‘Broken Wings’: Jia Pingwa’s controversial novel explores human trafficking and rural China

Locked up in the cave, the only thing connecting me to the outside world was that one window and its lattice of forty-eight squares, forty-eight beady eyes looking at me.

When Jia Pingwa’s Broken Wings (极花 jíhuā, sometimes translated as The Poleflower) was first serialized in People’s Literature 人民文学, a prominent Chinese literary journal, it was met with muted but nearly universal praise from critics. Consensus seemed to be that it was not one of the author’s era-defining works, but competent and important, and earned praise for its restraint and social relevance.

Broken Wings is uncompromising and brief. It is told from the point-of-view of Butterfly, a young woman who is kidnapped while working with her parents in the city. She is transported to rural Shaanxi and sold as a bride to an impoverished villager, who imprisons her in a cave. Her captor rapes her and she bears his child. The police eventually locate Butterfly and save her from the village, but she is forced to leave her child behind. Not long after, she makes the decision to return to the countryside, though much is left unclear — for both Butterfly and the reader.

When People’s Literature Publishing House put out Broken Wings two months after the serialization, in March of 2016, Jia’s novel reached a larger audience, and he found himself caught in the middle of a literary controversy.

It wasn’t the first time.

Jia weathered the political storms of the 1970s and 1980s, including an offensive launched against him during the Campaign Against Spiritual Pollution 清除精神污染, only to see his 1992 masterwork, Ruined City 废都, tarred as pornographic and banned for nearly two decades. But those days seemed to be behind him. Jia had recovered politically from the infamous ban, taking important posts at the Shaanxi and national levels of the Writers Association, as well as being named a National People’s Congress delegate. A creative second wind saw Jia producing important work, like 2005’s Qinqiang, a sprawling village epic that won the 7th Mao Dun Literature Prize and Hong Kong’s Dream of the Red Chamber Award, and the 2007 novel Happy Dreams 高兴 (translated by Nicky Harman for AmazonCrossing in 2017), which was his most accessible book to date and brought him a new audience. Even Ruined City was quietly unbanned in 2009 (translated by Howard Goldblatt for University of Oklahoma Press in 2016).

Jia has taken chances following that run. There was a Cultural Revolution novel, Ancient Kiln 古炉 (published in 2011, currently untranslated); then The Lantern Bearer 带灯 (2013, translated by Carlos Rojas for CN Times in 2016), which is a record of local government corruption; and then Master of Songs 老生 in 2014, a rural epic spanning six decades, described as “one of Jia’s most obviously political novels.”

Broken Wings goes straight for third-rail issues, too, tackling rural poverty, human trafficking, and family planning policy. It’s a tough read, with frequent scenes of brutality, and no happy ending.

Critics called Broken Wings evil, an endorsement of human trafficking, and a defense of a backwards way of life, while others rushed to the book’s defense. But many of the hot takes flew in response to the book’s afterword (published separately and widely circulated) and Jia’s pre-press interviews.

