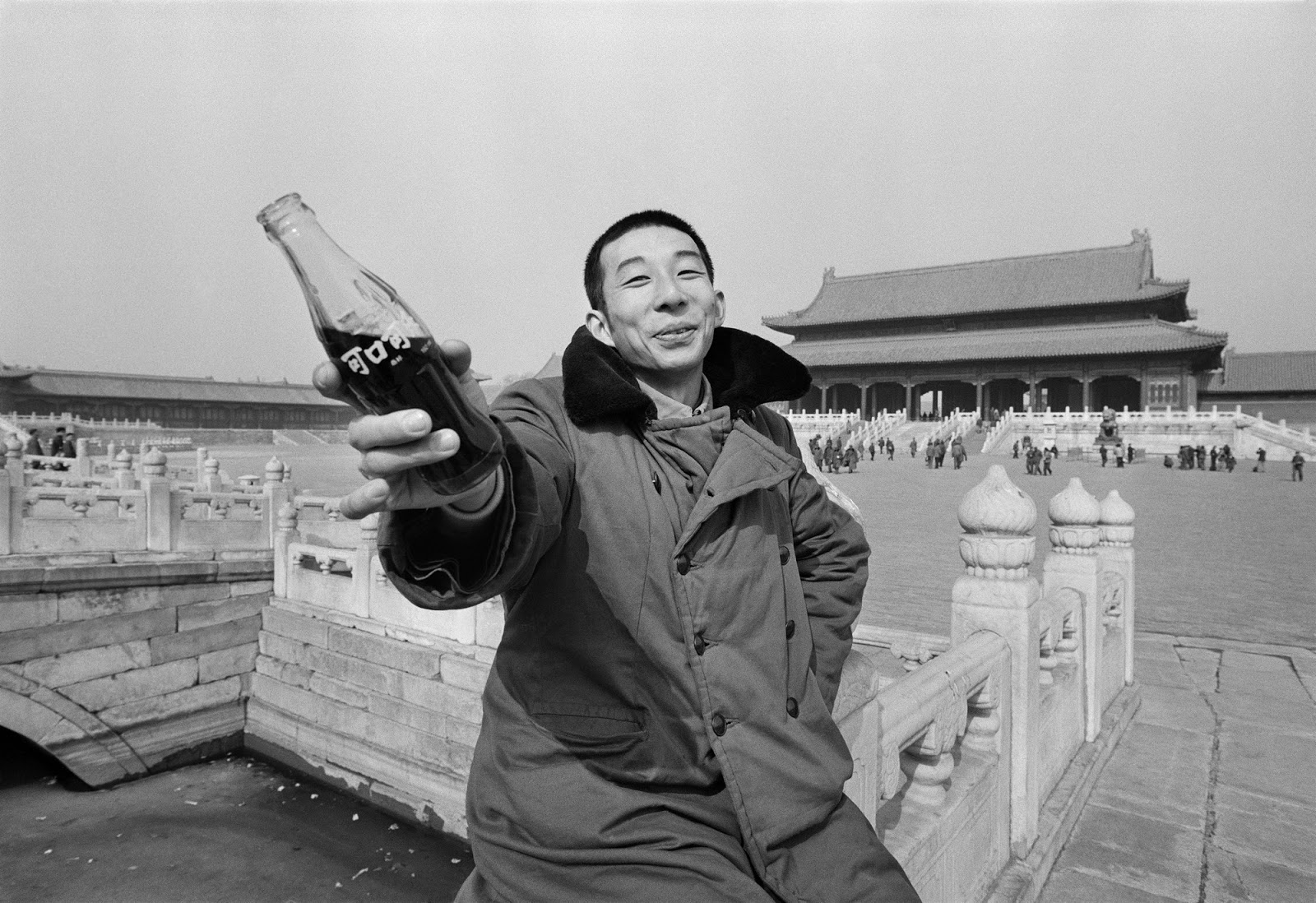

‘A Life in a Sea of Red’: Q&A with Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer Liu Heung Shing

