“Most foreigners’ photos, they come from some exoticizing angle, or they're standing from the point of view of the conqueror. They are really attentive to our beggars, our poor people…But for a Chinese photographer, we would focus on beauties and dignities.”

You may know Tóng Bīngxuě 仝冰雪 from his Twitter account. His historical yet timely photos often reveal stories of a bygone China, far from modern reference points. Drawing from archives and his personal collection, Tong’s images are unusually well-preserved, sometimes tongue-in-cheek. Take a look at this clever series of photos on preparing Peking duck, for instance…

Part one:

Photo history of Beijing Roasted Duck, by Mark Kauffman, 1947. pic.twitter.com/aNRGmLIMIJ

— China in Pictures (@tongbingxue) January 19, 2019

…from 1947!

Twitter, however, is just a fun way for Tong to share his passion for photos with the non-Chinese-speaking world. His real work happens offline. For nearly two decades, Tong has collected old photographs of China, becoming in the process a historian and curator. His one-time hobby has led him to bring carefully-curated exhibits to museums and galleries all over the world. One of his best-known projects, featuring a collection about a man who took a self-portrait every year over the course of 62 years, has been exhibited in Korea, Brussels, and the U.S., to name just a few. Tong’s pursuit of old photographs has also led him to write a book about the early history of photography in China, and has contributed to a growing sense of appreciation within the country for the value of this particular form.

Tong recently sat down with The China Project to talk about his experiences, from his first photo purchase of 50 yuan in 2000 to hosting exhibitions in Europe, and what he’s learned over the years.

The China Project: How did you get started collecting photos?

Tong Bingxue: In the year 2000, I bought an apartment, and in my head I was thinking, after renovating this place, what should I hang on the walls? Because I didn’t want to just hang some decorative ornaments, some fake things. So, then I went everywhere to look for something different and I ended up in Panjiayuan (an antiques/flea market in Beijing) and bought that picture of a transit waystation from Shanxi. (The picture shows a tree and historical building, which marks an important point on a road that linked the North and South, used by refugees and migrants in the 14th century.)

How did you become interested in historical photos?

I studied journalism in college and photography was an important part of this. I’ve also studied the history of photography. So then (from 2000 onwards), I bought many pictures. In the beginning it honestly was just for decoration, but then I bought so many pictures and wanted to know more about them: Who took this picture? And when was this picture taken?

When did this hobby become more serious?

For the sake of this research, I dug up the books I used in college about photography’s history. And after reading these, I discovered a very interesting situation.

Those books of history were all published some time ago, around the 1980s, at the beginning of China’s reform and opening up period. A lot of the primary source materials really haven’t been put out there. There’s very little written about the early history of China’s photography, and there were a lot of mistakes. Why? It’s because they didn’t have access to the first photos. And so, there were a lot of mistakes and there were a lot of things that were missing.

This meant that as I was collecting, I also started doing more research, so I started gathering historical materials.

What did that research look like?

From the beginning of collecting, and discovering mistakes, I wanted to do some research to correct the history. This is to say, I’m not just a collector, I’m also a researcher. In 2004, I wrote my first research article in China Collections magazine (中国收藏杂志 zhōngguó shōucáng zázhì). In 2006, I wrote my first systematically researched article about collecting early Chinese photographs. This was also in a pretty authoritative magazine that was about collecting, and after this many people started to know me.

In 2010, Shanghai held the World Expo. A year earlier, I had held my first exhibition that had gotten some amount of exposure. I had systematically collected all the photos for a collection called “China’s images in World Expos” (世博会中国留影 shìbóhuì zhōngguó liúyǐng). I also published a book of the same name that year.

This was the first collection that became somewhat famous. This was in April of 2009 — one year before the World Expo.