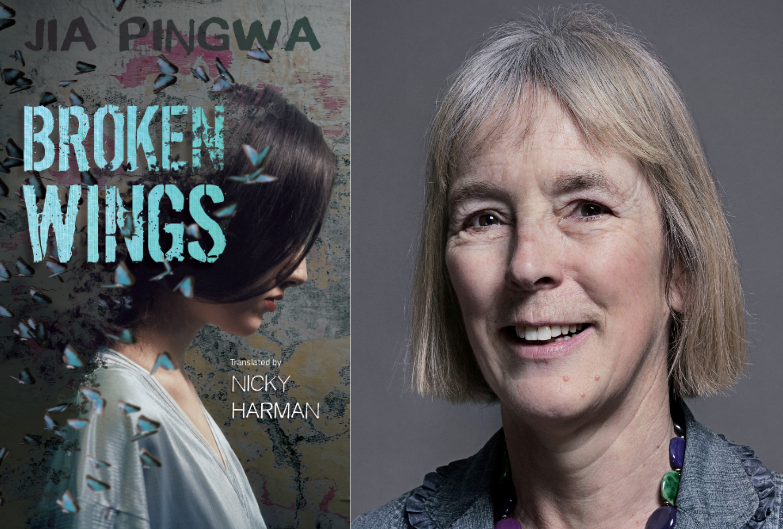

This year, Alain Charles Asia (ACA) commissioned a translation of the novel by Nicky Harman, bringing the novel to an English-speaking audience with far more alacrity than most Chinese books receive. With the novel available in English and the flames of controversy burned down to coals, it seems like the perfect time to return to the issues raised in the debate over Broken Wings.

The germ of Broken Wings can be found in a story told to Jia Pingwa while he was in Southern Shanxi around 2006, visiting his old village: a young woman, who had dropped out of school to join her parents in Xi’an, where they worked as trash collectors, had been kidnapped; she had been sent by her kidnappers to a poor village, where she was sold to a man in need of a wife.

“It took them three years to find her,” Jia writes in the book’s afterword, translated by Nicky Harman, “and with great difficulty they had managed to get the police to rescue her. But now, six months later, she had gone back to the village where she had been taken.”

Jia had heard about cases of women and children being kidnapped in the city and trafficked to poor villages, but he admits that it “felt as remote from my own life as if I was reading a foreign novel about the slave trade.” After coming face-to-face with the reality, and meeting the parents of a trafficked woman, Jia, who roams across the Central Plains to research his books and essays on rural life, was haunted. He saw the kidnapped woman in rural women: “…every time we drove along the ridge-top roads we would come across some woman coming back from digging potatoes, her face weathered and sun-burnt, bent double under the weight of a great basket, hobbling along bandylegged, and I thought of my neighbour’s daughter.”

Jia broke new ground with Broken Wings. Treatments of the topic in film and literature are rare, with the rare exception of Li Yang’s 2007 film, Blind Mountain 盲山, in which Bai Xuemei, a Sichuanese woman, is kidnapped and sold to a villager in rural Shaanxi. The film was recut several times before it was shown at Cannes in 2007, but it never received a domestic release, despite the alternate happy ending Li cut together specifically for that purpose. A 2009 film, The Story of An Abducted Woman 嫁给大山的女人, based on the true story of abducted woman Gao Yanmin, was released, but was criticized for being an overly optimistic take on the issue.

Critics diagnosed Jia with “straight man cancer,” a concept akin to “toxic masculinity.”

In China, despite an admirable attempt in recent years by the central government to crack down on human trafficking and abduction, it remains a serious problem. The issue of child abduction in particular has grabbed headlines, and estimates of the number of children kidnapped each year range as high as 200,000. Chen Shiqu, former head of the Ministry of Public Security’s anti-trafficking bureau, disputed the figure, but even the official numbers he reported were shocking: 54,000 cases between 2009 and 2012. (Not able to make much headway on the file, Chen later attacked judges for lenient sentences and called for the death penalty for traffickers.)

This is not a China-specific problem, either. Human trafficking is a global problem, with more than 40 million people in modern slavery (more than 70 percent are women and girls) in 180 countries, 24.9 million of them in forced labor, and 15.4 million in forced marriage.

Poverty is the motivating factor for vast numbers of people around the world to move in search of work, and that is when women and children are most vulnerable to exploitation and abduction. China has a large floating population (流动人口 liúdòng rénkǒu) — internal migrants from the countryside working in cities — numbering around 250 million. That floating population is particularly vulnerable.

