U.S. lawmakers want to restrict sales of gene sequencing tech to China

Some major American firms stand to lose business if Congress, citing human rights abuses, requires regulation of sales to China.

U.S. lawmakers are proposing new rules to crack down on the sale of American-made gene sequencing technology into China’s booming market, requiring sellers to demonstrate that their products would not abet human rights abuses and prove that buyers are innocent of such abuses in the past.

China’s annual DNA sequencing market was estimated to be valued at 18.3 billion yuan ($2.5 billion) in 2022. When used ethically, gene sequencing has a range of valuable uses from improving cancer treatments and screening newborns for susceptibility to certain diseases, to better understanding how to increase crop yields.

U.S. Senator Marco Rubio (R-FL) introduced the legislation in the Senate in July, proposing a law that also would more closely control U.S.-made gene sequencing tech, and that would place new sanctions on entities blacklisted for “human rights abuses directly or indirectly related to genetic monitoring efforts.”

In the recent past, Chinese authorities and academics have used U.S. software and gene sequencers to conduct genetic studies of ethnic minority populations and develop a process of extrapolating criminal suspects’ physical features from DNA samples, previous reporting showed.

Chinese genomic research giant BGI Group in Shenzhen and the Institute of Forensic Science, which is affiliated with China’s Ministry of Public Security in Beijing, already blacklisted by the U.S. Department of Commerce for human rights violations against Uyghurs, ethnic Kazakhs, and other members of Muslim minority groups, would be put under new sanctions if the legislation passes.

The use of DNA sequencing tech in China has raised alarm among rights advocates, as it occurred during China’s systematic campaign of repression in northwest China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, when, beginning in 2016, the government detained and imprisoned as many as one million Turkic Muslims in what the United Nations described as “crimes against humanity.”

If passed, Rubio’s bill could lend legitimacy to American policies aimed at supporting human rights in China.

“Such legislation would be significant,” Yves Moreau, a professor who researches the role of genomics in mass surveillance at the University of Leuven in Belgium, told The China Project. “It sends a powerful signal to U.S. companies that ‘playtime is over’ regarding the sale of mass surveillance technology to authoritarian regimes.”

Moreau said the proposal to regulate the sale of U.S. gene tech balances out American restrictions aimed at Chinese businesses such as Hikvision for the role the cameras it makes play in the surveillance of Uyghurs — restrictions some critics say arose not as a move to protect human rights but as a salvo in the U.S.-China trade war.

China news, weekly.

Sign up for The China Project’s weekly newsletter, our free roundup of the most important China stories.

In December 2022, Congress barred Americans from working with foreign military, police or intelligence services after two Democrats added an amendment to the Pentagon budget that resulted in Congress changing export control regulations administered by the Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) at the Department of Commerce.

While the administration of President Joe Biden has not moved to regulate gene sequencing tech using that new authority, Moreau told The China Project that those new rules were a possible avenue for preventing Chinese law enforcement from using American-made genomics products for mass surveillance.

“There is significant bipartisan support to regulate the sale of mass surveillance technology to bad actors,” Moreau said. “It seems likely that the Bureau of Industry and Security will eventually have to publish regulations controlling the export of genetic technology.”

Enforcement challenges

Even after the administration of former President Donald Trump moved in 2019 to crack down on the business, gene sequencing technology made by U.S. companies Thermo Fisher Scientific and Promega was bought by Xinjiang law enforcement as late as 2021, The New York Times found.

As the U.S. has added Chinese firms to trade blacklists, Chinese companies have developed strategies to get around so-called “end-user” restrictions that target specific Chinese companies.

“There’s been a lot of effort by the Chinese state and by Chinese businesses to change company names, to try to continue doing business through the same company with a different name, or sell a subsidiary company to another company,” Rian Thum, University of Manchester professor of history told The China Project. ”There’s a lot of work being invested in covering people’s tracks and evading the import and export restrictions.”

Senator Rubio’s new legislation would add various genetic technologies to the Commerce Control List, making the new controls “list-based,” instead of targeted at specific end-users, making it more difficult for Chinese companies or government entities to buy the products.

Publicly available documents reviewed by The China Project showed public security bureaus throughout China bought DNA sequencing tech in recent months from American companies including Thermo Fisher Scientific, Promega, and Illumina.

Not all sales of gene sequencing products in China contribute to rights abuses and, Moreau said, the new rule could slow the availability of the tech in cases where it is being used ethically, such as in testing for coronavirus.

“In the current form, this legislation could create a serious administrative burden on the legitimate sale of biomedical genetic sequencing products to Chinese hospitals,” Moreau said.

U.S. companies cashing in

Major American companies developing genetic sequencing technology have continued investing in China and ramping up sales there in recent years despite U.S. policymakers’ concerns about biotechnology and national security, and human rights advocates’ alarm at the misuse of the technology in oppressing ethnic minorities.