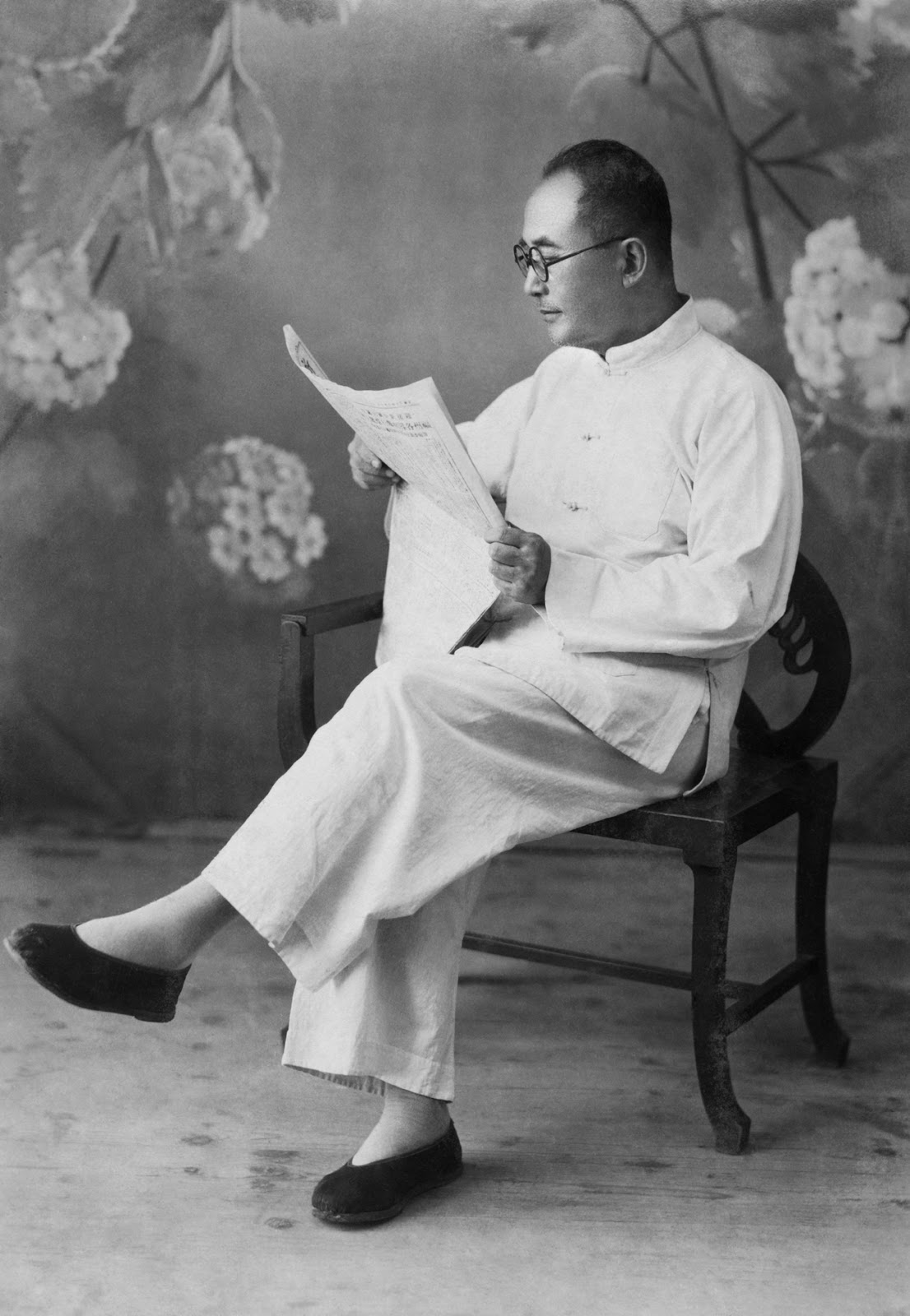

You recently came out with a book about a man (Yè Jǐnglǚ 叶景吕) who has taken a self-portrait every year for 62 years. What’s important about this collection?

I held this exhibit in 2010. This was my second exhibit.

