This is book No. 38 on Paul French’s Ultimate China Bookshelf.

Blurbs:

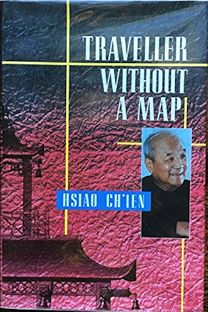

“Presents the life and times of one of China’s foremost men of letters with a richness of detail and liveliness of style that significantly extends our knowledge and appreciation of Hsiao Ch’ien as journalist, novelist, and translator. At the same time, the work deepens our understanding of the dilemmas facing China’s intellectuals during much of the twentieth century. Hsiao writes with grace and eloquence, leavening his serious tone with a pungent wit, and Jeffrey C. Kinkley has translated Hsiao with remarkable skill and sensitivity.”

—Carolyn Wakeman, University of California, Berkeley

“Politics is ever-present, but each page swarms with other things: accounts of the books Hsiao read, the conversations he had, the jokes he told, the wine he savored, the smell of blossoms in Cambridge of Heidelburg, and, above all, the way in which this man of enormous humor and endless curiosity perceives both East and West.”

—Sunday Times (London)

About the author

Hsiao Ch’ien (1910-1999), known to Chinese wartime newspaper readers as “Ruping,” was born Xiāo Bǐngqián 萧秉乾 in a Beijing slum to a family of Mongolian origin. He is now better known as Xiāo Qián 萧乾. Orphaned at 10 and imprisoned for political demonstrations when only 15, he was expelled from school, then became a teacher and translator while moonlighting in a publishing house. Working as a journalist, he lived for a time in London (on the same Hampstead street as our Book No. 29 author, Chiang Yee) and Cambridge, where he got to know many big beasts of the English literary and Sinological world — Arthur Waley, EM Forster, and Kinglsey Martin. He was arguably the only Chinese foreign correspondent in Europe during World War II, broadcasting on the BBC and later traveling with the U.S. Seventh Army after D-Day through France and Germany. His books include a novel of the wartime Burma Road (with illustrations by Chiang Yee), Etching of a Tormented Age (a short study of Chinese vernacular literature much admired by George Orwell, who became his friend in London and at the BBC), and the post-revolutionary How the Tillers Win Back Their Land (1951). Persecuted during the Cultural Revolution, he tried to commit suicide. In 1979, he attended the International Writing Program at the University of Iowa. He died in 1999 in Beijing.

The book in 150 words:

Traveller Without a Map (translated by Jeffrey C Kinkley) is Xiao Qian’s memoir, beginning with his hardscrabble origin in Beijing in the early years of the Chinese Republic, through his education, journalism training (under Edgar Snow), and work as a fiction writer and translator (his translations from English into Chinese include Shakespeare, Fielding, Ibsen, and others). Qian writes about life as a foreign correspondent, then discusses his decision, unlike many of his contemporaries in London and elsewhere, to return to the People’s Republic rather than stay abroad or go to Taiwan. This period, from 1949 onwards until his death, was difficult and often extremely harsh.

Your free takeaways:

My mother was a meek woman. My earliest memories are of her and my spinster cousin taking in sewing and laundry. Sometimes they sewed for the army supplies depots. Piles of unfinished and finished uniforms and cotton wool for padding always lined our kang, the two women were seldom without needles in their hands. As I grew older I used to accompany them when they went to get new work and drop off the old. This is how my mother supported me before she went out to work — this and selling off what little remained of her dowry.

Edgar Snow’s excellence as a reporter lay in his dissatisfaction with official reports and surface statistics. He saw through to the real essence of things, to the mind and the will of the people. He knew what they were for and what they were against.

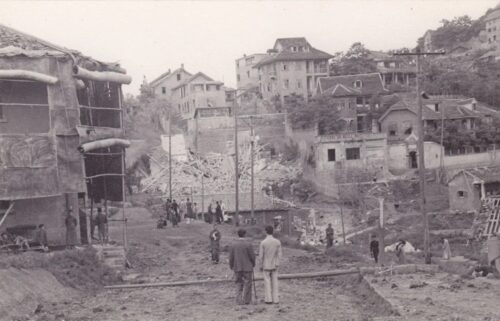

The months of that bombing were my most productive period of work for my paper, the Chungking Dagongbao. I sent despatches nearly ever week, some of them so long they had to be serialised. Every morning I, too, would climb up out of the tube and carry my bedding home. Then, stepping on pieces of broken glass and climbing over severed pipes, I would gather material for my report on London after the night’s bombing.

Post-war Berlin reminded me of Tianjin. When I had been there in early 1935, you could be in the Japanese concession one minute and the French concession the next. Now Berlin was much the same. You could walk a mile and come to a white billboard reading “You are leaving the American Zone.”

Why this book should be on your China bookshelf:

Xiao Qian’s memoir of his life, both in China and extensively overseas, is somewhat different to our two previous books written by overseas Chinese — Wu Ting-fang’s American memoirs from 1914 and Chiang Yee’s appreciation of 1930s London — in that Xiao Qian returned to China and lived in the People’s Republic (admittedly Chiang did for a brief period but was never intending to settle) and, despite persecution in the Cultural Revolution, was broadly supportive of the revolution.

Others who lived abroad did also return — Xiao Qian knew the poet Lù Jīngqīng 陆晶清 in London, who returned during the war and stayed afterwards, as well as the noted translators Wang Xianyi and his English wife Gladys Yang — but Xiao Qian is perhaps the most frank about those turbulent years in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, where he was purged, treated terribly, “sent down,” imprisoned, and later rehabilitated. Of course, part of the reason for the poor treatment of Xiao Qian was his years living abroad and the distrust that later came to coalesce around anyone with foreign experience.

Where Wu Ting-fang sees the West through the eyes of a Qing Dynasty diplomat, and Chiang Yee, approximately a decade older than Xiao Qian, through the eyes of someone more intimately acquainted with the early Nationalist period, Xiao emerges into political consciousness in a China with a highly active and growing left wing. This experience is built on at Yenching University (which he calls Yanjing), his trips to France, Britain, and Hong Kong before his return to China in 1949. In other words, Xiao Qian really speaks for a generation distinct from either Wu or Chiang, both in his reactions to the outside world and his core beliefs about the future of China.

Reading Xiao Qian’s impressions of a blitzed London, a divided Berlin, and the destruction of French villages, he was sympathetic to the need to rebuild while also seeing the “advances” of socialism in the British Labor Government of 1945, the heroism of the Soviet Union in the war, and the turn to the left everywhere, from Eastern Europe to Greece.

We should also note that Xiao Qian’s reflections and experiences in Britain and Europe in World War II are unique. He experiences both the civilian and military war, and his view of the British in particular — admiring their resilience against the Nazis while not ignoring negative traits in the society — is a good addition to the lighter-weight and more charming writing of his friend Chiang Yee.

Next time:

While a journalism student in Beijing, Xiao Chen helped out his teacher and fellow writer, an American called Edgar Snow — then living in the city and teaching at Yenching. Snow was working on a book that intrigued Xiao Qian, which looked at the communists living off in the caves of Yan’an. By the end of the Second World War, the world had been introduced to the name of Máo Zédōng 毛泽东, and for those outside China, this was largely because of the work of one man, Edgar Snow, and a book that remains widely read both in China and outside…