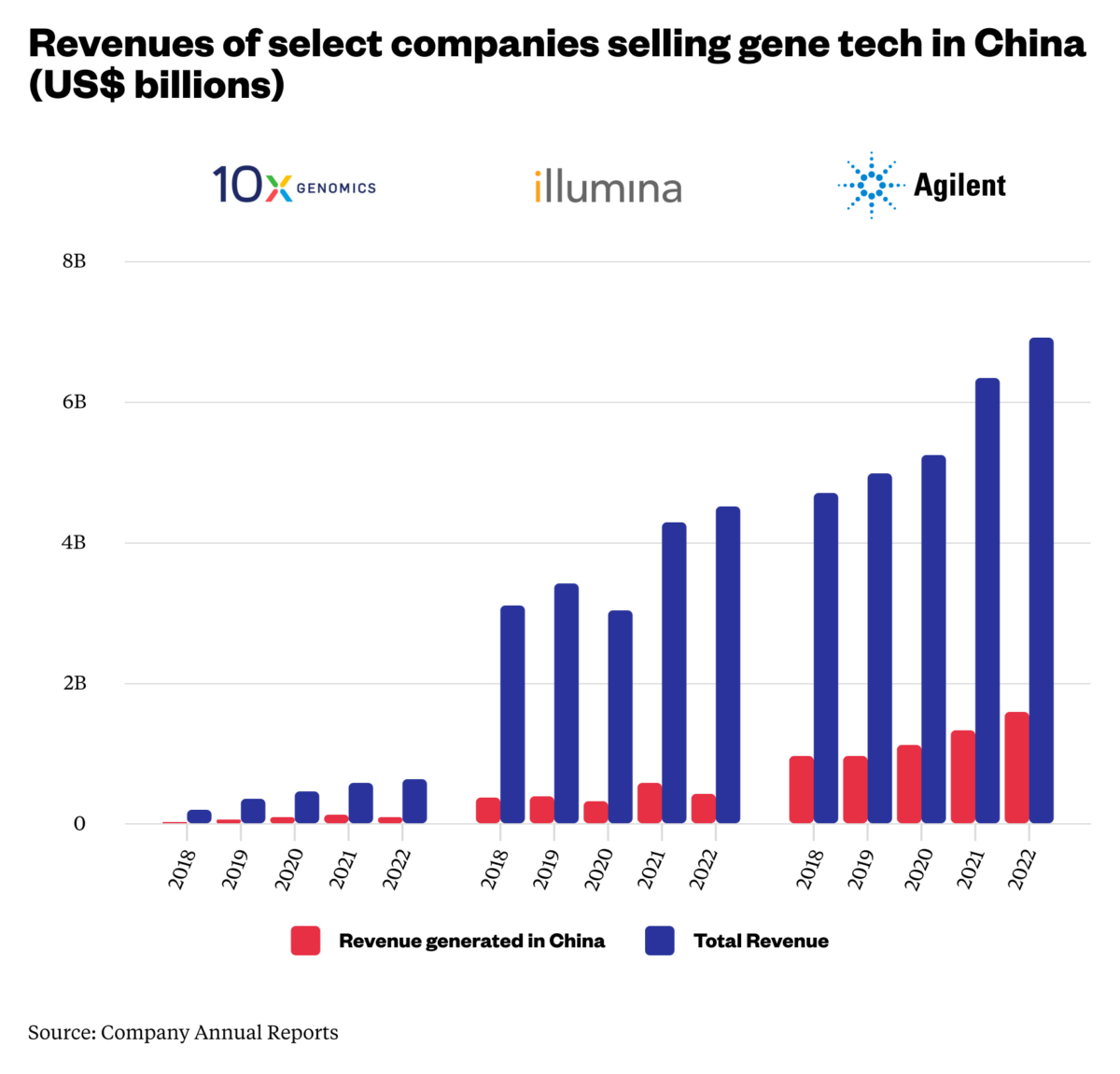

Leading California-based gene sequencing companies Illumina, based in San Diego, and 10x Genomics, based in San Francisco, have seen their revenues in China grow over the past five years along with rising Chinese demand for genetic sequencing technology.

Madison, Wisconsin-based Promega does not publish geographic breakdowns of its revenue, but does have a branch office and an R&D and manufacturing center in China.

Genetic sequencing is the main line of business for Illumina and 10x Genomics, while genomics is just one segment of a broader array of products and services from Thermo Fisher Scientific, based in Waltham, Massachusetts, and Santa Clara, California-based Agilent.

In addition to revenues, some of the U.S. firms have made investments in China that demonstrate a longer-term commitment to serving the market.

“There is no clearer indication of the company’s dedication to the Chinese genomics market than the opening of its first manufacturing site in the country,” Illumina said in November 2022, citing the estimated value of China’s DNA sequencing market at 18.3 billion yuan ($2.5 billion), with a projected compound annual growth rate of 11.4% from 2020-2027.

Illumina’s gene sequencing technology played an important role in China’s use of DNA in state surveillance.

“There’s really no equivalent in terms of the technology and also the quality control in China,” Mark Munsterhjelm, a University of Windsor professor who focuses on racism and ideology in genetic research on indigenous peoples, told The China Project. “The Illumina systems are very important to these phenotyping efforts.”

It’s not just about Xinjiang

While the plight of the Uyghurs at the hands of authorities has been a focus of Western reporting on the use of DNA collection and genomics in mass surveillance, misuse of the technology is not limited to the Xinjiang region, Maya Wang, Human Rights Watch Asia Division associate director, said.

“That process of DNA collection goes far beyond what is necessary, proportionate, and lawful as required under international human rights law for data collection,” Wang told The China Project. “The DNA collection violates people’s basic human rights, and should be stopped. The whole DNA database should be discarded.”

Moreau agreed that U.S. policymakers should consider the human rights of Chinese citizens throughout the entire country — not just ethnic minorities — when formulating foreign policy.

“What about the other 1.3 billion people in China? Don’t they have a right to actually not be controlled via a combination of technologies?” he said. “That is really quite oppressive, and we can probably not stop it, but at least we can stop contributing to it.”

Representative Neal Dunn (R-FL) introduced similar legislation in the House of Representatives in August. Neither Dunn nor Senator Rubio responded to requests for comment. Promega, 10x Genomics, and Illumina didn’t respond to requests for comment, and Agilent and Thermo Fisher Scientific declined to comment.