This Week in China’s History: September 18, 1931

At 10:22 p.m., on September 18, 1931, World War II began.

That’s an oversimplification, needless to say. Any event as immense and complex as World War II does not start at a single moment. But if we are looking for a point in time, I’d put September 18 on the short list, along with September 1, 1939, July 7, 1937, or December 7, 1941 — and I’m inclined to go with 9/18 simply because it was first.

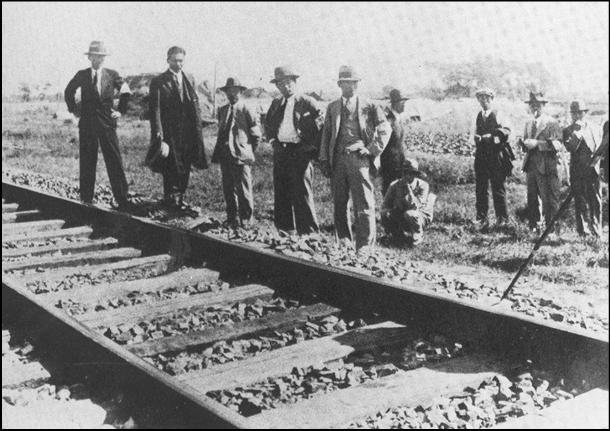

September 18 was the date that explosives detonated along the route of the South Manchurian Railway, near the city of Shenyang, typically called during that time by its Manchu name, Mukden. The explosion was small, damaging only about five feet of track: so minimal that a train passed along the route shortly after the blast with no problems. In fact, the most noteworthy aspect of the explosion itself might have been how little actual damage it caused (a result that, as we shall see, was not coincidental). The events of that Friday night are underwhelming, almost ridiculous, in the context of what they sparked.

Crucial to understanding the Mukden Incident and what happened next is the region’s geopolitical history. Manchuria — an area to the northeast of China and northwest of Korea, about the size of France and Germany combined — had long been the object of competing empires seeking its fertile open land and rich natural resources. The Russian empire had expanded eastward, jousting with the Qing since the early 17th century. A treaty first delineated their border in 1689, but in the 19th century, Russian pressure pried millions of acres along the Pacific Coast away from the Qing, and in the 1890s a Russian railway cut straight across Manchuria on its way to Vladivostok, a first piece of a planned occupation of Manchuria. Before long, a line extended south from Harbin to Changchun, with a branch running farther south to Port Arthur, at the tip of the Liaodong peninsula.

Japan came to the game much later, but — geographically closer and industrializing rapidly — it moved quickly. Japan went to war with China in 1894 and gained dominance over Korea (Japan took Korea formally as a colony in 1910) as well as (temporarily) control of southern Manchuria, plus economic concessions in the region. Competing Russian and Japanese interests led to war in 1904-05; Japan emerged as the dominant power in Manchuria, including taking control of the Russian-built railway south of Changchun. This trunk line ran down the center of Manchuria, connecting the region’s largest cities, and the company that owned and managed it — the South Manchurian Railway Company, or Mantetsu — had powers far beyond those of just a railroad company, taking on many functions of a government. (Demographic and sociological data collected by the Mantetsu remains an important source for historians studying this era.)

And although the Mantetsu in many ways acted like a government, the actual government struggled to maintain order. The Republic of China that replaced the Qing in 1912 claimed all of the Qing domains, including Manchuria, but Manchuria’s inclusion as part of China was not uncontroversial. Called Dongbei (“The Northeast”) in Chinese, the region was, almost by definition, beyond the Great Wall, and although parts of what is now Liaoning Province had been under Chinese control regularly, including under the Ming, regions farther east and north were not, and historically had few residents that could be considered Chinese in any meaningful way. (Underscoring the point, the Manchus, in an effort to preserve their ethnic identity and ancestral home, had forbidden Chinese immigration until the late 19th century.)

Qing policies became moot when the dynasty fell in 1911, and the republic that followed it struggled in its early years to integrate Manchuria into the rest of the country, a challenge exacerbated not only by Japanese and Russian encroachment, but also by internal division and weakness. Japanese influence increased steadily through a mixture of economic pressure, political intimidation, and violence.

Japan preferred to work through proxies, including the warlord Zhāng Zuòlín 张作霖 (the diminutive “tiger of Manchuria”), whom they expected to carry out their agenda. When Zhang proved too autonomous for Japanese desires, he was assassinated (not coincidentally, by a bomb planted along the railway, destroying his private train car), clearing the way for Japan to further expand its influence.

The Chinese republic looked to do the same. Each side faced a fundamental dilemma: The Republic of China was stumbling to establish new institutions and processes across a vast area — including the northeast — but retained formal sovereignty over the region. Japan was economically and militarily ascendant, but was viewed by the Chinese government as a hostile power. There was only so much Japan could do while at odds with the formal ruler of Manchuria.

The explosion that took place in September 1931 sought to change that dynamic. The railroad was under Japanese control, so the attack was seen as a move against Japanese interests; the Japanese army quickly assigned blame to Chinese terrorists. Within hours, Japanese troops stationed to protect the railroad line were mobilized against Chinese installations, and soon after a full-scale invasion of Manchuria was underway.

Of course, the bomb had not been planted by Chinese terrorists. It had not been planted by Chinese at all. The scheme was a false-flag operation directed by the Japanese Kwantung Army (the main Japanese military force in China): a pretext for the army to expand its influence into Manchuria. The fact that the bomb had caused so little damage was a feature, not a bug: The explosion was intentionally planned to not damage vital infrastructure — a bridge, for instance — that might require extensive repairs. Within a few months, the entire region was under Japanese control. In March, the independent state of Manchukuo was proclaimed, with the former Qing emperor Puyi as its chief executive (he would later be named emperor). The Japanese insisted the state was the product of local dissatisfaction with corrupt and ineffective Chinese rule. And while the internal dynamics of Manchukuo were more complex than the label “puppet” implies, the state existed primarily as an instrument of Japanese foreign policy.

The explosion and invasion caught not only the Chinese government but also the Japanese civilian government by surprise. Japan’s civilian and army leadership had clashed over how aggressively to pursue interests on the Asian mainland, and when the government refused to endorse plans to attack China, the army decided to present the government with a fait accompli. (The Japanese government soon fell, in part because of what had happened in Manchuria.)

China’s government responded to the attack by withdrawing. Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石 Jiǎng Jièshí) felt — correctly, almost certainly — that his forces would be unable to stop the Japanese advance, and so ordered his commander in the region, Zhāng Xuéliáng 张学良 (the son of Zhang Zuolin), to trade land for time. The withdrawal outraged many Chinese, and provided fuel for Chinese communists, who pointed to Chiang’s retreat as evidence of his weakness against outside invaders. While Zhang’s troops withdrew, Chiang took his case to the international community, protesting to the League of Nations that Japan’s invasion was illegal. The League’s Lytton Commission declared a year after the incident — with a remarkable amount of “both-sidesism” — that Japan was the aggressor. In response, Japan withdrew from the League in anger and Manchukuo remained in place until the end of World War II in 1945.

Today, 9/18 is marked in China as an embarrassing cautionary tale about the consequences of national weakness — and as a useful piece of anti-Japanese propaganda when it suits the Party’s needs.

This Week in China’s History is a weekly column.