You think, why did he do this? Although when he took a picture every year, that was an individual thing. But when I took his pictures and made them into a collection, I called it Self Gaze (观我 guānwǒ). Looking at him is actually looking at ourselves. When I put this on as an exhibit, I ordered all his photos by year. At the end of these photos, there’s a mirror that’s the same size as the pictures, so that after you’ve seen him, you then see yourself. What does this mean? Why would he go to a photo studio every year and get a photo taken?

This may not be his original meaning, but through my research, I’ve come to this point. By going to the photo studio every year, he has created a pausing point in his life. And through these pauses, he would look back and reflect, to do some kind of summary. It’s also to look ahead, to the next year.

Why do we call it Self Gaze? To look at him, yes, but it’s more to look at ourselves. At the very end, after having seen his life, you will consider your own life. This is to say, collecting is not just for nostalgia’s sake.

Of course, nostalgia is very common. But it’s more about looking at this, to look at our own lives, how do we better our own lives? The lives of our families and friends? A collection has many aspects to it.

Tell us a bit more about your academic work.

My history of early Chinese photography is History of Photo Studios in China. I published this book in 2016, and this was something that took 10 years of gathering materials and writing, and this is my most important work.

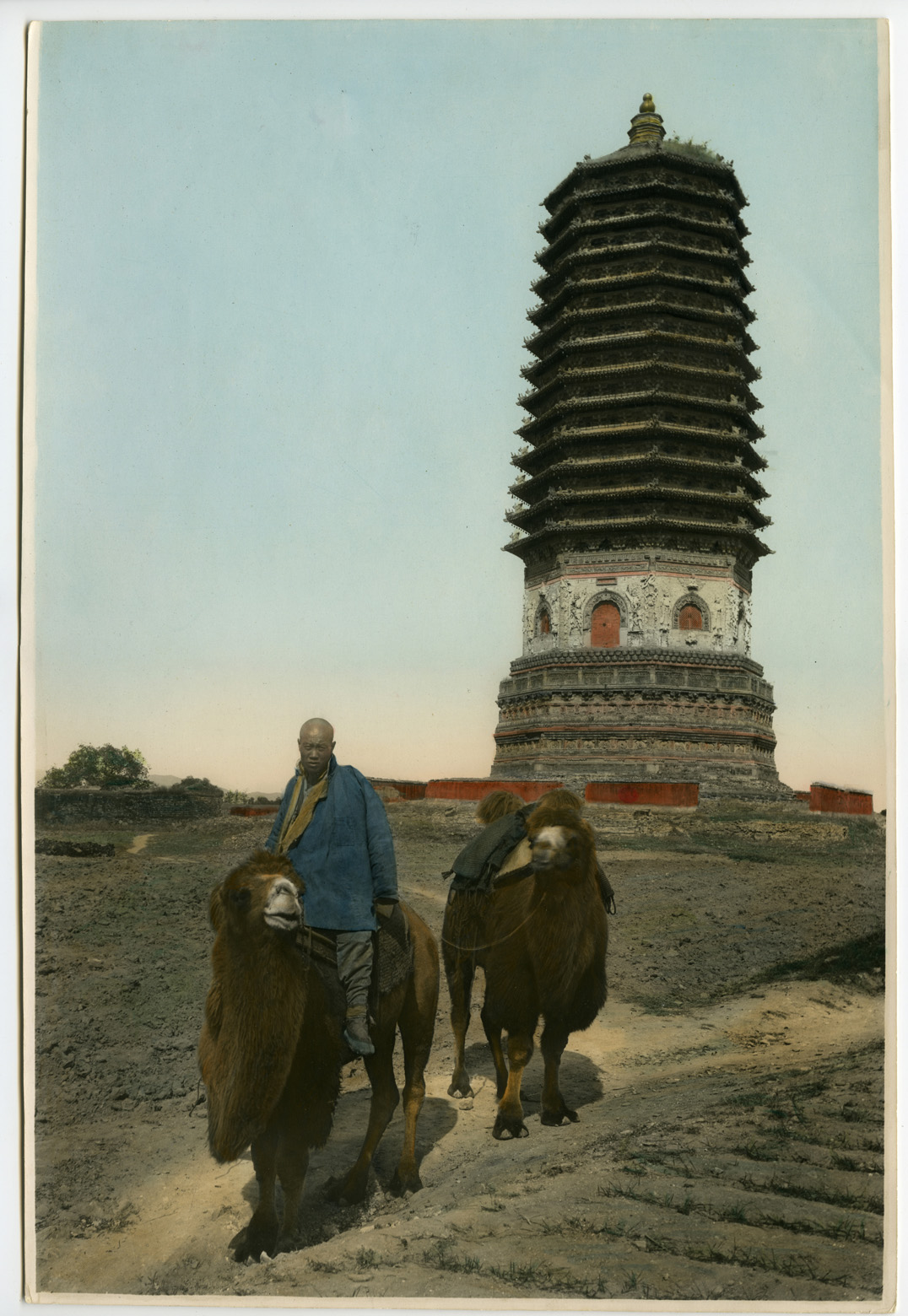

Photography is a foreign good. It came from the West, but after it came to China, how did it develop? The aesthetics that developed here had some distinctive points, I explore this in the book.

For example, Chinese photographs taken by Chinese people — they are all photos of the whole body. Why? In the West, people just took photos of the head, or from the chest upwards. They don’t take full-body shots. This is related to traditional Chinese drawings. The tradition is that in our ancestral portraits and in drawings, Chinese people believe when you have a photo of just someone’s upper half, it’s as if they’ve been beheaded (or cut in half).

What changes have you seen since you started collecting photos?

Twenty years ago, maybe there were two or three collectors. Now there’s definitely several hundred, so the pictures have become more and more expensive.

Why are there more collectors? This also has to do with the development of China’s economy. People have more money now. Twenty years ago, when I bought that first photo, I thought 50 yuan was pretty expensive, because nobody had any spare money. But now, I don’t consider a 5,000 yuan or 10,000 yuan photo as too expensive. It’s only when the economy and society has developed, can these cultural aspects grow. There have been more and more people in this area, and there are also more collectors and exhibits. And Chinese society has started valuing this more.

