Release delay of war epic ‘The Eight Hundred’ — a new era of Chinese movie censorship?

It has been an exceptionally chaotic month for Chinese movies. After the last-minute withdrawal from its international debut at the Berlin International Film Festival, teen drama Better Days (少年的你 shàonián de nǐ) announced last week that it had postponed its original June 27 release date indefinitely. A string of other films, such as the coming-of-age movie The Last Wish (伟大的愿望 wěidà de yuànwàng), were ordered to come up with new titles before hitting theaters. To fill the void caused by these abrupt delays, some movies, such as Looking Up (银河补习班 yínhé bǔxíbān) and The White Storm 2 — Drug Lords (扫毒2: 天地对决 sǎodú 2: tiāndì duì jué), decided to come out sooner than planned. And as all this was going on, The Eight Hundred (八佰 bābǎi), a much-anticipated high-budget war epic that was due to appear on the big screen on July 5, also had its release date pushed back.

In a terse statement (in Chinese) published on Weibo on June 25, Huayi Brothers Media, the leading Chinese studio that spent a massive budget of $80 million on the movie, did not give a specific reason for the delay other than vaguely saying it is a decision made by the production team and other parties involved. “The movie will temporarily withdraw from the summer lineup window,” the entertainment enterprise wrote, adding that a new release date will be announced at a later time.

It’s not uncommon for Chinese movies to be hit with unexpected delays, which are usually assumed to be because of censorship trouble associated with the State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film, and Television (SAPPRFT). But the case of The Eight Hundred is rather unusual, given that the film was reportedly granted permission from SAPPRFT before starting production and that the producers had already spent heavily on promotion before the sudden cancellation.

To shed more light on this confusing matter, @院线经理人 (Movie Theater Manager, yuànxiàn jīnglǐrén), a WeChat blogger with a focus on the movie business in China, wrote an article (in Chinese) that gives an in-depth explanation of the whole affair. According to the author, while The Eight Hundred faced no opposition by movie authorities, it failed to receive an official screening permit due to obstacles created by some forces outside the movie industry.

There has been widespread speculation amongst movie critics and industry insiders that The Eight Hundred’s problems were caused by an organization called the Red Culture Research Association of China (中国红色文化研究会 zhōngguó hóngsè wénhuà yánjiū huì). Founded in 2010, the association is dedicated to spreading the Communist Party’s cultural ideologies by organizing speech contests, lectures about the Party’s history, and conferences focused on the promotion of Xi’s “Chinese Dream.”

Earlier this year, the organization held an academic seminar to discuss problems regarding “the creation tendency of Chinese movies,” in which The Eight Hundred was a main target of criticism for “overly glorifying” the heroic role of Chinese nationalists (Kuomintang) and downplaying the Communist Party forces in the Second Sino-Japanese War. While the movie’s production team insisted that the story is true to history, the timing of its release caught the attention of the Red Culture Research Association: This year marks the 70th anniversary of the founding of the Republic of China. As @院线经理人 points out, in a hyper-sensitive time like this, a movie that makes the Kuomintang good was naturally subject to criticism attacking its political insensitivity.

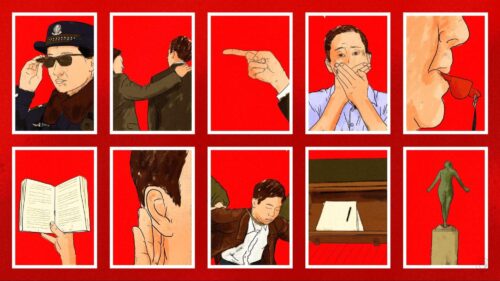

The fate of The Eight Hundred also offers a glimpse into some systematic and administrative changes inside China’s movie censorship apparatus: SAPPRFT still stands at the center, but there are other forces coming into play, and they are politically motivated. “Andrew,” a movie critic on Douban, notes: “The current problems with Chinese movies are not all about traditional censorship. Now it’s more about other forces with influence and interference. They are invisible pressure outside the censorship system,” the critic wrote (in Chinese), adding that after the success of Dying to Survive (我不是药神 wǒ bù shì yàoshén), a 2018 black comedy that tells the real-life story of a man who smuggled affordable but unapproved cancer medicines from India for himself and other patients, SAPPRFT has come under a lot of pressure to beef up its scrutiny. “Since then, movie releases can be easily disrupted by a call, a conference, or a notice that comes from some ‘officials,’ ‘relevant departments,’ ‘professional organizations,’ ‘related people,’ ‘associations,’ ‘religious organizations,’” the critic wrote.

So far, a string of movies has fallen afoul of these “external forces,” as Andrew noted. The release of Better Days, which features violent scenes of campus bullying, was reportedly delayed due to complaints from the Education Ministry. First Man (登月第一人 dēngyuè dìyīrén), an American production that tells the story of astronaut Neil Armstrong, has come to a halt because of objections from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which expressed discontent about the movie’s depiction of the Cold War. And Li Na: My Life (李娜 Lǐ Nà), a biopic of the legendary tennis player, has gone through major delays in production due to negative comments from China’s General Administration of Sport, which still views Li Na as an outlier unworthy of praise because the athlete achieved massive success as a free agent after stepping away from the state sports association.