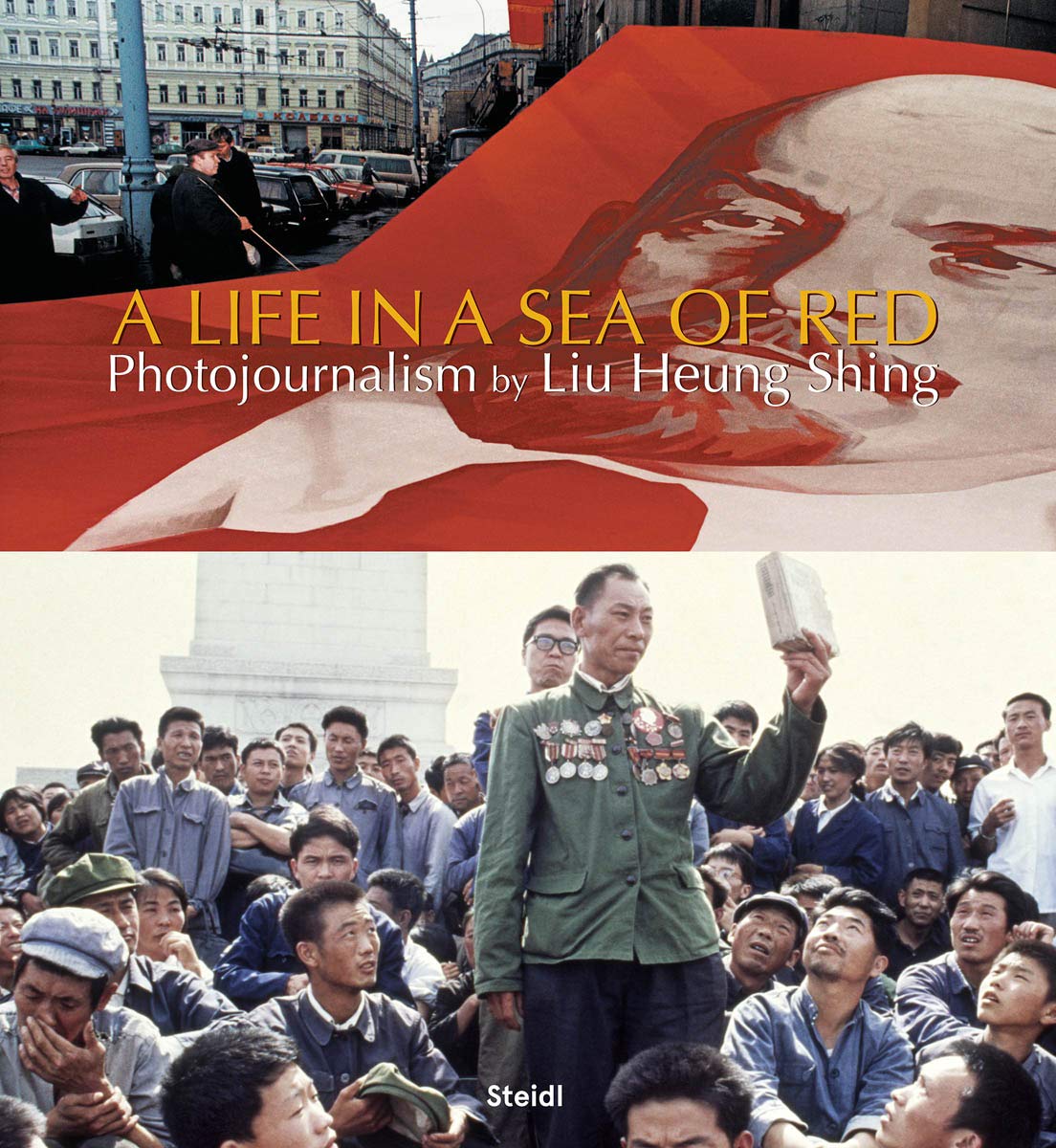

Pictured: “Coca-Cola: Feel the taste!” A young man proffers the iconic glass bottle which symbolizes Coca-Cola around the world. The Coca-Cola company had just resumed production in China. Forbidden City, Beijing, 1981

“Watching China is a work in progress.”