Originally, when I bought these photos, my parents would ask me, “Why did you buy this? These are all dead people, they’re not even alive.” I didn’t know how to explain it to them, and then when I told them later that this picture could sell for 10,000 yuan ($1,488), then they said, “Oh, then why don’t you keep on doing this.”

You said there wasn’t a lot of interest in buying these old photos or interest in them. Can you say a bit more about that situation?

In the early days, many of the Western photographers’ photos were already in museum collections. My photos — Chinese photographers’ photos of China — no one had collected these. This is an essential difference. Why? One reason is there were more photos by Westerners.

After the establishment of New China in 1949, [China] went through a lot of movements. And the most famous one is 1966’s “destroy the four olds.” Then, we destroyed a lot of old things, maybe these types of things, so if this has survived to this day, then it’s no small feat. And these things, no one had collected them systematically, except in a few places, like Shanghai’s main library.

There have been a lot of exhibitions of foreigners’ photos of China, but Chinese photographs of China are way fewer in number.

Did you want to address this gap — the fact that there was such a great number of Western collections?

Most of the foreigners’ photos, they come from some exoticizing angle, or they’re standing from the point of view of the conqueror. They are really attentive to our beggars, our poor people. They value this more. They have to meet the demand and imagination of Westerners, in their local countries. But for a Chinese photographer, we would focus on beauties and dignities. So, this is two different approaches.

And there are different results.

Did you want to tell the world that China has something to offer in this respect?

Right. I especially emphasize China’s special characteristics. There are a lot of really great professors and researchers across the world who have done research on photography or individual foreign photographers. But for this early Chinese photography, no one had systematically researched this, and after researching, shared their findings in a mainstream format. Maybe it’s because of my background in media. Firstly, I wanted to share this knowledge, and I know how to do this because of my media experience. I had some skills in this area, and through this dissemination want to allow more people to understand Chinese culture.

Mutual understanding is very important. A lot of people may know the photos taken by foreigners of China, but I want to show them the photos that Chinese people have taken, how we view ourselves. There is a different perspective out there.