China Year-in-Review, 2018: The Great Recalculation

The Red Paper is The China Project’s guide to the trends and stories that mattered most in 2018, and an outlook for business, politics, culture, and society in 2019.

Below is a preview of the Red Paper. Click here to purchase the full 60-page report.

The Great Recalculation

By Jeremy Goldkorn, The China Project editor-in-chief

Trade friction (贸易摩擦 màoyì mócā) is one of the Chinese “words of the year” of 2018 as selected by a government language research organization, and it is appropriate. But it does not go quite far enough — if I had to choose a word of the year for China, it would be recalculation (重算 chóngsuàn).

The year 2018 was the start of a time of reconsideration for China and the countries it deals with. This year, many old certainties and conventions crumbled. It was the 40th anniversary of China’s reform and opening up, but future historians may choose 2018 as the final year of that era.

The year 2018 began with optimism among many in technology and venture capital. Artificial intelligence (AI), fintech, on-demand bicycles, a few major initial public offerings (IPOs), and the awesome power of China’s internet giants like Tencent and Alibaba — these were the subjects of excited conversations among investors on both sides of the Pacific.

But the last half of the year has been less bubbly: There is talk of a “venture capital winter,” shares of the major internet companies are down, and in December, there were reports of significant layoffs at several listed tech firms.

China’s pharma and healthcare companies thrived in 2018. As the government streamlined approval processes for new cancer treatments and other drugs, pharma companies have raced ahead with clinical trials, and investors have placed large bets on healthcare services, genetics, and other hi-tech life sciences.

However, serious problems continue to plague the healthcare sector: This year saw continued patient-on-doctor violence at hospitals; one company manufactured large batches of substandard vaccines; and another produced a blood pressure drug for international distribution that contained carcinogens. Moreover, scientists around the world were appalled by an experiment that reportedly led to the birth of two gene-edited babies.

