Chinese Corner: Why Chinese women don’t use tampons

Chinese Corner: Why Chinese women don’t use tampons

Chinese Corner is Jiayun Feng’s weekly review of interesting nonfiction on the Chinese internet.

卫生棉条诞生90年,为何中国女性很难爱上它?

It’s been 90 years since tampons were invented. Why have Chinese women still not taken to them?

By Yáng Lìyūn 杨立赟

March 8, 2019

A groundbreaking moment on Chinese television I think about a lot is when Olympic swimmer Fù Yuánhuì 傅园慧 casually broke period stigma in 2016. During a poolside interview right after her team finished the 4×100 meter medley relay, Fu apologized to her teammates for her lackluster performance on camera. “I just got my period yesterday, so I am still feeling a bit weak and exhausted,” she said unabashedly, without apparent fear of repercussion. “But this isn’t an excuse for not swimming well.”

The interview turned Fu into an online sensation overnight, sparking an avalanche of positive comments appreciating her courage to break the taboo of women talking about menstruation in public. Amid the chorus of praise, there was one voice impossible to miss. It came from people who genuinely wondered how Fu managed to swim at all.

The confusion is understandable. According to industry research released around that time, only 2 percent of women in China use tampons, whereas in the U.S. that number was 42 percent. The research also found that many in China have never even heard of such a product.

In the past few years, big firms like Procter & Gamble and domestic startups like Femme 非秘 have been working hard to advertise tampons to Chinese women. But the efforts haven’t really paid off. Today, tampons remain a hard sell in the Chinese market.

In this article, author Yang Liyun explores an array of factors that have caused Chinese consumers to be resistant to tampons, varying from the country’s severe lack of adequate sex education to tampons’ relatively high prices compared to pads.

The unsettling case of Yang Yongxin

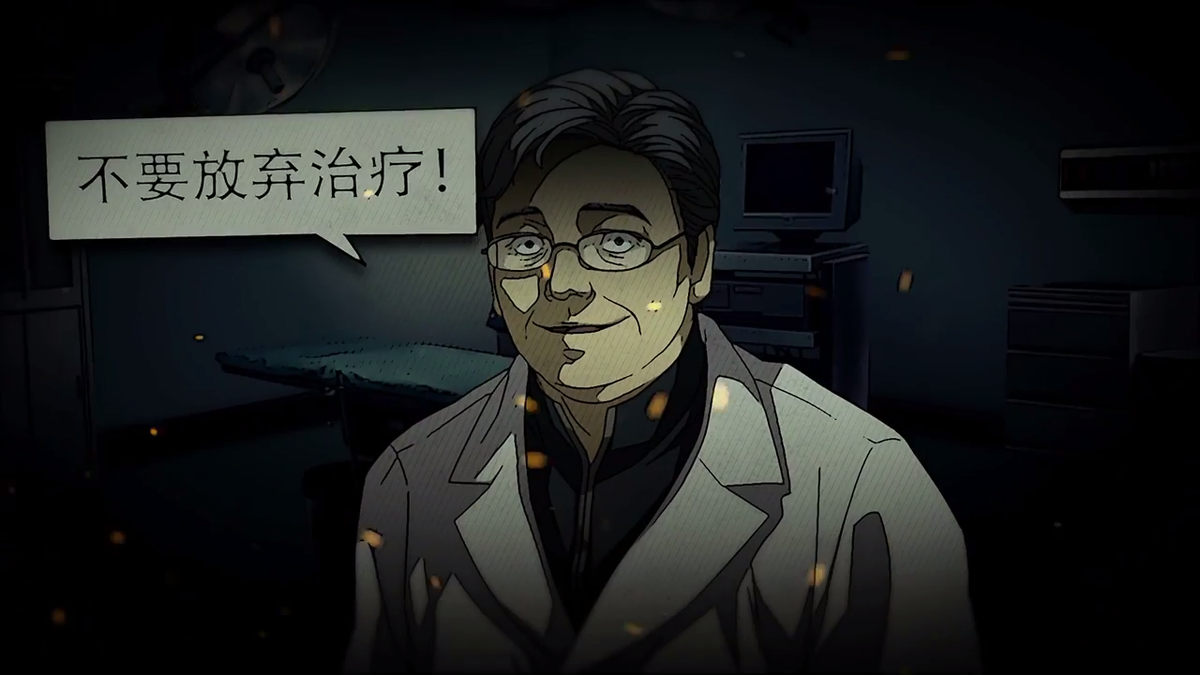

杨永信永不眠

Yang Yongxin never sleeps

By Zhōu Wěihào 周炜皓

March 5, 2019

The Internet Addiction Treatment Center in Linyi, the internet detox camp that made national headlines for using abusive methods such as electroshock therapy on its patients, has finally closed. According to various sources, the facility shuttered last month.