Attempts to explain the prevalence of human trafficking, forced marriage, and child abduction in China inevitably turn to the gender imbalance and “surplus men” created by the country’s one-child policy, which began in 1979 and continued until 2015. That is echoed by a Human Rights Watch report which repeats the bride shortage explanation. The gender imbalance certainly adds pressure, but it’s also worth considering the ongoing economic disempowerment of women and girls, patriarchal beliefs, lack of protection for women in the legal system, and also a political atmosphere that makes it difficult to report on abduction and trafficking. Stories about children and women being trafficked into China are one of the few sources of information on the practice. These reports usually originate in local media, rather than inside China, as in the case of trafficked women from Myanmar, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Pakistan.

Jia Pingwa does not ignore the gender imbalance wrought by family planning policy, the lack of legal protection for women and girls, or a legal system and political atmosphere that can make it hard to raise the alarm, but he points to a more economic materialist explanation as well: 40 years of hyperinvestment in cities and divestment from rural China has killed village society.

“China had 3.6 million villages in 2000 — but only 2.7 million by 2010. In one decade 900,000 villages disappeared, almost 250 per day,” Liu Qin notes in a piece about the novel for China Dialogue. The Party’s rural revitalization strategy has the stated goal of reducing migration from village to city, but the legacy of underdevelopment in the 1990s has proven hard to shake, and it looks as if this will be another campaign of market reforms. The “full realization of farmers’ wealth” has been pushed back to 2050.

As Jia writes in the afterword:

…kidnapping of women and children is brutal and cruel and should be cracked down on. But every time there is a crackdown, the traffickers are severely published and the police are lauded for their heroic rescues, no one mentions the fact that the cities have plundered wealth, labour power and women from the villages. No one talks about the men left behind in the wastelands to wither like gourds on the frame, flowering once, then dying fruitless. These are the last villages in China, and the men are probably the last bachelors too.

“Nowadays,” as Jia explained in an interview, “in most villages, the able-bodied men are long gone. They have left to find work. The same goes for women. … Most of those men that go out of the village for work will probably return, but the women won’t. So, you have village after village of bachelors. … This is a serious problem, but who’s going to help them?”

Critics diagnosed Jia with “straight man cancer” 直男癌 (zhínánái), a concept akin to “toxic masculinity,” used to call out male chauvinist behavior. Jia was charged with promoting a brand of traditional masculinity that has stripped women and girls of rights and freedoms, and a “morbid nostalgia for the countryside” (病态的怀念乡村 bìngtài de huáiniàn xiāngcūn).

A review by Hou Hongbin 侯虹斌 sums up the view of Jia’s critics:

Why will no women marry into a village like that? If a village like that disappears, wouldn’t it be a good thing? Most people can provide an answer: the chauvinistic attitudes of the villagers are oppressive, and the women they could have married were murdered as infants. The men in these sorts of villages are poor, lazy, and debased. Look at Bright Black… He lived off his mother’s hard work, and once she was dead, the two men, in the prime of their lives, were impoverished. Women are no better than beasts of burden. Their life in the village is hell. I don’t know why Jia Pingwa wants to save this kind of village.

“The pure, traditional village” that Hou Hongbin claims Jia is writing about “has never really existed in China’s history.”

Jia’s particular identity — male, cultural elite but a self-identified peasant 农民, in his late 60s — makes it easy for others to paint him as out-of-touch. He has always been closely identified with the horny literary men of novels like Ruined City, and the regressive gender politics on display throughout his oeuvre have not aged well. Jia seems to have softened — perhaps literally — in recent years, with female characters appearing more regularly, like Daideng, a female college student who goes to work as a village cadre in The Lantern Bearer.

It is certainly not wrong to sympathize with rural men who have trouble finding wives. A review by Shen Wenxi 沈文熙 brings up the phenomenon of “wealthy leftover women and poor bachelors” (富剩女穷光棍 fùshèngnǚ qióngguānggùn), or 甲女丁男 (jiǎnǚ dīngnán), women thriving in the city. This is not accurate, of course: women still earn significantly less than men, rampant violence against women and children has not been addressed, and gender equality in politics has a long way to go.

