Kuora: What is the most admired Chinese dynasty?

This week’s column comes from one of Kaiser’s answers originally posted to Quora on January 19, 2015.

What period of Chinese history do Chinese most admire?

Many Chinese are very admiring of the Tang (AD 618–907), especially the years before the An Lushan Rebellion that broke out in 755.

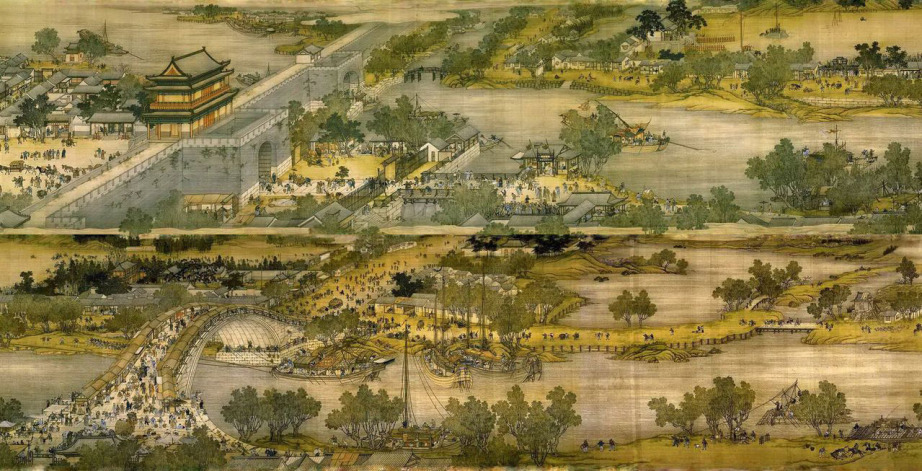

The Kaiyuan Shengshi (开元盛世), the first part of the reign of emperor Tang Minghuang (Xuanzong), who ruled from 712 to 756, was considered to be the apogee of Tang splendor. During this time the Tang capital at Chang’an was the largest city in the world, with a roughly square city wall with a perimeter of 35 kilometers and a population of over a million. It was an extremely cosmopolitan city, sitting as it did at the eastern terminus of the Silk Road, and people from all over the known world of the day could be found there. There were Nestorian Christians, Manicheans, some Arab Muslims, Indian Buddhists, and even some Jews living in Chang’an. You could encounter Central Asians from as far west as Persia to the easternmost reaches of the steppe corridor, Japanese, Koreans, Malays, and more in the great markets.

There was a craze for the exotic that’s very clearly reflected in the art and music of the time. Ceramics and statuary often depicted foreign peoples — Sogdians, Persians, Turks — and the exotic animals they introduced, like Bactrian camels. It was during this time that Buddhism really took hold in China. Central Asian music — and the instruments on which it was played — took over as the dominant form of music, the pentatonic music that we recognize as “Chinese” today. Instruments used in Chinese music still bear names that reveal their foreign origin: the pipa (a borrowed word), the erhu (“second barbarian [fiddle]”), the huqin (“barbarian lute”), and so forth.

The three-colored Tang sancai glaze became very popular during this time and these pieces remain very valuable to collectors today. The poetry of the Tang is memorized even today by most Chinese schoolchildren in the PRC, greater China, and in the diaspora. Most Chinese can recite at least a couple of famous Tang poems by the likes of Li Bai, Du Fu, Wang Wei, and Li Shangyin.

The Tang aristocracy was still heavily influenced by the nomadic Turkic peoples with whom its ancestors had heavily intermarried in the preceding centuries. They still regarded horsemanship and archery as vital arts for men, and early Tang emperors even pitched felt tents of the sort used by steppe nomads in the imperial palace grounds. With its powerful military forces, matching their traditional enemies out on the steppe in the use of horse archery, the Tang were able to extend their power west into Turkestan all the way out to Afghanistan.

In 751, scouting parties from the Arabs of the Abbasid Caliphate and the Tang Chinese fought a minor but historically significant skirmish at the Talas River in modern Kyrgyzstan, marking the easternmost point of Arab expansion and the westernmost point of Tang.

Tang’s military might, however, was dependent on powerful regional generals who commanded personal loyalty from their mostly nomadic or semi-nomadic cavalry forces. This proved to be a serious problem. Tang Minghuang grew infatuated with an imperial consort surnamed Yang, known to history as Yang Guifei (“Precious Consort Yang”), who ended up accruing considerable power and influence at court. She helped install her second cousin, Yang Guozhong, as Prime Minister. Her “adopted son” and reputedly also her lover, the Sogdian general An Lushan, also became highly influential at court, and clashed with Yang Guozhong. He rebelled in 755 and effectively brought an end to Tang’s splendor. The rebellion was eventually put down in 763, but not before Chang’an had already been sacked by Tangut (Tibetan) forces and the whole country wracked with civil strife. The dynasty survived but never quite recaptured its earlier magnificence. A kind of xenophobia set in in the early 9th century, and foreign influences — especially in the military and in religious life — became very unpopular.

Kuora is a weekly column.