The closure was disturbingly quiet. There was no announcement from the Fourth People’s Hospital of Linyi, which hosted the facility for 10 years. When asked, people working at the hospital all denied the center’s past existence. Local officials were unavailable for comment.

For those who have been following the center’s scandals for years, its abrupt shutdown doesn’t mean the end of the story. Among a host of lingering questions was the accountability of Yáng Yǒngxìn 杨永信, the facility’s former deputy head and an extreme advocate of electroshock therapy, who has found a new position at the hospital as a clinical psychiatrist.

In this goosebumps-inducing profile, author Zhou Weihao takes a deep dive into Yang’s past, revealing how he built a lucrative business by feeding into the irrational fear of the internet among Chinese parents.

Related reading:

- 227个孩子被关进网戒中心,垫起了杨永信的“学术”之路 227 children in the internet detox center were exploited by Yang Yongxin to advance his “academic” career

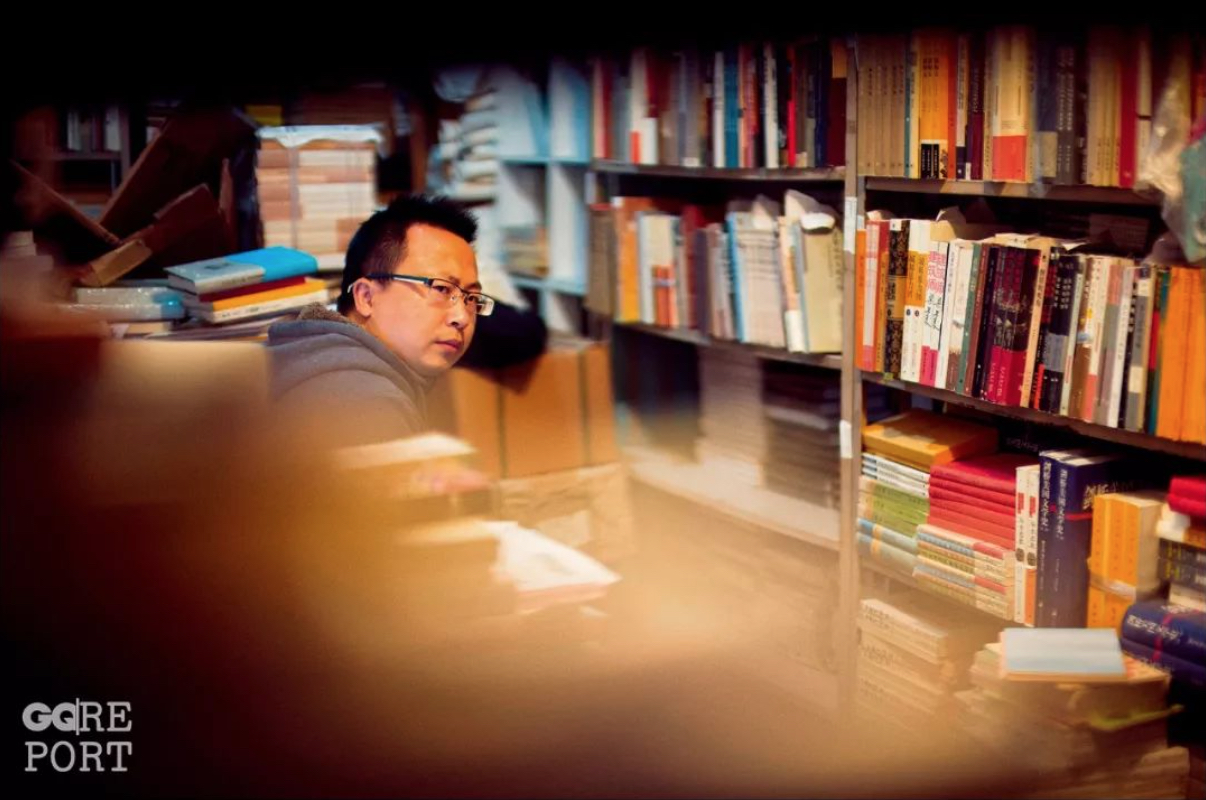

Inside Douban Bookstore, the indie bookshop that never loses its integrity

一家只卖滞销书的书店

The bookstore that only sells unpopular books

By Liú Mǐn 刘敏

March 6, 2019

It’s not news that the independent bookstore business is in rough shape. Last year, Jifeng Bookstore, Shanghai’s iconic independent bookshop chain, shut its doors due to a combination of reasons. Learning from its failure, which was mourned as a huge loss for the bookselling business in China, other independent bookshops have been adjusting their business models to stay afloat.

