This is book No. 35 on Paul French’s Ultimate China Bookshelf.

Blurbs:

“Peking Story is a poignantly written requiem for Old Peking — the city whose death is symbolic of the death of China’s ancient culture and civilization.”

—Nien Cheng, The New York Times Book Review

“Kidd’s pieces have been a double illumination. Their intimate domestic lanterns shed light on the dark side of the moon and, exotic and informational interest aside, glow in their own skins, as art. They are simple, graceful, comic, mournful miniatures of an ominous catastrophe, the unprecedently swift death of a uniquely ancient civilization.”

—John Updike

“Kidd paints indelible sketches of an aspect of Chinese life gone forever. A finely wrought account.”

—Booklist

“For Americans who travel to Beijing or who are interested in the city as it was before the revolution, this book will give a new dimension to their understanding and enjoyment.”

—New York Times

About the author:

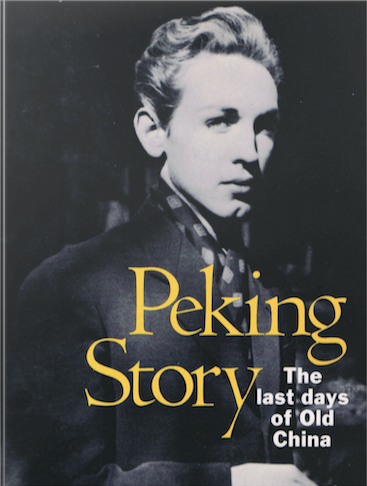

David Kidd (1927–1996) originally came from Kentucky, studied Chinese at the University of Michigan in 1946, and went to Yenching University on an exchange to study Chinese poetry and teach English. He spent some time living in a traditional courtyard with his Chinese wife. In 1950, Kidd and his wife left for the United States. She pursued a career as a physicist in California and he immersed himself in Chinese art circles in New York.

He taught at the Asia Institute until 1956, when he moved to Japan. There he taught at Kobe and Osaka universities and began collecting Chinese and Japanese art and antiques. He divorced his first wife and settled down in Kyoto with Yasuyoshi Morimoto. Kidd founded the Oomoto School of Traditional Japanese Arts. His account of the last days of the ancient Chinese regime was published in 1960 as All the Emperor’s Horses and was reissued in 1988 as Peking Story. He died in Honolulu in 1996.

The book in 150 words:

For two years before and after the 1949 revolution, David Kidd lived in Beijing. He was married to Aimee Yu, the daughter of an aristocratic Chinese family, and was living in some comfort and seclusion on a hutong alley. With Yu, he came to see one of the last traditional families of Beijing in situ. Peking Story was serialized by the New Yorker in 1955, first published as a book in 1988, and then reprinted in the early 2000s as a New York Review of Books classic.

Your free takeaways:

I used to hope that some bright young scholar on a research grant would write about us and our Chinese friends before it was too late and we were all dead and gone, folding into the darkness the wonder that had been our lives. Ultimately the task fell to me.

Late January of 1949, Peking surrendered gracefully to the ever victorious Communist Army, and one day soon after, my fiancée — a Chinese girl — telephoned me to say that her father, who had been ill for a long while, was dying. We must marry immediately, Aimee said, or face the prospect of waiting out at least a year of mourning, as Chinese custom demanded. It seemed unfeeling to hold a wedding at such a time, and there was no way of guessing what the Communist authorities would say to a marriage between the daughter of a “bureaucratic-capitalist” Chinese and an American teacher, but the future was so uncertain that we decided we must go ahead. Aimee’s family, when consulted, agreed. However, since we could not be sure we were not bringing some sort of trouble on them, we planned to keep the marriage a secret, at least for a while.