Government policy through the 1990s and early-2000s positioned women as ideal neoliberal subjects, pushing them to move to the city, join the workforce, and delay pregnancy, but traditional ideas of family and masculinity persisted, and the dismantling of the social safety net made it harder for rural families to make a living without the help of their sons. With the household registration system denying rights to rural migrants, marrying for an urban hukou 户口 and staying in the city was often preferable to returning to the countryside.

As Nick Stember writes, “[Broken Wings] isn’t so much a defense of rural villages, as it is an indictment of increasingly irreparable divide between the urban and the rural in Chinese society.” Stember addresses directly the views of Hou Hongbin and others when he writes: “That the villages should just die out or disappear may seem like taking the moral high road, it conveniently ignores the fact that the ‘Chinese economic miracle’ of the last 30 years has incentivized the cheap labor and undervalued agricultural products…made possible by rural poverty.”

Picking up where she left off with Happy Dreams, Nicky Harman has done an excellent job of interpreting the original.

Most readers of Broken Wings in English will not have access to Jia’s pre-press interviews or his reputation looming over the book. Readers of the translation are likely to approach it without much — or any — knowledge of the controversy and the conversation around male chauvinism and morbid nostalgia. Perhaps that will serve to shade the black-and-white conclusions that Jia’s critics have reached, allow shades of gray to filter between the lines, and let the universal themes of freedom and bondage, tradition and modernity, and town and country shine through.

“I didn’t find it morally equivocal [and] the violence is not gratuitous,” Nicky Harman said, addressing the controversy. She pointed to the afterword and Jia’s invocation of ink wash painting as inspiration, and the ideas of liúbái 留白 (leaving blank space) and xiěyì 写意 (to suggest a theme or form rather than depicting it in careful detail):

There are many ways of writing a novel but nowadays it seems to be the fashion to write violent, extreme narratives. Maybe that is what today’s readers want, but it does not suit me. I have always thought that my writing was somehow akin to ink-wash paintings, painting in words, you might say. … The essence of ink-wash painting lies in xieyi, the ‘suggestion’ rather than the detail… That is the core of this art form; xieyi is not concerned either with reason or with unreason. It is truth, not a conceptual idea.

Jia was quick to extend sympathy to rural men in interviews, but when he puts his own argument into the mouth of Bright, Butterfly’s captor, they are undercut by the brutality of the character. “All these new cities the government’s developing,” Bright says, “they’re like giant bloodsuckers, slurping up money and property from the village, sucking away the village girls.” Spoken by a man we know to have purchased another human, it’s hard to take the argument quite as seriously, and Butterfly is waiting in the next paragraph to offer her own counterargument.

The voice of Butterfly carries the novel. It is impossible not to sympathize with her. She is a tragic figure, a village girl herself, whose hopes and dreams are crushed.

Butterfly is thriving in the city when a man approaches her about a job:

He told me to report to the Sheraton Hotel the next day. I never told my mum, I wanted to surprise her by earning a ton of money. The next day after she left to go trash-picking, I got ready. … He took me into a room, where there were half a dozen other girls, but none of them as pretty as me. They all had migrant worker parents too. They asked me where I was from and I said from the south side of the city. They were impressed with my high heels, and I let them try them on, but their feet were either too big or too fat. Definitely not born to be city girls.

When she boards the bus, she is drugged and taken to a remote village:

There were rats in the cave, gnawing at the old chest. They never gave up even though there was no grain in it, only a heap of rags and some old cotton waste. … I wasn’t going to get up to scare them away, what the hell, they could carry on gnawing for all I cared, let them gnaw the chest into bits, let them gnaw the darkness to bits for me

One night about six months ago, I made the first scratch on the cave wall with my fingernail. Since then, I’d added a scratch each day. … [A]ll I had to show for the last six months of my young life was a few scratches. When I made the one hundred and seventy-eighth scratch, I was so humiliated and furious and distressed and helpless that I dug my right index finger in too hard, broke the fingernail and made it bleed. I wiped the blood off on the poster girl.