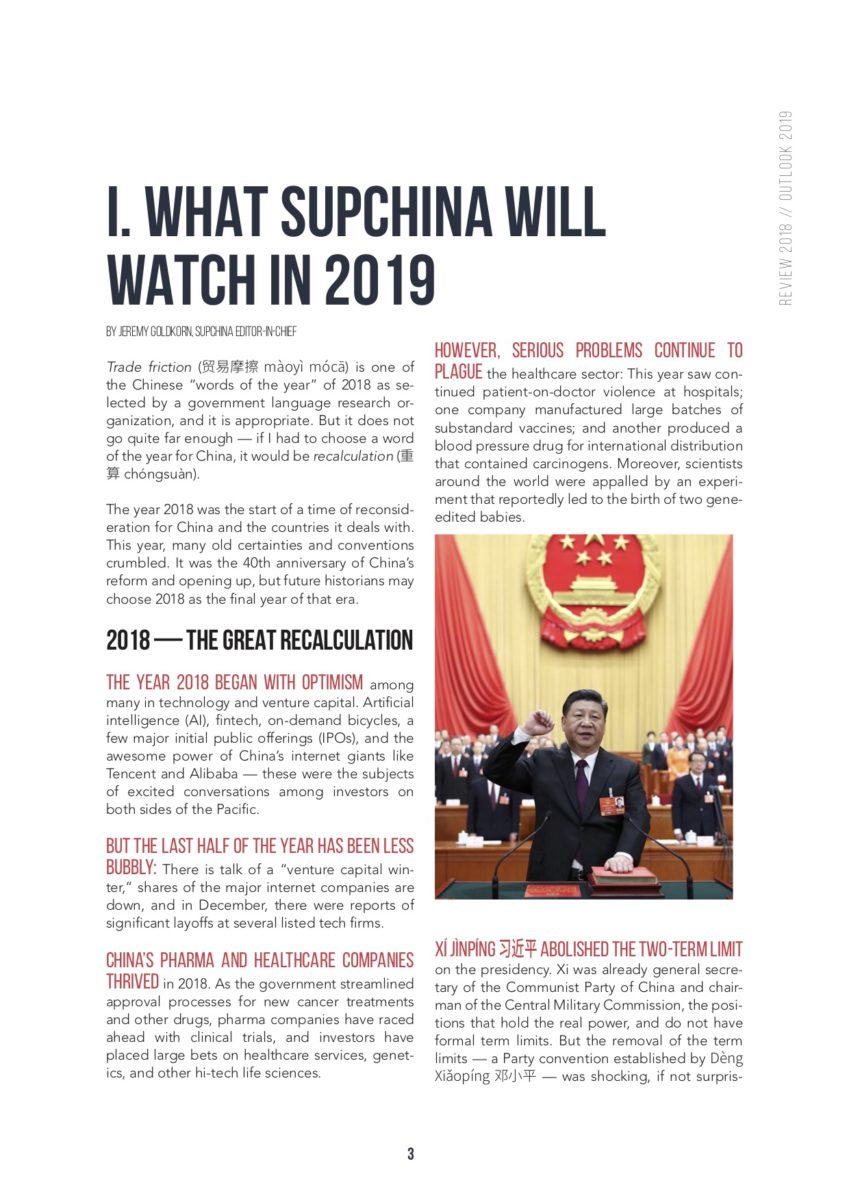

Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 abolished the two-term limit on the presidency. Xi was already general secretary of the Communist Party of China and chairman of the Central Military Commission, the positions that hold the real power, and do not have formal term limits. But the removal of the term limits — a Party convention established by Dèng Xiǎopíng 邓小平 — was shocking, if not surprising. Signs have been there since Xi became general secretary of the Party. This year, rule by consensus — which characterized Party leadership in the first 40 years of reform and opening up — died on the 40th anniversary of those reforms.

Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 abolished the two-term limit on the presidency. Xi was already general secretary of the Communist Party of China and chairman of the Central Military Commission, the positions that hold the real power, and do not have formal term limits. But the removal of the term limits — a Party convention established by Dèng Xiǎopíng 邓小平 — was shocking, if not surprising. Signs have been there since Xi became general secretary of the Party. This year, rule by consensus — which characterized Party leadership in the first 40 years of reform and opening up — died on the 40th anniversary of those reforms.

The Trump administration declared “competition” with China as its policy going forward. There is bipartisan consensus in the U.S. about the need to get tough on China, and support from many business leaders, even if no one agrees what exactly should be done. Despite the American president alienating many allies, concern about China’s rise is growing in European capitals and in the other members of the “Five Eyes” — Australia, Canada, the U.K., and New Zealand.

Scholars, journalists, and politicians in Australia and New Zealand, as well as in the U.S. raised the alarm about Chinese Communist Party “influence operations” and espionage. These worries are spreading to Europe and beyond: Beijing angrily denied reports early in 2018 that it had bugged the new headquarters of the African Union in Ethiopia which Beijing funded to the tune of $200 million.

In many countries in Africa and on China’s Belt and Road, including Sri Lanka, Malaysia, and the Maldives, civil society actors and leaders spoke out against Chinese projects they say leave host countries saddled with debt, and complained of other exploitative behavior.

A vast system of surveillance and internment camps in Xinjiang was documented, with compelling evidence, by journalists and scholars in 2018. Elsewhere in China, the repressive nature of Xi’s China was impossible to ignore, even by those most sympathetic to Beijing. Barely a week went by in 2018 without news of activists being locked up, teachers being silenced, or churches and mosques being demolished.

A vast system of surveillance and internment camps in Xinjiang was documented, with compelling evidence, by journalists and scholars in 2018. Elsewhere in China, the repressive nature of Xi’s China was impossible to ignore, even by those most sympathetic to Beijing. Barely a week went by in 2018 without news of activists being locked up, teachers being silenced, or churches and mosques being demolished.

Hong Kong’s lack of autonomy from Beijing became impossible to deny this year, as the Special Administrative Region’s government expelled a foreign journalist, jailed activists, and banned a political party for advocating independence.

#MeToo’s vitality in China was surprising, given how effectively the government has crushed other activist movements. Also noteworthy this year was the emergence of a well-organized network of student Marxists at elite universities collaborating with factory workers on labor rights.

Taiwan held local elections — think midterms — in November. Voters essentially repainted the map of Taiwan blue from green, or from ruling party Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), which is broadly pro-independence, to the more China-friendly Nationalist Party (KMT). Throughout the year, China has snarled at Taiwan in various ways, signaling Beijing’s unhappiness with the DPP and President Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文 Cài Yīngwén).

North Korean missile tests and Donald Trump’s reaction to them alarmed the world at the beginning of the year. But the anxiety ended after the Singapore Summit in June — when Trump effectively folded and ended his “maximum pressure” strategy, and China re-embraced North Korea. The DPRK has not conducted further missile tests, but reports suggest that there has been no reduction in its capacity to build missiles.

China opened its financial sector to foreign participation a little more this year. There is growing interest in domestic shares, government bonds, and corporations assuming majority stakes of financial firms, but many observers remain skeptical about Beijing’s commitment to giving foreign firms a level playing field.

The Red Paper is available for purchase on our The China Project Shop for $48.88, OR included for free with the purchase of a The China Project Access subscription — from now until January 14, get a year’s subscription at 25% off for just $66, for a total value of over 52% off!

To make a group purchase of the Red Paper for corporate or teaching use, please contact sales@thechinaproject.com.