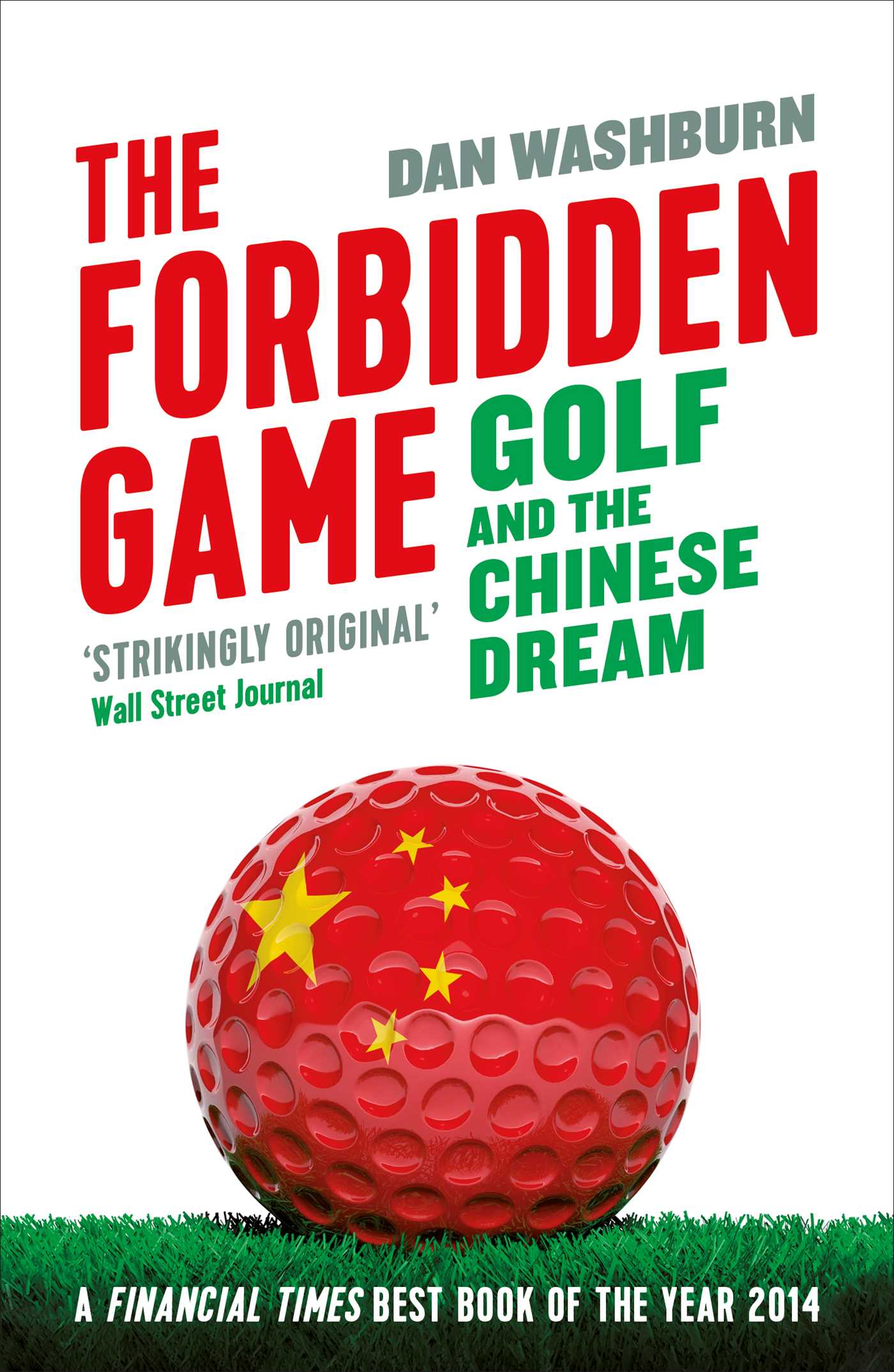

This is book No. 42 on Paul French’s Ultimate China Bookshelf.

Blurbs:

“From a bourgeois pastime denounced by the Communist Party of China, golf became the embodiment of the new Chinese dream. The Forbidden Game speaks volumes about how much this country has changed. You can learn more from this engaging, well-written book about golf than from weightier tomes that have tried to tackle China’s transformation. A hole-in-one from Dan Washburn.”

—Barbara Demick, author of Nothing to Envy

“I’m not a golfer or a Sinophile, but The Forbidden Game spoke to me. At its core, it is classic storytelling — underdog tales of struggle, perseverance and overcoming adversity. The men in this book may not be perfect, but they are real people you can root for. It’s like the quintessential American Dream story, only it’s set in China.”

—Brian Grazer, award-winning producer of television and film, including Best Picture Oscar winner A Beautiful Mind

“The Forbidden Game is an important and fascinating work. By taking us deep into China’s secret golf culture, Dan Washburn brings to life the contradictions and complications of this unique nation’s struggles with modernity — as well as an inspiring group of home-grown players who have paved the way for the rising generation of Chinese pros.”

—Sports Illustrated

“In his revealing and witty new book, Dan Washburn unearths a story that nobody knows: how the game that Chairman Mao denounced as the ‘sport for millionaires’ stirred the dreams of farmers and soldiers, tantalized foreign pioneers, and provoked a Chinese crackdown. This is a tale about golf no more than Seabiscuit is a story about horseracing…Vivid, surprising, and human.”

