Forget Seamless: The best Chinese food in NYC is on Yunbanbao

How the Chinese in New York get their lunch delivered.

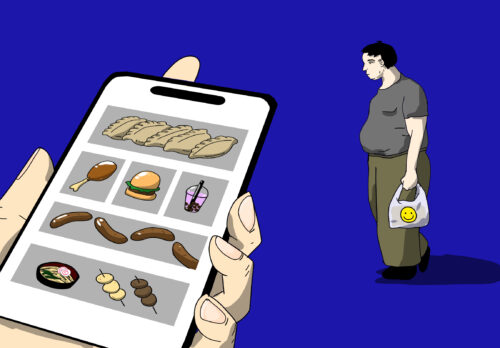

Every day, around lunchtime, outside banks, department stores, and university campuses in Manhattan, you’ll see lines of young Chinese holding their phones, waiting to pick up their meals. They are not waiting for individual deliveries from Seamless, UberEATS, DoorDash, or other delivery services. More likely than not, they’ve all used Yunbanbao (云板报), translated literally as “cloud information board,” a “mini-program” found within the all-everything app WeChat, which every Chinese person has.

Yunbanbao, unlike most food ordering apps, is a bulk-ordering service, functioning as a platform that sends multiple lunch orders to its partner restaurants, most of which are located in Flushing in Queens or Manhattan’s Chinatown. These neighborhoods have the best Chinese food, but are located far enough from major business hubs that it’s unrealistic for most office workers to commute there for lunch. The birth of Yunbanbao satisfies the expat Chinese’s yearning for decent, reasonably-priced Chinese food.

Here’s how it works: Chinese restaurants put out their delivery plans in various WeChat chat groups, each of which maxes out at 500 users (that’s WeChat’s rule, and these Yunbanbao groups fill up fast). The plans are usually in Chinese, and the groups are labeled by delivery location. Users must place their orders at least a day in advance via the Yunbanbao mini-program within WeChat, and then are given a reference number. The next day, when the restaurant minivans arrive in the pickup spots, users get their meals — without a delivery fee — using their reference numbers. They can pay via apps such as Venmo, or cash.

“There always are curious Americans asking where we get our meals when we line up for lunch,” said Alice Yang, a marketing specialist working in the financial district. “When we tell them that we ordered via WeChat, they want to download the app. But they are quickly disappointed as they learn everything happens in chat groups.”

Although it seems tailored to an exclusive group — mostly Chinese immigrants — demand from a loyal customer base keeps the service running. Yunbanbao now partners with more than 100 Chinese restaurants in New York. Each day, it facilitates an average of 1,000 lunch deliveries to nearly 20 locations throughout the city. In the New Jersey suburbs, Chinese immigrants can order dinners through Yunbanbao as well.

The service was founded by Paul Lang and Liu Feng in 2014 in New Jersey, where good Chinese restaurants were scarce. Lang and his business partners started out by facilitating Chinese food deliveries around dinnertime to double-income Chinese families living in New Jersey.

Lang, a former Wall Street data specialist in his 40s, smelled a business opportunity when WeChat became ubiquitous among Chinese friends and neighbors. Chat groups, often formed by location or interest or common connections, offer natural closed-cycle communities for businesses. Many Chinese immigrants organize trips, sales, and classes through WeChat chat groups.

Lang also found that the overseas Chinese, no matter where they are originally from and how their socioeconomic backgrounds differ, share a common fondness for good Chinese food. But the restaurants that serve decent Chinese dishes are concentrated in neighborhoods in New York that have a large Chinese presence, like Flushing and Chinatown. For those living in the suburbs, even if they are willing to pay a hefty delivery fee, restaurants may be reluctant to deliver for a single customer.

“But If 100 people in the same location order food from the same restaurant, the restaurant’s revenue can easily reach $2,000 for each delivery,” Lang said. “We wanted to solve the problem of hungry Chinese not being able to get the food they wanted.”

He set off with his partners to recruit Chinese restaurants in New York to take bulk orders from neighborhood WeChat groups. In its early days, Yunbanbao reached neighborhoods where large numbers of Chinese immigrants live in almost all the East Coast states, as far as North Carolina, Lang said.

Due to difficulties in service quality control, Yunbanbao has scaled back its service area and is now focused on the greater New York area. Most restaurants receive orders via Yunbanbao and do the delivering themselves. In some locations, however, Yunbanbao helps with delivery, too.

In 2018, Yunbanbao started profiting from its service by taking up to 10 percent of the cut from each restaurant. The fact that every step happens in WeChat groups, where restaurants and customers can communicate instantly, saves Yunbanbao from hiring people in customer services, Lang said.

Although Yunbanbao has an English-language app called YBB.plus, designed and tailored for non-Chinese users, the overwhelming majority of its users are Chinese expats in New York and New Jersey, who number over 100,000, Lang said.

Yunbanbao’s popularity has soared in recent years as increasing numbers of young Chinese have gone to study and work in New York. Government data shows the population of Chinese nationals in New York grew nearly 50 percent between 2000 and 2015. By comparison, the city’s overall population increased by about just 7 percent over the same period. This influx of Chinese is particularly visible on the city’s university campuses. The population of Chinese international students at New York University alone more than doubled between 2012 and 2016. Their arrival has brought out a huge demand for diverse, true-to-Chinese-taste Chinese food.

This trend has coincided with the explosive growth of WeChat, the most popular Chinese social media platform, whose users number over 1 billion. In neighborhoods where large numbers of Chinese work and live, there are often not one but several restaurant minivans delivering meals every day.

Yunbanbao, however, has little oversight, so there are problems — like lunches that are already lukewarm upon arrival. Restaurants sometimes cancel delivery plans when not enough people make orders, or because of bad weather. “If the restaurant decides not to deliver, then it doesn’t deliver,” said Eileen Yu, who lives in Jersey City. “There isn’t an accountability system that constrains the restaurants.”

Still, for people like Yang, the marketing specialist, Yunbanbao’s offerings are simply too good and diverse to ignore. One can get anything, from northern China’s signature breakfast, jianbing, to Yunnan rice noodles, Yang’s hometown specialty. Oftentimes she would make lunch plans with Chinese friends working in the same area, pick up their meals, and eat together during break.

Occasionally, when Yang realizes she won’t be able to pick up her ordered food but can’t cancel last-minute, she asks others in the financial district chat group whether anyone would like to buy it off her. Restaurants can often help transfer orders, too.

Yu is also satisfied, overall, with Yunbanbao. It’s the convenience that appeals to her. “You can get all kinds of food delivered via Yunbanbao,” she said, and then started listing them off: “Seafood, Sichuan food, rice noodles, spicy dry pot…”

As for the future of the business, co-founder Lang said the Chinese service is interested in testing waters within the Indian immigrant community next. But he is cautious about his expansion plans, acknowledging that Yunbanbao has a long way to go to break into the American mainstream.

“We are offering authentic Chinese food,” Lang said. “We will enter the mainstream American market only when authentic Chinese food is close enough to [mainstream American] palates that they’ll try it and won’t dislike it.”