Nerchinsk.

This Week in China’s History is a weekly column.