The scenes of Butterfly and her son, Rabbit, are particularly moving:

It suddenly occurred to me that my baby should be called Rabbit, because when the goddess Chang’e was all alone on the moon, she had a rabbit to keep her company. I cuddled him and kissed him: “Rabbit, Rabbit.” …

“Fine, ‘Rabbit’ it is then,” Bright conceded. “That’s a good name too. How long before Rabbit says ‘Dad’?”

He’ll only say ‘Mum’, I said silently. I looked at the ceiling of the cave, though I couldn’t see it, only blackness. I popped Rabbit’s little foot into my mouth again, it was like a sugar lump, ready to dissolve, then I took it out of my mouth. Rabbit, you listen to your mum, one day Mum’ll take you to the big city, we’re not staying in this desperate place.

I had the feeling that the world had shrunk around me till the world was only me, and I was a spirit here in this village, in this cave.

Hou Hongbin charges Jia with attempting to write about a “pure, traditional” village but that is not the impression the reader is left with. The village setting of Broken Wings is horrifying; the villagers are illiterate, unwashed, and brutal. Butterfly speculates: “‘Well, maybe the whole village is poisonous … Just look around you, people get robbed, there’s bare-faced cheating, there’s troublestirring, greed, jealousy, quarrelling and scamming.’” To her, the villagers are no better than beasts: “…there were tigers and lions, and centipedes and toads and weasels, then there were clouds of bluebottles and mosquitos.”

“The description of the rape is horrific,”says Nicky Harman, the book’s translator. “There’s widespread casual brutality (at least one of the kidnapped wives gets her leg broken when she tries to run away) and the atmosphere in this village of home-prisons is suffocating.”

When Butterfly is finally rescued by the police and her mother, life in the city is not much better. The police are heroic, eventually, though they admit that they usually get reimbursed for finding kidnapped women and children. The journalists who come to ask her about the experience want to know “how poor and backward and uncivilised” the village was, if her captor was a “cripple, ugly and dirty,” and whether or not her child was born with a harelip. Neighbors arrive to ask even less polite questions.

When Butterfly makes the heartbreaking decision to return to the village, she knows that she is delivering herself back into the desperate situation that she recently escaped from. Life in the village, as horrible as it might be, is preferential to life in the the city, where she is marked as the victim of kidnapping and rape, and separated from her Rabbit.

Jia’s reputation as one of the greatest living authors is hard to dispute, but his prose often comes across as turgid or overly dense in the hands of less skilled translators. Picking up where she left off with Happy Dreams, Nicky Harman has done an excellent job of interpreting the original.

The problem with translating Jia Pingwa lies in his mixing of high and low — classical allusions are set down beside scatological dialect expressions, and poetry flows alongside earthy descriptions of village life. Harman’s Pierre Menard-like devotion to understanding the text kept her in close contact with the author, and even saw her touring cave homes in Northern Shaanxi. Her understanding of the book, her excellent writing, and confidence in her abilities have produced a translation that preserves the spirit of the original while being able to stand on its own in English.

Broken Wings, appearing three years after the publication of the original novel, is a rare treat, which can be credited to a renewed interest in Jia Pingwa’s work, as well as ACA CEO Wang Ying being a keen reader of contemporary fiction. (It was 23 years after Ruined City’s original publication and seven years after it was unbanned before Howard Goldblatt’s translation was commissioned by the University of Oklahoma Press.)

Early translation, Nicky Harman says, “enables Western readers to follow an author’s development, and see where she or he is heading in terms of themes and style. Three or four years ago, Jia thought that human trafficking was an important topic to write a story about. It’s still important, and that gives the English translation an immediacy.”

Broken Wings, by Jia Pingwa, translated by Nicky Harman, is available on Amazon.