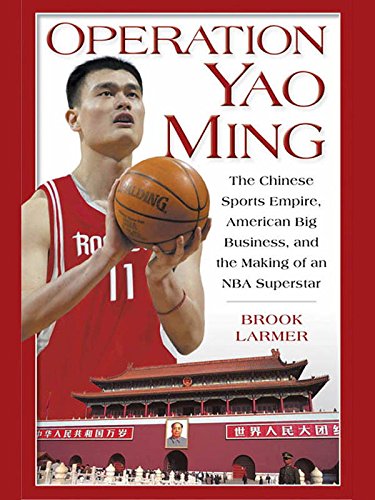

This is book No. 41 on Paul French’s Ultimate China Bookshelf.

Blurbs:

“The riveting story behind NBA giant Yao Ming, the ruthless Chinese sports machine that created him, and the East-West struggle over China’s most famous son.”

—Financial Times

“A Byzantine tale of sports, commerce and politics, nimbly shuffled by the astute journalist Larmer.”

—Kirkus

“Larmer, Newsweek’s former Shanghai bureau chief, crafts his narrative well, explaining the byzantine interests competing for their pound of Yao’s flesh with admirable simplicity. Yao’s story is so controlled that when he finally overcomes his initial clumsiness and starts rebelling against his government at book’s end, it’s hard not to feel empathy for the gentle giant.”

—Publishers Weekly

“Larmer is a former Newsweek bureau chief, and this is his first book. And make no mistake: This is serious, professional journalism. The research and reporting is absolutely relentless.”

—ESPN

About the author:

Brook Larmer, originally from the U.S., was the Newsweek bureau chief in Buenos Aires, Miami, Hong Kong, and Shanghai, where he lived while researching Operation Yao Ming. He is currently Bangkok-based and a contributing writer for The New York Times Magazine, National Geographic, and The Economist’s 1843 Magazine.

The book in 150 words:

In the early 2000s, the Shanghai-born basketball player Yáo Míng 姚明 was the most famous Chinese person on Earth. The 7-foot-6 Houston Rockets center was an NBA All-Star and multimillionaire, and the story in Chinese sports. But where did he come from? How did he rise to such prominence, emerging from the dying days of the Maoist sports program? How did his career progress through the Chinese basketball league with the PLA Bayi Rockets and then the Shanghai Sharks? Eventually, China’s sports machine collided with Western capitalism, with public opinion ebbing and flowing in its like and disdain for rich celebrities. Yao Ming was undoubtedly a symbol in China — but of what? And for who?

Your free takeaways:

A cloud of cigarette smoke hung over the basketball court, stubbornly resisting the gusts of wintry air blowing through the unheated gymnasium. It was December 1999, and few places on earth could have felt further removed from the glitzy world of the NBA than the home court of the People’s Liberation Army team, a dimly lit arena in the coastal Chinese city of Ningbo.

The marketing wizards of the NBA like to talk about China as basketball’s “final frontier.” But the Middle Kingdom’s fascination with hoops began long before Michael Jordan and the Chicago Bulls made their debut on Chinese television in the late 1980s.

Just ten days later Yao boarded a plane for the United States, where he would face one of the most public job auditions in sports history. The top coaches and executives from 26 of the 29 NBA teams – along with hundreds of media – were converging on Chicago to watch the little-known giant display his skills in a specially arranged predraft workout.

Even by the time Yao arrived in 2002, only a few American aficionados might have recognized the moon-faced actress Gong Li or then Chinese president Jiang Zemin in his bug-eyed glasses. Ask the average American to name a living person from mainland China and he would likely have drawn a blank. Almost by default, Yao would become the face of China.

Why this book should be on your China bookshelf:

It is perhaps not so easy to remember, or imagine (depending on your age), quite how massive and significant an impact the NBA’s spectacular push into China and the emergence of Yao Ming in the early 2000s was. Now it seems a routine part of Chinese life — NBA games, merchandise, player tours, etc. But while many Chinese had in the 1990s been able to access major European soccer — as we saw last time with Bamboo Goalposts — chosen their teams, bought the kit, seen many of those same teams play in China, basketball — though played in China for a century — was relatively new. Accompanying the NBA explosion and Yao Ming’s success was also a massive expansion of casual playing of the game, with more courts created, local leagues (often tied-in to sports brands), and a growth in general mass popularity. Even those not really interested in sports (including your author here) couldn’t fail to notice this social phenomenon.

Larmer’s book was, and is still (though perhaps in a more historical sense now), important, as it tracked this phenomena from both ends — the NBA and big sports brands excitedly, though sometimes warily, eyeing the potential China market, while the game emerged as a critical resource for the Chinese government along with other sports. People like me may have noticed the new hoops springing up in city parks, but the government was thinking medals, trophies, national glory. As the reviewer for Kirkus noted, “Unlike the wholesale revamping of the country’s economy, athletics provided a fast track to the global stage, raising China’s stature and projecting a sense of national ambition. As the rest of the country careened down the capitalist path, sports prodigies were viewed in the old Maoist way as state assets, destined to live and work for the glory of the motherland.”

And that dichotomy is best embodied in the character of Yao Ming — often seen as a passive individual seemingly not interested in his own trajectory, and at other times as a cunning and overreaching individualist. The government didn’t know how to handle him; neither did the Chinese media, and often also neither did the Chinese public.

Looking back now, we can also perhaps perceive this era, and maybe the sport of basketball itself, as a high point of P.R.C.-U.S. cultural relations. It is perhaps hard to imagine such a furor over a figure like Yao going to the States now.

Next time:

Basketball and soccer are of course games for the everyman — a ball, some space, and away you go. Champions can emerge from the playing fields and streets, fans are ordinary people, turn on any TV and a game is never far away. But there are other sports…sports that come with a little more obvious political and cultural baggage, too — bourgeois sports! So next time, a look at the game so many businesspeople wanted to play, that Zhū Róngjī 朱镕基 enjoyed, but that also potentially made you a suspect in anti-corruption crackdowns — good old golf.