This is book No. 39 on Paul French’s Ultimate China Bookshelf.

Blurbs:

“An important book for anyone interested in the Far East, of course for anyone concerned in the spread of Communism. Essential for public libraries and college libraries.”

—Kirkus

“Edgar Snow was the first correspondent to penetrate into the heart of Communist China and to return to tell the tale. His book, planned and executed with meticulous care, is the most superb piece of reporting that I have ever read. It is the authentic, inside story of the Chinese Communists and of their relation to the Sino-Japanese War. The Communists and the war are more intimately connected than most people suppose.”

—The Atlantic

“He was the first foreign journalist to risk this trek to the forbidden Communist state in China’s West in the second half of the 1930s, when it was under heavy blockade by the Nationalist government. Snow invested a lot of time and energy in bringing an untold story out into the world…There is also much that is troubling about the book, especially Snow’s unquestioning, even adulatory, response to Mao’s story about the Communist past and present.”

—Julia Lovell, Five Books

“A journalistic scoop in 1937, this book has since become a historical classic. Snow’s sympathetic portrayal of the Chinese communists is somewhat naive, however, and it exposed him to widespread criticism during the McCarthy years.”

—Foreign Affairs

About the author:

Edgar Snow (1905-1972) is by far best remembered for Red Star Over China. However, his earlier life was also one of some adventure and excitement. From Kansas City, he attended the University of Missouri and looked set for a career in Manhattan in advertising — until the Wall Street Crash. The Depression set him off for China in the hope of more opportunity — he was to stay 13 years, know just about everyone, Chinese or foreign, who was anyone, and marry Helen Foster, another American journalist working in China.

He spent time in the famine districts of northwest China, traveled the Burma Road, and explored Manchuria. Living in Shanghai initially, the couple moved to Beijing, where Snow taught journalism at Yenching University and started several left-wing magazines. In this way, they became acquainted with leftist students who eased Snow’s path to Yan’an.

After World War Two, Snow continued to write about China and Asia, invariably from a leftist perspective. In the 1950s, he encountered some trouble from Senator Joseph McCarthy and eventually moved to Switzerland. He returned to China in 1960 and 1964 to interview Máo Zédōng 毛泽东 and Zhōu Ēnlái 周恩来. In 1970, he stood next to Mao during the National Day parade in Beijing, during which Mao told Snow that he would welcome Nixon to China. Snow never saw that trip, dying the day Nixon arrived in China.

The book in 150 words:

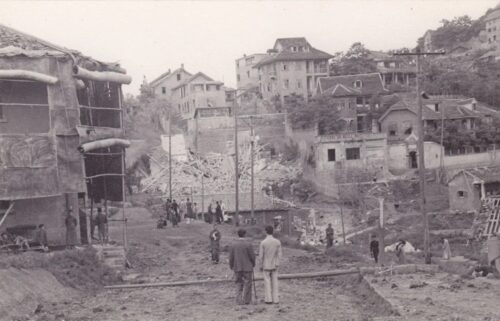

Edgar Snow made his way through Nationalist lines to Shanxi Province in June 1936, encountering a band of communists newly emerged, exhausted and decimated, after their 6,000-mile Long March. Snow found them developing the distinctive brand of communism that was to govern China during the Maoist era. Many of the men Snow interviewed in 1936 were the first-generation leaders of Communist China, and in particular he is credited with introducing Mao Zedong to a Western audience. Indeed, the best-known section of the book is Mao’s autobiography as related to Snow, which remains lauded in the P.R.C.

Your free takeaways:

Communists, over whose heads hung the sentence of death, did not identify themselves as such in polite — or impolite — society. Even in the foreign concessions, Nanking kept a well-paid espionage system at work. It included, for example, such vigilantes as C Patrick Givens, former chief Red-chaser in the British police force of Shanghai’s International Settlement.

Do the Reds really imagine that China can defeat Japan’s mighty war-machine? I believe they do. What is the peculiar shape of logic on which they base their assumptions of triumph? It was one of dozens of questions I put to Mao Tse-tung. And his answer, which follows, is a stimulating if perhaps prophetic thing indeed, even though the orthodox military mind may find it technically fallacious.

At last, after two weeks of hacking and walking over the hills and plains of Kansu and Ninghsia, I came to Yu Wang Pao, a big walled town in southern Ninghsia, which was then the headquarters of the First Front Red Army — and of its commander-in-chief Peng Teh-huai.

Great benefits have undoubtedly accrued to the Chinese Reds from sharing the collective experience of the Russian Revolution, and from the leadership of the Comintern. But it is also true that the Comintern may be held responsible for serious reverses suffered by the Chinese Communists in the anguish of their growth.