For example, Owspace 单向空间, which just opened its fourth location in Hangzhou, is now making most of its revenue through events and merch. Meanwhile, SiSYPHE 西西弗书店, which currently owns 180 locations across the country, has fully embraced the mighty power of social media and big data, using AI algorithms to personalize book recommendations and making all of its locations Instagram-worthy. Jīn Wěizhú 金伟竹, the chairman of SiSYPHE who claimed he never visited his own bookstore, once famously said in an interview, “I don’t get why knowing a lot about books as a bookstore owner is plausible. Do you know anything about the market?”

It seems like the Chinese bookstore industry is headed toward a new direction, for better or for worse. But there is at least one bookshop resistant to change, and it is Douban Bookstore in Beijing. Since its establishment in 2005, the bookstore has remained a haven for real book lovers, as well as for its founder Qīng Sōng 卿松, who is willing to protect its authenticity at all costs.

This is a story about how a small indie bookstore survived under pressure from internet retailers and large competitors. It’s also a story about the community of people behind it, who are closely connected through the same passion for good books.

No roles for mature women? China’s problem with middle-aged actresses

谁在抛弃中年女演员?

Who is abandoning middle-aged actresses?

By Ào Nà 奥那

February 17, 2019

It’s a tale almost as old as showbiz: actresses being told that they are too old to play leading roles in TV shows and movies. The lack of older female representation on screen has long been a problem, but the situation is particularly dire in China, where its youth-obsessed entertainment industry vastly prefers young actresses in their 20s over middle-aged ones, who are actually in the primes of their acting careers but are often dismissed as visually unattractive by creatives and executives in casting. To add further insult to injury, the same rules don’t seem to apply to their male counterparts. As a result, women in China’s showbiz world have to face the double discrimination of ageism and sexism, which has led to some truly mind-boggling casting choices, such as actress Liú Mǐntāo 刘敏涛, at 39, playing mom to Wáng Kǎi 王凯, an actor five years younger than her, in the 2015 historical drama Nirvana in Fire 琅琊榜.

A legion of Chinese actresses, having reached their breaking point with the rampant age discrimination, have publicly expressed their frustration. In the 2017 reality show I Am a Actor 我就是演员, several actresses over 30 complained about the issue, saying that roles dried up significantly for them when they reached a certain age. Sòng Dāndān 宋丹丹, a prominent sitcom actress and comedian, once revealed that in the nearly 10 years after she hit 35, her career was at a depressingly low point where she was constantly turned down by directors.

Echoing their complaints is a growing audience that has been calling for more middle-aged women to play leading roles in entertainment. The demand for changes, mostly from female viewers, is so widespread that it has resulted in some substantial progress. An encouraging example of this is The Lady 淑女的品格, a TV show that’s in the making that features four professional women over the age of 40. The idea was inspired by a viral post on Weibo last year in which an internet user photoshopped four of her favorite middle-aged actresses together in a self-made poster. “I’m begging investors, screenwriters, directors, and producers to cast more women over 40,” the person wrote. “The poster is fake, but my wish is real.”

While it’s far too soon to say that a bigger paradigm shift is taking place, the future looks optimistic for middle-aged actresses in China. As author Ao Na argued in this article, the hunger for the stories of mature and independent women exists and is rapidly growing. The Chinese TV and movie industry will eventually come to the realization. It’s just a matter of time.

Related reading:

- 我们的女性剧集,该检讨什么? What goes wrong with our female-led TV shows?

Below are some of the best things that I enjoyed reading this week:

- 红极一时的「鉴宝」节目都去哪儿了? What happened to China’s once-popular antiques appraisal shows?

- 在中国,最便宜的装逼方法叫星巴克 In China, drinking Starbucks is the easiest way to fake an ostentatious lifestyle

- 谁杀死了“味精大王”? Who killed “the king of MSG”?

- 煎饼摊有多赚钱?How much money can you make by making jianbing?

- 洛阳亲友如相问,我在北京租房子 When relatives and friends from my hometown ask how I’m doing, tell them I’m looking for a rental in Beijing

“The difficulty of finding an affordable rental is probably the best criteria to assess how much of an outsider you are in a foreign place. This is especially true in Beijing.” - 男色经济学 The economy of good-looking men

“For investors in the Chinese entertainment business, there is no need to care about what straight Chinese men are thinking. What they don’t understand is where you can make the most money.”