‘Iron Moon’: A beautiful portrait of China’s working-class poets

Is there room for poetry in contemporary society? Iron Moon, an award-winning documentary that splices together the working-class life of its subjects with their work, suggests poetry is more important now than ever.

The Taiwanese company Foxconn is known for manufacturing a handful of popular electronics, including video game consoles and Apple products. Although it’s headquartered in Taiwan, Foxconn has factories around the world, including in mainland China. In 2010, the company made international news when reports surfaced of a spree of worker suicides in response to low pay and harsh working conditions. To prevent more employees from leaping off their buildings, Foxconn notoriously set up safety nets at some locations.

These nets have allegedly worked, to an extent, but suicides have continued on a smaller scale throughout the decade. One of those was a 24-year-old named Xu Lizhi 许立志, whose poetry, published posthumously, has raised national awareness of the plight of workers like him. After his suicide in September 2014, Xu’s poems capturing life as a factory worker were read and shared across the internet. His poem “I Swallowed an Iron Moon” (我咽下一枚铁做的月亮 wǒ yàn xià yī méi tiě zuò de yuèliàng) expresses Xu’s frustration with the industrial environment around him, comparing a screw to an “iron moon.”

Xu’s poem also lends its name to Iron Moon, an alternate English title for the Chinese documentary The Verse of Us 我的诗篇. The film includes a section on Xu’s life and work, and follows five other contemporary poets from China’s working class. It’s a brave subject, and certainly a commercially risky one. Directors Wu Feiyue 吴飞跃 and Qin Xiaoyu 秦晓宇 had trouble with funding, but a crowdfunding campaign saved its production with the backing of more than 1,300 donors. When the film premiered in 2015, it won awards from several Chinese competitions, along with nominations for the categories of Best Documentary and Best Film Editing at Taiwan’s Golden Horse Awards.