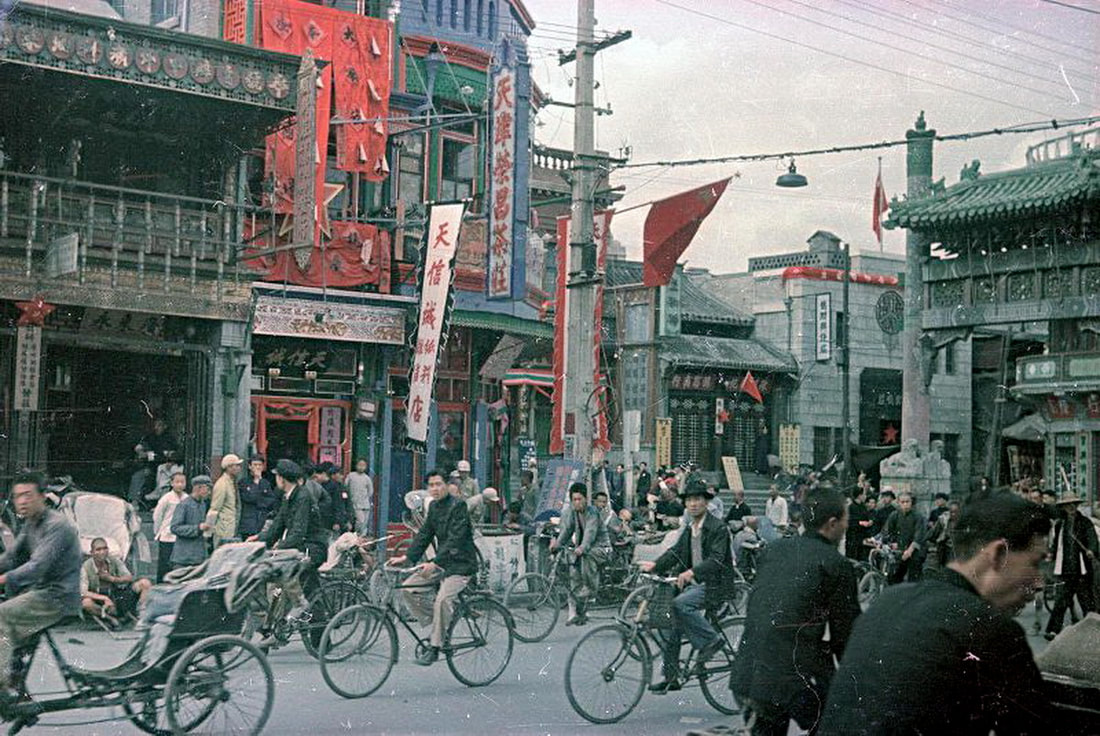

Peking was a great walled and moated medieval city through which pulsated a life in what was considered the world’s largest empire. Within its walls lay the Forbidden City, the center from which imperial power reached out to all of China, and from there, the world.

Aunt Chin often spoke cryptically, alluding to some old Chinese saying or myth, but she was truly a wise person. As they saw their friends and neighbors degraded by the reform of the “New China,” as the only life they had known crumbled and blew away like dust, as the Yu family had to relocate from the home that had been theirs for four centuries, as Aunt Chin faced being homeless but would eventually find shelter in a temple, she would postulate: Houses and people and tables and chairs move and change of themselves, following destinies that cannot be altered. When things change into other things or lose themselves or destroy themselves, there is nothing we can do but let them go.

Why this book should be on your China bookshelf:

Kidd’s Peking Story is one of the best accounts we have of the crucial interregnum period between the end of the Chinese Civil War and the consolidation of Communist rule. Revolutionary consolidation is not instantaneous, it doesn’t happen overnight. It takes a while. This was true of the Bolshevik Revolution — the NEP, War Communism, etc. So too it took the Chinese communists some time to consolidate their revolution, even in their new capital of Beijing. So we see Kidd and his wife’s family still living a largely traditional life in terms of their routines, tastes, clothing, and style. Yet the authoritarianism that would become the leitmotif of the People’s Republic of China is creeping into their lives. Radios seized, restrictions on foreign nationals, spy mania, local cadres nosing their way into people’s lives. So we have the contrast of the sprawling hutong courtyard, visits to ancestral temples, moonlit picnics, servants, opulent ceremonies, lavish entertainments, and cherished antique heirlooms — and the new communist regime.

But perhaps what most stays with the reader is the cast of characters Kidd encounters — a cast at a time of change and whose fortunes will be starkly different: The disheveled Reverend Feng, who performed his wedding ceremony in unintelligible chants, whose beliefs are now highly problematic; the family’s once-trusted cook who turns into a street beggar after being sued in court; a Mongolian prince dressed as a Mongolian princess; Kidd’s in-laws, including Aunt Chin, who traces her Manchu roots to an empress of China.

Despite his intense attraction to the aesthetic of old Peking, Kidd was not wholly unsympathetic to the revolution and its broad aims of bettering the lot of the ordinary citizen. But the final portion of the memoir recalls when Kidd returned to Beijing in 1981: the city was unrecognizable, and the living conditions of the remaining Yu family were depressing.

Kidd could have made his book far darker, more morose. Yet he tries to keep a positive attitude, often satirical, to look at the cohesion of the Yu family, held together by their former status and traditions even when brought low by the communist revolution. However, even the most ardent supporter of the revolution would perhaps find a tinge of sadness at the passing of so many rituals and observances, a loss of China’s collective memory through fear. Kidd’s book can be accused of nostalgia for a time when many people in China lived awful lives of desperate and inveterate poverty, but there were bright spots — weddings, parties, celebrations — and he recalls these, too, in minute detail.

Next time:

Barely 30 years after Kidd left China, a young American arrived to head inland to an uncertain posting. The country had changed beyond belief in many ways — a new name, new leaders, periods of turmoil and chaos not so far behind it, an era of supposed advancement and new brighter horizons ahead. And so, a book about learning from China by another Westerner, this time in the 1980s, in the hinterlands…