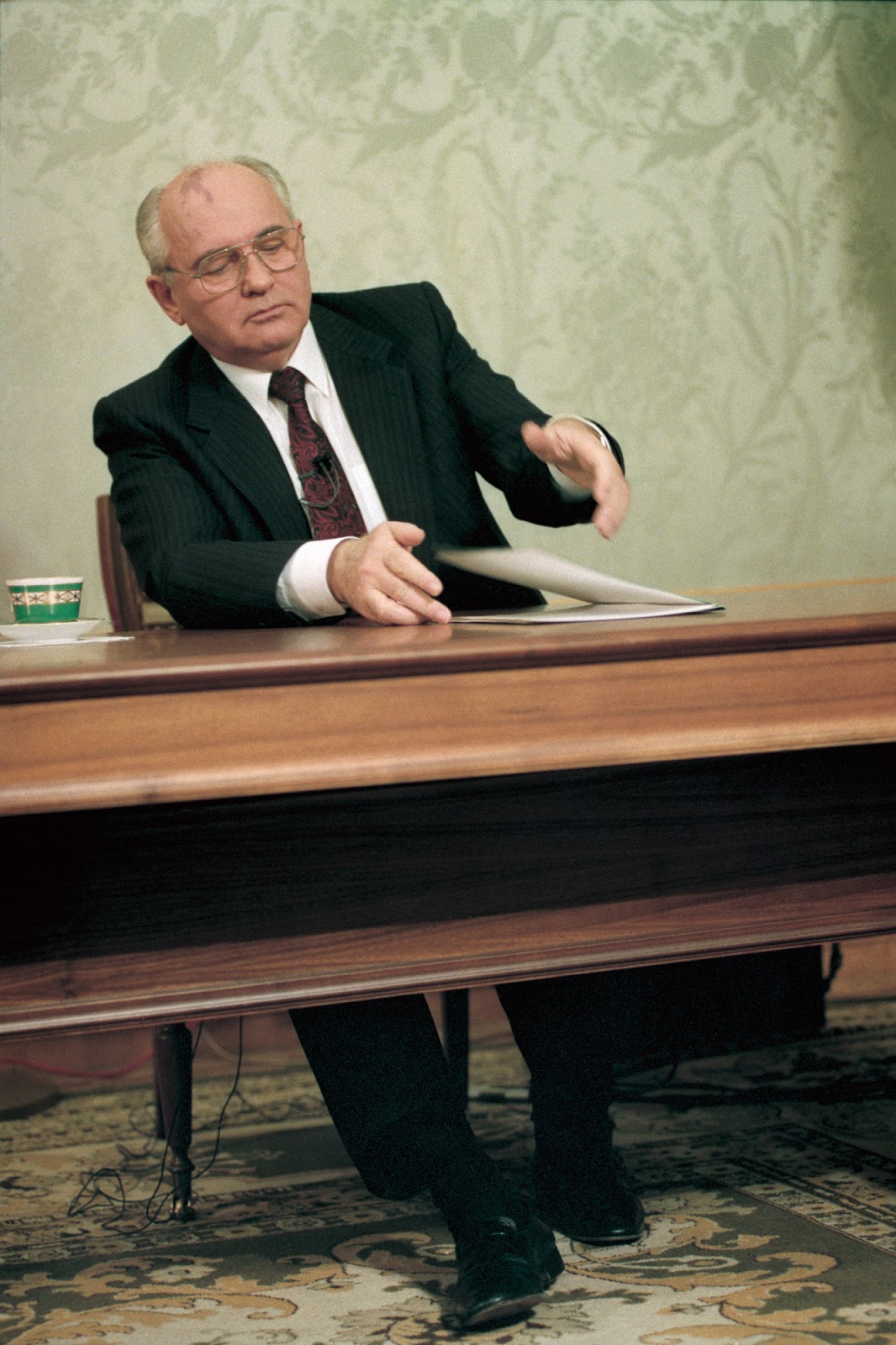

Liu Heung Shing 刘香成 is one of the few photographers out there who wears reading glasses. They’ve accompanied the 68-year-old throughout his entire award-winning photojournalism career, from China to India to South Korea to Southeast Asia to the Soviet Union. The only times he didn’t have them on were during violent protests, when he would have to wear special tear gas masks — with a prescription frame, of course, so that he could still focus his camera.

Born in Hong Kong in 1951, Liu went to primary school in his hometown of Fuzhou in southeastern China. As a child of a landlord family, he underwent bullying for his political status, and later witnessed famine during the Great Leap Forward.