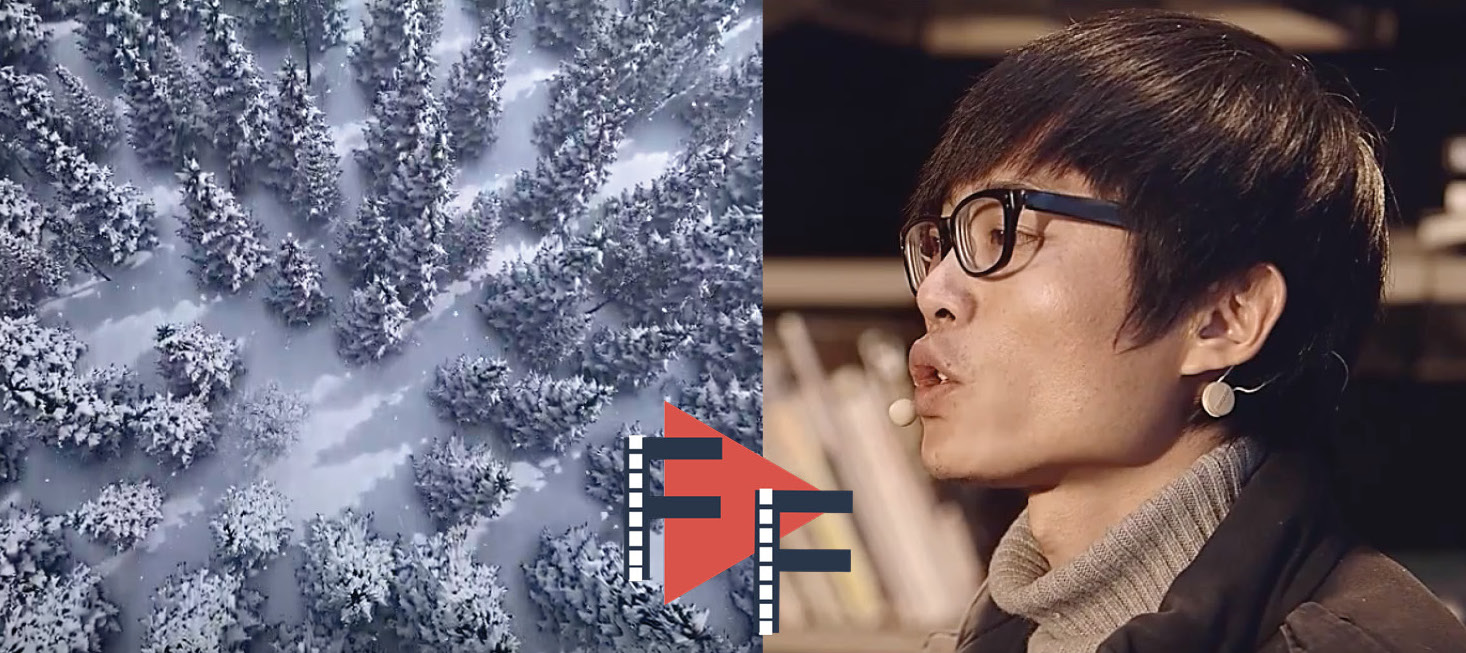

Iron Moon is a powerful film, and portrays a class of people seldom seen on the screen. The first worker-poet the viewer is acquainted with is a man named Wu Niaoniao 乌鸟鸟. At a public reading, Niaoniao performs his poem “Rhapsody on the Advance of Heavy Snow” (大雪压境狂想曲 dàxuě yājìng kuángxiǎngqǔ), intercut with scenes of snow falling onto trees, people, and an urban road filled with cars. Niaoniao is an unemployed forklift driver, and struggles to find new work. Later on in the film, Niaoniao goes to a job fair, baffling the recruiters. At one point, he tells somebody that he can write poetry, only for the man to ask back, “What do you do?”

Jike Ayou 吉克阿优 is the second poet; he’s introduced writing a poem while he rides a train with his little boy. Ayou is a member of the Yi people, one of China’s ethnic minority groups. He is shown visiting his family in a rural village in Sichuan. The third poet, Wu Xia 邬霞, is a garment worker living in Shenzhen. She tells the camera that she’s an introverted person, and wishes that she could live as free as a bird. She loves dresses, but can only dream about being able to afford the stuff she’s hired to make. One of her poems describes ironing a dress, and is addressed to whatever unknown girl ends up buying it.

The fourth poet, Chen Nianxi 陈年喜, is a demolitions worker who digs and blows up rocks in mines. It’s a miserable and dangerous job, but Nianxi’s sick parents and wife and son are all dependant on him. Alone in his room after a hard day’s work, Nianxi writes a poem to the son he has to live away from. The final poet is Lao Jing 老井, a coal miner with 25 years of experience under his belt. Jing is the oldest poet featured in the film, and the poem he shows is a commemorative piece about some fellow miners who had died in a work accident.

Throughout the film, Iron Moon alternates footage from the daily lives of its poets with readings of their work set to imagery, music, and on-screen text. I found the music too sentimental for my tastes, but the poems themselves pack quite a punch, as often hopeful as they are sad. Near the end of the film, there is also a section about Xu Lizhi, including a heartbreaking interview with his parents. In a country (and world) increasingly occupied with money and technology, Xu’s father is skeptical that poetry can have any power or influence today. He thinks, had his son Lizhi never died, he might never have become famous.

Is there still room today for poetry? Xu’s father and Niaoniao’s job recruiters might say no, but the message of Iron Moon suggests otherwise. No matter what obstacles its poet-workers face, they hang on and persevere, using poetry as a vehicle to console and express themselves. While it’s a valid argument that only political and social reforms can change the situation of China’s suffering working class, Iron Moon shows poetry gives these dispossessed people an outlet which allows them to be heard.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iuKNHO-XwmE

Film Friday is The China Project’s film recommendation column. Also, we’re celebrating National Poetry Month by looking at Chinese poetry, past and present. Follow our series here.