—Evan Osnos, The New Yorker

About the author:

Originally from the U.S., Dan Washburn lived and worked for many years in Shanghai as a freelance journalist. His writing appeared in the FT Weekend Magazine, The Atlantic, The Economist, ESPN, Foreign Policy, Golf Digest, Golf World, Slate, the South China Morning Post, and other publications. He is an award-winning reporter and managing editor. Additionally, his work has been featured in the anthologies Unsavory Elements: Stories of Foreigners on the Loose in China and Inside the Ropes: Sportswriters Get Their Game On. He was also the founding editor of Shanghaiist.com, at one time one of the most widely read English-language websites about China. He later returned to the United States to work for the Asia Society in New York.

The book in 150 words:

Denounced by Mao, undoubtedly bourgeois, a game for the privileged — how did golf ever get off the ground in China? Dan Washburn argues that the game is a barometer for all of China’s current concerns (at least in the earlier part of the 21st century) — economic growth, “social harmony,” corruption, the growing wealth gap, and, most absorbing, the hopes and aspirations of the few players from more humble roots. Washburn follows several characters, including an American golf course developer and Zhōu Xùnshū 周训书, who, though from a humble background, wants to be a golf pro.

Your free takeaways:

Golf, its emergence and growth in China, is a barometer for this change and the country’s rapid economic rise, but it is also symbolic of the less glamorous realities of a nation’s awkward and arduous evolution from developing to developed: corruption, environmental neglect, disputes over rural land rights, and an ever-widening gap between rich and poor. The game of golf, and the complex world that surrounds it, offers a unique window into today’s China, where new golf courses are at once both banned and booming. I knew little about the sensitivities surrounding golf in China when I first started covering tournaments there in 2005 for ESPN.

In the past decade China has been the only country in the world to experience what might be called a golf course boom. While the struggling global economy had courses shutting down elsewhere, they were opening by the hundreds in China. From 2005 to 2010, the number of Chinese courses tripled to more than six hundred. An impressive feat, especially when you consider that building new courses has been technically illegal in China since at least 2004.

This book is about three men — two born in China, and one who never thought he’d end up there — who find themselves, either by accident or fate, caught up in golf’s shift to the East. Wang had little choice but to accept the golf developers in his back yard; Martin is just trying to take advantage of the boom as long as he can. And, at the heart of it all, there’s Zhou, whose rise from peasant farmer to security guard to pro golfer is the stuff of movies.

Sometimes, the lack of experience building golf courses inspired Chinese developers to make strange requests. Martin recalled one owner who wanted to build a water-themed golf course. No golf carts. No cart paths. Golfers would travel from hole to hole by boat. Another owner wanted to build a villa right in the middle of a par-3 fairway. And then there was the guy who wanted a hole to be a giant funnel — anyone whose ball landed within thirty feet of the pin on this par-3 hole was guaranteed a hole-in-one. “Mini-golf on a professional golf course,” Martin sighed.

Why this book should be on your China bookshelf:

To be honest, you don’t hear much about golf in China these days — major tournaments still happen, the Volvo China Open, for instance, but it’s all a lot more lowkey than it used to be. Hong Kong businessmen still cross the border for a round at Mission Hills, golfing holidays to Hainan still happen, but it’s a little quieter than previously. Rewind to the earlier 2000s, and you get a different picture — golf was a big thing! But then, so was aspiration.

Putting your head above the parapet was common — Zhū Róngjī 朱镕基 played golf! — but in more recent, more abstemious times, golf has become almost underground again. The cards are stacked against it in a way they’re not for more everyman sports like soccer and basketball, or places where China feels it can make an impact (think, until recent scandals, snooker). Golf is a game that still retains an aura of corruption, and is still overwhelmingly a rich man’s sport — there are not really any low-cost public courses in China. The image of dodgy deals and corrupt handshakes out on the greens is still commonplace, and appears in patriotic TV cop shows regularly.

So Washburn’s book — a little like Rowan Simons’s on soccer and Brook Larmer’s on basketball — is now essentially an historic document. It reflects a time that may seem almost unimaginable to anyone under 30 — a time when senior leaders and foreign businessmen hacked away while being followed by caddies, doing tech transfers and negotiating billion-dollar inward investments. To take to the course now — for the country’s political leaders at least — would be to abdicate a leadership position, probably come under some suspicion, and destroy your career.

And the other question is whether the Chinese public has any interest in golf these days. There are, I think, quite few, if any, Zhou Xunshu’s around now. Chinese male pro golfers have not managed to attain significant international status, and none have broken out of the sports inner circle to become a household name the way Yáo Míng 姚明 did in the NBA.

Of course, there are some that claim China invented golf (the Scots do not agree!). Even if that is true, it’s not a game that, right now at least, seems to have captured the public’s imagination over there. So we have Dan Washburn’s Forbidden Game as a testament to an earlier time — of openness, aspiration, international curiosity, and when every township cadre wanted a golf course the way everyone wants a Red Tourism destination these days.

Next time:

Time once more for a change of tack: three classic modern Chinese novels by the country’s biggest literary beasts that remain widely read, taught, and studied. We start with perhaps China’s most accessible and engaging author and his tale of the iniquities and degradations of Beijing’s commonplace rickshaw pullers.