After studying at New York’s Hunter College and apprenticing with Life Magazine, Liu began photographing China in 1976; his first assignment was covering Mao Zedong’s death. Later, he worked for the Associated Press until 1994, capturing China’s reform and opening up, the 1989 Tiananmen protests, and the Soviet Union’s collapse. He shared the Pulitzer Prize for Live News Photography Award in 1992 for covering Mikhail Gorbachev’s announcement of the Soviet Union’s dissolution.

Much of his best work has been collected in a forthcoming book, A Life in a Sea of Red, which spans most of his time covering China and Russia from 1976 to 2016. It’s no accident that the book’s release falls during a special year for China — the 100th anniversary of the May Fourth Movement, 70th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China, 40th anniversary of China’s reform and opening up, and 30th anniversary of the Tiananmen protests. “If this isn’t a significant year, then I don’t know what year is,” Liu said.

“Observing the Mainland from near and from far — as a student — I knew that China was going to be the biggest story of the era,” Liu wrote in the book’s epilogue. “I wanted to understand it, to be able to tell stories about life in China without being constrained by restrictions that were ideological, be that the dogmatic Communist ideology, or the prevailing narrative of the West.”

The book’s title is an adaptation of the Chinese phrase “Alive in the bitter sea” (苦海余生 kǔ hǎi yú shēng), which means surviving amid hard circumstances. In Liu’s view, that aptly describes what Chinese people experienced during the first decades of the People’s Republic of China.

Before the book’s U.S. release in June, I spoke with H.S., a nickname he prefers, in Hong Kong. The interview has been slightly edited for conciseness.

Ying Wang, The China Project: Many of your photographs on China and Russia have been published in books you authored or edited, which span from 1949 to 2008. What motivated you to work on this new book?

H.S.: The result of the changes that took place in China and the former USSR continues to evolve into the 21st century. I felt it was important, from a photojournalistic point of view, to keep a record of my reporting, particularly of the daily lives [of people] in these two countries, as one rose and one collapsed.

The China Project: You left news reporting in 1994, then founded a magazine in Hong Kong, and then spent almost 10 years as an executive for Time-Warner and News Corporation in the mainland. Now, you’re the founder of Shanghai Center of Photography. How has your post-photojournalism career changed your perspectives on China?

H.S.: It hasn’t. Watching China is a work in progress. I find myself in an unenviable position. I tell the Chinese that the world is not like this, it’s not like as you imagine. And I tell my American colleagues and American readers that China is not like that. So in today’s world, information — even [found in] photographs — is very fragmented. I think people tend to see the world in black and white. But the world [is filled with context, which] you can see in photography. You can see that in the photos in my book. So what has caused the rapid change? You have to understand China’s first 35 years to understand why it was in such a rush in the second 35 years.

The China Project: But do you think you now have a better understanding of China after these years?

H.S.: No, I don’t. I cannot make that claim. Every day I look at China, I feel I understand it less. Because I find the more I understand it, the more complex it is.

The China Project: As the book contains photographs from the 1989 Tiananmen protests, which remains a taboo subject on the mainland, were you concerned with any impact that might have on your life in Shanghai, or book sales?

H.S.: China will not publish [the book], and it cannot be imported into China. Censorship in China has been around for 70 years, and it’s not about to change because of my book or anybody else’s book. We have to deal with the world as it is. So what else is new? I’ve also had books published in China. They took out [some] photographs, and then [the books] got published. In my mind, they’re widely being circulated and read by people born after the 1990s, so I feel like I’m still contributing to the conversation.

The China Project: You held an exhibit titled China Dream: 30 Years in Shanghai in 2013. But you told a Hong Kong newspaper that the images conveyed a story far different from that of the Chinese government’s. Since your new book includes more recent images, do you think it illustrates the “Chinese dream”? Is it still different from the official narrative?

H.S.: Yes, Chinese people, like [people everywhere], pursued material gains in those days. They needed coupons to buy food, to buy cooking oil. Today, these are not their concerns anymore. So they drive around in Mercedes-Benzes. They travel. They are in the art market. All these things are in the photographs. The Chinese dream, as articulated by the government, is the want for the whole world to understand China. In that sense, I don’t think they are there yet.

The China Project: What’s next for you?

H.S.: I don’t have any immediate plans. But I have a lot of exhibition plans for the Shanghai Center of Photography. [Check it out here.]