The brief and scandalous film career of Madame Mao

Before she became the most powerful woman in China and imposed her vision of art and culture on the country, inflicting untold violence along the way, Jiang Qing was known as Lan Ping — “Blue Apple” — and was a middling actress whose failures would shape the person she would become.

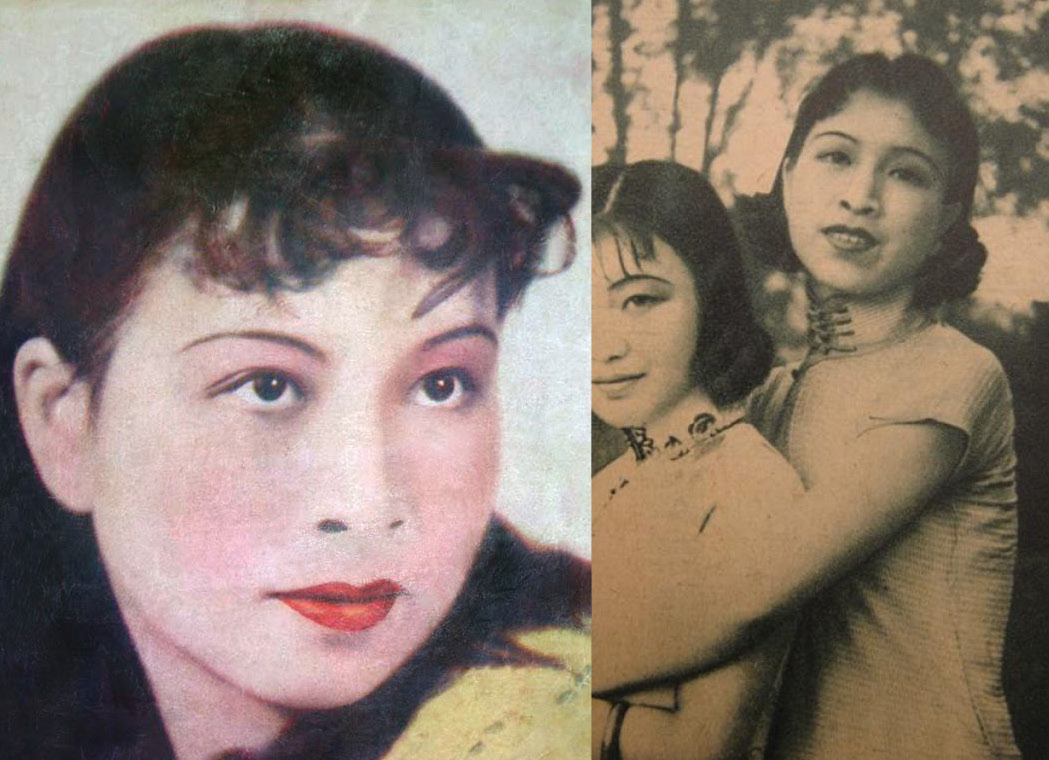

It’s well known that Jiang Qing 江青, or “Madame Mao,” was an actress before marrying Communist China’s Great Helmsman. She got her start acting in theater troupes, and for a period of four years, lived in Shanghai and worked in the city’s glamourous film scene. In later years, Jiang became embarrassed of her past, but she remained committed to Chinese art and culture. During the Cultural Revolution, Jiang helped oversee the creation and promotion of the period’s Eight Model Operas, a group of revolutionary-themed pieces that were the only pieces of work allowed on Chinese stages at the time. While engineering movie adaptations of these operas, Jiang was simultaneously purging and wrecking the lives of many of her old associates and friends from her Shanghai days.

There was a lot for Madame Mao to hide. The movie industry in 1930s Shanghai was considered bourgeois and decadent, populated by egotistical and wild people. Jiang’s brief career seems to have fit into this stereotype well. According to Australian historian Ross Terrill’s biography Madame Mao: The White-Boned Demon, there were all sorts of hijinks during this time of her life. On one occasion, Jiang went out to a Russian restaurant and got extremely drunk with fellow actress Wang Ying 王莹 and her husband. When Jiang got up the next morning, she found herself naked in her room, with a warning in red lipstick on her stomach: “BE CAREFUL NEXT TIME, GREEDY DRINKER.” In her bout of drunkenness, actor and director Yuan Muzhi 袁牧之 had taken Jiang to her room and stripped her as a prank.

Jiang’s acting won her some fans, but she was never as popular as co-stars like Li Lili 黎莉莉. Had Jiang never become a political figure, chances are that her scandalous personal life would probably have been better remembered than her lackluster movie career. Even back then, she was difficult to please, as quarrelsome as she was ambitious. When Jiang came to Shanghai in 1933, she had just left a life behind in Qingdao. Going by the name Li Yunhe 李云鹤, the 19-year-old woman had studied at Qingdao University, fallen in love with Communist activist Yu Qiwei 俞启威, and had been active in the local theater scene.