Why this book should be on your China bookshelf:

The debate around Snow and Red Star Over China has been a long and divisive one among Sinologists, China Watchers, and the Chinese Communist Paty. The CCP still lionizes Snow, most Western scholars think Red Star well worth close reading, and some think he was a patsy for Mao’s propaganda. There’s no doubt that Snow’s visit to Yan’an was closely stage-managed by the Party and that he saw nothing of the intense factional in-fighting taking place within the senior ranks that would work itself out, sometimes in deadly ways, over the next 20 to 30 years. Still, there is no denying Snow’s skills as a writer (and the largely unacknowledged input of Helen Foster-Snow as his editor throughout the project), his vivid recreations of the scene at Yan’an, his depictions of the genuineness of many Party members in wanting to improve the situation in China, and the extreme circumstances — the Long March, suppression by the Nationalists, war with Japan — that have formed the CCP worldview that lingers still today in terms of a tendency to isolationism, inability to seriously criticize itself, and continual factional disputes and purging.

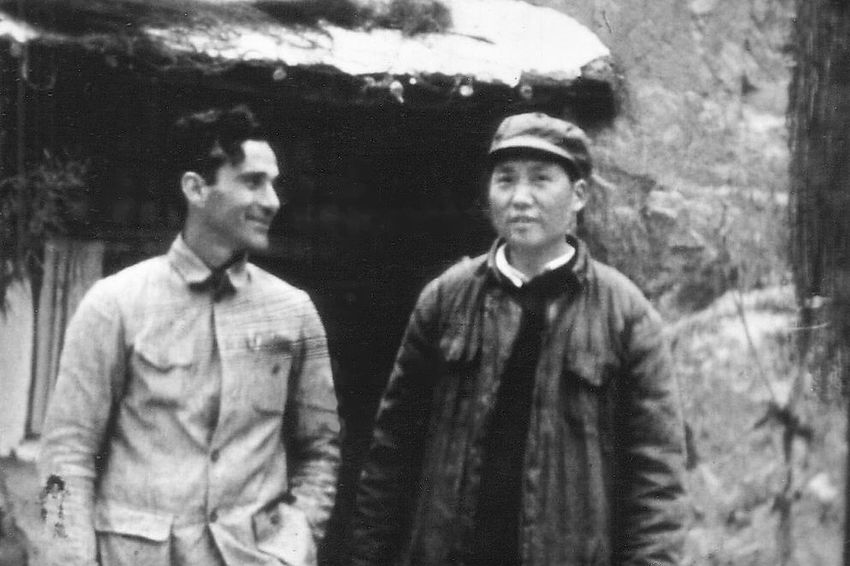

What most people now take from Red Star Over China is the autobiography of Mao, his life as told to Snow. Snow, of course, could only ask questions based on his ultimately limited knowledge of the Party. The same applies to his ability to judge any answers or claims made by Mao. It’s hard not to see an element of performance in Snow, donning the cap with the five-pointed red star for photos, etc. Snow was to be among the first of many foreign journos to play at revolutionary in Yan’an.

The photos included in Red Star Over China are also interesting. Any selection of images to accompany such a book must also be read as part of the argument of the text. They are important in that these early photos of Mao are really among the only ones we have from that time — more came later, but Snow captured a rawer Mao. Mao’s image has been subject to much manipulation, change, and various uses, so these early images are important.

The entire book was a massive coup for Snow. But what story does it tell of Mao at Yan’an? Perhaps not entirely the one Mao told Snow or that Snow understood Mao telling him. Biography, history, reportage are all famously tricky areas. But it’s also important to remember that the Nationalists clamped down on any publicity or reporting about Mao, Zhū Dé 朱德, and the communists, making Red Star Over China’s impact even greater.

Today, Red Star Over China is read differently in China, Japan, Europe, and the U.S., given prevailing attitudes to China, communism, socialism, and Snow himself. He is venerated in China, though perhaps now in the West a little forgotten, except of course by students of China who invariably find their way to him early on in their reading. That’s not a bad thing — Red Star Over China can at times be a gripping read, inspiring to would-be journalists perhaps. But it is also an abject lesson in the pitfalls of access in China, and a reminder to try to understand when you’re seeing the wider picture and when you’re being fed a line.

Finally, and perhaps most remarkably, it is important to remember that Mao spent a lot of time with Snow. They talked for hours. The chances of that sort of relationship being built between a foreign journalist and a senior leader of the CCP today is, quite frankly, unimaginable.

Next time:

A change of tack next week as we look at three books about sports in China and what modern China’s approach to sport, competition, and trying to establish world-class sportsmen and women, leagues, and teams tells us about the country’s development trajectory. First off, football (OK, soccer, if you must).