On China’s World Cup and Summer Olympics hosting ambitions

The China Sports Column is a The China Project weekly feature in which China Sports Insider Mark Dreyer looks at the week that was in the China sports world.

A couple of stories emerged this week, with either having the potential to dramatically change the face of China’s sporting landscape.

First, the South China Morning Post claimed that China will submit a bid for the 2030 FIFA World Cup (with a source saying “the 2030 bid would likely be a test run ahead of China bidding for and expecting to win the right to host the 2034 World Cup”). Then, the city of Shanghai confirmed it was looking into a bid for the 2032 Summer Olympics.

Let’s start with the World Cup. There has been serious talk of China hosting one for most of this decade — with many observers feeling it’s simply a question of when, not if — and so the story immediately feels more believable, even if the paper’s single source remains anonymous.

However, what the SCMP story neglects to point out is that China can’t actually submit a bid for the 2030 tournament under current FIFA rules, because Qatar — a team, like China, from the Asian Football Confederation (AFC) — will host the 2022 edition, meaning that AFC teams cannot bid again until 2034.

Technically, if no suitable bid is made from any of the federations who are able to bid for 2030, then FIFA can decide to open it up the rest, including China.

But there’s simply no way that will happen.

Multiple countries have already expressed an interest, with two bids in particular looking extremely competitive.

A joint bid — something that FIFA President Gianni Infantino has encouraged in recent times — from Argentina, Uruguay, and Paraguay has in its favor both past success (two World Cup wins for each of Uruguay and Argentina) and sentiment, as 2030 would mark 100 years since the very first World Cup, held in Uruguay.

Meanwhile, UEFA President Aleksander Ceferin had initially declared that 2030 would be “Europe’s time” to host once again, and has now appeared to give his backing to a UK-wide tournament.

Those both look like fearsome bids, with Morocco — beaten out by the U.S./Canada/Mexico trifecta for 2026 — also set to bid again, this time alongside Tunisia and Algeria.

That doesn’t exactly leave the door wide open for China to sail into the bidding process at the second stage, once all the initial bids are rejected.

But the Chinese don’t necessarily see it that way.

More than one person at the CFA has mentioned to me that they think there could be a certain amount of flexibility in the rules — which, notably, have changed before — and it’s true that the latest draft of the World Cup bidding regulations was designed specifically for the 2026 tournament, rather than for all future editions.

However, FIFA remains a Western organization despite a growing list of Chinese sponsors, and it would take something dramatic for that to change before the 2030 bidding process is opened.

As for the 2030 bid being a test run for 2034 — it’s not hard to see where this line of thought originated: the Olympics.

China first bid for the 2000 Olympics, which ended up going to Sydney, and used that experience to strengthen its ultimately successful bid for 2008. On the winter side, China attempted to do the same thing — test the waters for 2022, before really going for it in 2026 — but the competition for 2022 kept dropping like flies, meaning that the Winter Olympics will arrive in China sooner than the hosts had originally anticipated.

We don’t expect anything similar happening with the World Cup.

At any rate, if China isn’t allowed to submit a bid for 2030, it won’t be getting much experience for 2034. And if sentimentality wins out and the South Americans get their centennial celebration in 2030, any European bid would then be hugely favored four years later.

Which is why, perhaps, China is trying to double its chances of landing a major sporting tournament by looking at the Olympics. City officials in Shanghai confirmed this week that they have ordered a feasibility study on hosting the 2032 Olympic Games.

Understandably, the media got pretty excited, prompting officials to pump the brakes a little and stress that no decision has yet been made as to whether a bid would even be launched.

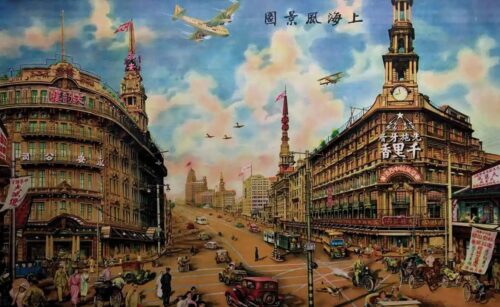

But it would be staggering if Shanghai didn’t now throw its hat in the ring given that the city has already stated it seeks to become a world-class sports city.

What better way to do that than host the biggest sporting prize of all among competing metropolises? While a World Cup is spread across one or more countries, the vast majority of a Summer Olympics is focused on one place, making that global spotlight even more focused.

Some have argued that Shanghai’s bid could be scuppered by the country’s parallel World Cup plans, but Rio’s Olympic credentials were only burnished by a successful World Cup two years beforehand.

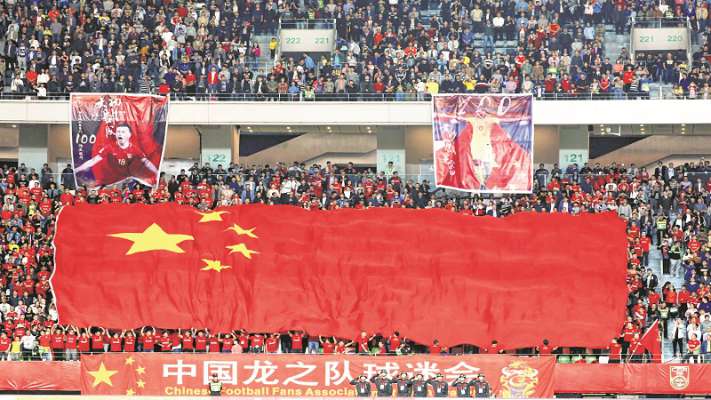

The one area that China needs to seriously consider for both of these two events, though, is how it can reconcile its desire to host large, fun events with a severe dislike of crowds.

Restrictions were certainly present when Beijing hosted the 2008 Olympics, but things seem to have become much tighter in the ensuing decade.

As shown by last week’s fiasco when fans in Shanghai were effectively prevented from seeing their team win the title, it defeats the stated purpose of trying to develop a sports industry if security and social order are prioritized at the exclusion of everything else.

Shanghai SIPG clinches club’s first league title — in half-empty stadium, because Chinese football

Other countries manage to find a way to make entertainment events both fun and safe. Unfortunately, that still remains a novel concept in China.

The China Sports Column runs every Friday on The China Project. Follow Mark Dreyer @DreyerChina.