After arriving in Shanghai, Li played in amateur theater troupes and supplemented her income by teaching night classes. Her former husband Yu had been arrested in Qingdao due to his political activities, and Li suffered the same misfortune in Shanghai. She was kept in prison for three months, and after she was released, decided to change her name to Lan Ping 蓝苹, or “Blue Apple.” Lan would keep this new name for the remainder of her career in Shanghai. Having reinvented herself, it wasn’t long before Lan got her breakout leading role, playing the rebellious housewife Nora in Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll House. Shanghai theatergoers were swept away, and Lan’s role was so acclaimed that the Diantong Film Company quickly offered her a contract.

Tang Na 唐纳, a movie critic, actor, and director affiliated with Diantong, was one of Lan’s admirers. He was smitten with Lan’s acting and good looks, and Lan was a fan of his own work. The two colleagues got to be friends, and soon enough, began dating and living together. They shared political views, and had similarly troubled childhoods, but Lan and Tang also had strikingly different personalities. Lan was tough and independent, while Tang was known for being gentle and more docile. At first, they seemed to be sincerely in love. They indulged in the city’s night life, eating at Russian restaurants, dancing with their friends, and frequenting the theaters.

Their clashing personalities and goals, however, turned their relationship toxic. The couple frequently butted heads and bickered, and when Lan discovered love letters from Tang’s old girlfriend Ai Xia 艾霞, she thought it was time to break up. Tang threatened to commit suicide, a plan that convinced Lan to stay and forgive him. At the age of 22, Lan agreed to marry Tang, apparently out of economic necessity. The marriage did nothing to rekindle their affection, and neither spouse was much faithful to the other. Their relationship swung between constant arguments on some days and repeated declarations of love on others. Career-wise, Lan’s outlook wasn’t any brighter, playing only small parts in her Diantong performances.

When Diantong went out of business, Lan became desperate to find work. Zhang Min 章珉, the director who casted her in A Doll’s House, luckily gave her the lead role in his production of Alexander Ostrovsky’s The Storm. Rumors spread that Lan was sleeping with Zhang, and the suspicion was strong enough for the director’s wife to move out of their house. The controversy added more fuel to the fire between Lan and Tang, leading Lan to retreat to Jinan to recover and visit family. Tang, the more invested of the couple, followed after her. As if they were playing in a melodrama, Lan claimed to be so hurt that she refused to see him. On cue, Tang attempted suicide again, overdosing on sleeping pills at an inn. He miraculously survived the attempt, and after Lan was notified by the inn to fetch her despondent husband, the couple returned to Shanghai.

Lan was far too free-spirited to settle down. She was only afraid, if she left, that Tang might lose his mind and kill himself for real. When Lan finally confessed that she no longer loved Tang, the two agreed to separate secretly, in order to keep their split out of the press. Things only escalated from here. Tang showed up at Lan’s apartment, and Lan ended up hitting him, since she warned him on a previous occasion not to come around anymore. Tang returned the favor, and after leaving, tried drowning himself in the Huangpu River. He survived, but Lan didn’t come back this time. She was done, and by May 1937, Lan and Tang were properly divorced.

1937 should have been a good year for Lan. She was fresh off a supporting role in Blood on Wolf Mountain 狼山喋血记, an anti-Japanese allegory released in November 1936. In a village being harrassed by wolves, Lan played a wife who casts aside her fears and fights back. She co-starred with celebrity actress Li Lili, and a few months later, got the part as leading woman in Wang Laowu 王老五. In this tragic drama, Lan played a poor girl who feels obligated to marry a wanderer named Wang after he helps her sick, dying father. Both of these performances seemed like they would boost Lan’s career, but there were a couple of problems blocking her path.

One was the public reaction to her breakup with Tang. The press had a field day with the scandal, and gossipy articles and Tang’s friends attacked her for the divorce. The outrage was so bad that Lan penned an article defending her decision. Another factor was political. Communists were still being arrested, and the fighting with Japan greatly damaged Shanghai’s film industry. In July of 1937, Lan was ready to call it quits and reinvent herself again. She took up the name Jiang Qing, headed to the Communist stronghold of Yan’an, and married Mao Zedong in November 1938.

Jiang Qing’s former life as an actress was nothing exceptional. She was jealous and petty, and blamed her failure on people who she claimed had cheated her. When the Cultural Revolution rolled around, Jiang was determined to erase the past, yet also take revenge. She wanted every memory, picture, and piece of writing about her acting to be destroyed. Red Guards raided the houses of five of Jiang’s old contacts, on the search for anything related to her. Jiang’s old friend Wang Ying was persecuted and imprisoned before dying in jail in 1974. One-time co-star Li Lili and her entire family was hounded on the orders of Jiang. Both Li and her filmmaker husband were tortured, and her husband preferred to kill himself rather than endure the abuse. Jiang was ruthless, and many more people were sadly humiliated, tortured, and persecuted until the point of death, solely because they once knew a third-rate actress who called herself Lan Ping.

Film Friday is The China Project’s film recommendation column. Have a recommendation? Get in touch: editors@thechinaproject.com