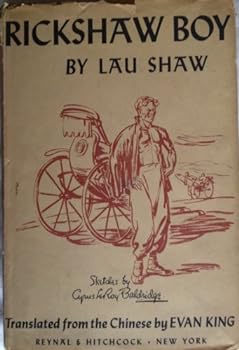

This is book No. 43 on Paul French’s Ultimate China Bookshelf.

Blurbs:

“Lao She’s greatest novel.”

—The New York Times

“An impressive novel of an individual struggling against and defeated by a corrupt society.”

—Library Journal

“Rickshaw Boy is a Chinese story and a successful portal into 1930s China. But it’s also a universal story of the hopelessness that extreme economic disparity breeds; this is a very relevant message in our world today.”

—1001 Book Reviews

“This novel marks the peak of Lao She’s career as a professional writer and registers a new approach to the representation of China in its absurdist situation. It can be read as an ‘epic’ of modern China.”

—Barnes and Noble Review

About the author:

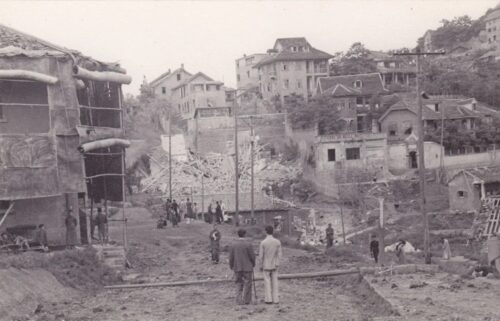

Lǎo Shě 老舍 (1899–1966), a.k.a. Shū Qìngchūn 舒慶春, was born in Beijing to a Manchu family. His father died fighting the foreign invasion of Beijing in 1900 in the wake of the Boxer Uprising. In 1913, he was admitted to Beijing Normal Third High School and then Beijing Normal University, graduating in 1918. He spent time as a teacher in Beijing and participated in the May Fourth cultural movement. Then there was four years in London in the 1920s teaching at the institute that would become the University of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS). Here, he was exposed to British literature and early modernism, both of which influenced his writing style. In 1929, he left Britain for Singapore, returning to China a year later and teaching at various universities.

After the Japanese attack on China, he became a founder of the National Resistance Association of Literary and Art Workers with Máo Dùn 茅盾 and Bā Jīn 巴金, among others. In 1946, he traveled to the United States, where his friend (and a translator of Rickshaw Boy) Pearl S. Buck suggested he stay after the 1949 revolution. However, he returned and continued to write in Beijing.

Lao She experienced beatings and other mistreatment during the Cultural Revolution, which pushed him to commit suicide by drowning in Beijing’s Taiping Lake in August 1966.

The book in 150 words:

Lao She’s classic (and eighth) novel, Rickshaw Boy (a.k.a. Lo-t’o Hsiang Tzu, a.k.a. Camel Xiangzi), is about the hardscrabble life of a Beijing rickshaw puller. Published in installments in the magazine Cosmic Wind (Yuzhou Feng) beginning in January 1937, it has since become a classic of Chinese literature. The novel is centered on a young country boy come to the capital to be a rickshaw puller, “Camel” Xiangzi. Though at the bottom of society, he hopes to improve his social status and get rich through working hard. But this is impossible, as the system is rigged against him.

Your free takeaways:

The rickshaw men in Peking form several groups. Those who are young and strong and springy of leg rent good-looking rickshaws and work all day. They take their rickshaws out when they feel like it and quit when they feel like it. They specialize in waiting for a customer who wants a fast trip. They might get a dollar or two just like that if it’s a good job.

The life of a poor man…was like the pit of a date, pointed on both ends and round in the middle. You’re lucky to get through childhood without dying of hunger, and can hardly avoid starving to death when you’re old. Only during your middle years, when you’re strong and unafraid of either hunger or hard work, can you live like a human being.

Sloth is the natural result of unrewarded hard work among the poor, reason enough for them to be prickly. Experience had taught him that tomorrow was but an extension of today, a continuation of the current wrongs and abuses.

He tried to get passengers twice. No one hired him. That glum feeling came back. He didn’t want to think about it but his mind was so congested and confused he just had to get things cleared up. This affair seemed to be totally unlike other problems…there was nothing he could do about himself, about the present or the future. It was as if he were a little insect caught in a spider’s web trying to break free and never succeeding.

Why this book should be on your China bookshelf:

Come for the vivid and rich description of old Peking, stay for the gripping story of the life of Camel Xiangzi, and leave with a deep impression of the relentless and hard life of a rickshaw puller in a corrupt society. It’s a searing indictment of exploitation and the degradation of labor in Republican-era China.

This novel is the greatest work of what would become known as “proletarian literature” (perhaps along with Mao Dun’s Midnight, book No. 9 on the Ultimate China Bookshelf). It wasn’t written by a leading light of the League of Left-Wing Writers — not Lǔ Xùn 魯迅, nor any of the proponents of socialist realist literature such as Dīng Líng 丁玲, Hú Fēng 胡风, or Méi Zhì 梅志 — but instead by a man who was inspired during his London sojourn in the 1920s to emulate Dickens (in his books The Philosophy of Lao Zhang and Mr. Ma and Son), proto-science fiction (Cat Country — a book we may return to in the future), and the saga (Teahouse). In this sense, Rickshaw Boy is an outlier in Lao She’s oeuvre.

Camel Xiangzi is a stereotype of a social phenomenon that seems to be a constant in Chinese history — the peasant, often gullible but honest, migrating to the city, turning into an urban tramp (almost like Chaplin’s Little Tramp), and experiencing the vicissitudes of urban life and the Chinese capitalist system of the time. The storyline could be (and has been) repeated many times with modern migrant worker tales. It became a 1982 film, and a bowdlerized version appeared that changed the ending to a happy one. Those who have seen both the bleak and realistic original and the censored (with a happy ending) versions of director and writer Lǐ Ruìjùn’s 李睿珺 2022 film, Return to Dust — which tells the story of Ma Youtie, an impoverished and exploited peasant, and his disabled and incontinent wife — will know this process continues today.

Alongside the idea of Rickshaw Boy as China’s preeminent example of proletarian literature (though not Party literature, as there is no well-meaning cadre to save Camel Xiangzi and lead him to a political redemption) is the notion of the novel as a supreme example of Lao She’s desire to elevate baihua, or plain everyday language, to one fit for literature alongside classical Chinese. Lao She was an early user of baihua, and Rickshaw Boy is arguably one of the prime examples of its establishment as the literary norm in China.

And let’s not forget that, social commentary and baihua usage aside, Rickshaw Boy features some masterful set pieces — crowd scenes, the intensity of the community of rickshaw pullers, the exhausting life of the puller.

Next time:

Lao She remains a much-loved Chinese writer and a “Big Beast” in China’s literary world, but next time, perhaps a writer of even greater veneration and stature needs to be added to our expanding shelf…