‘Cities of Last Things’: A revenge story told backwards in a hodgepodge of genres

A three-part film told backwards, defying style and convention: Cities of Last Things is the first in our series of reviews of Chinese movies currently available on Netflix.

Even in our age of instant rentals and endless streaming services, keeping up with Chinese-language film can be a frustrating ordeal abroad. Some movies might take a year or longer to hit the United States outside of limited screenings, others might never see an official release at all. The past year or so, Netflix has tried to fill this void by expanding its Chinese-language content. The streaming giant has released box office hits like Us and Them 后来的我们 and The Wandering Earth 流浪地球 mere months after their Chinese opening days, while also cultivating more indie, critically-acclaimed fare, like Taiwan’s gay-themed drama Dear Ex 谁先爱上他的.

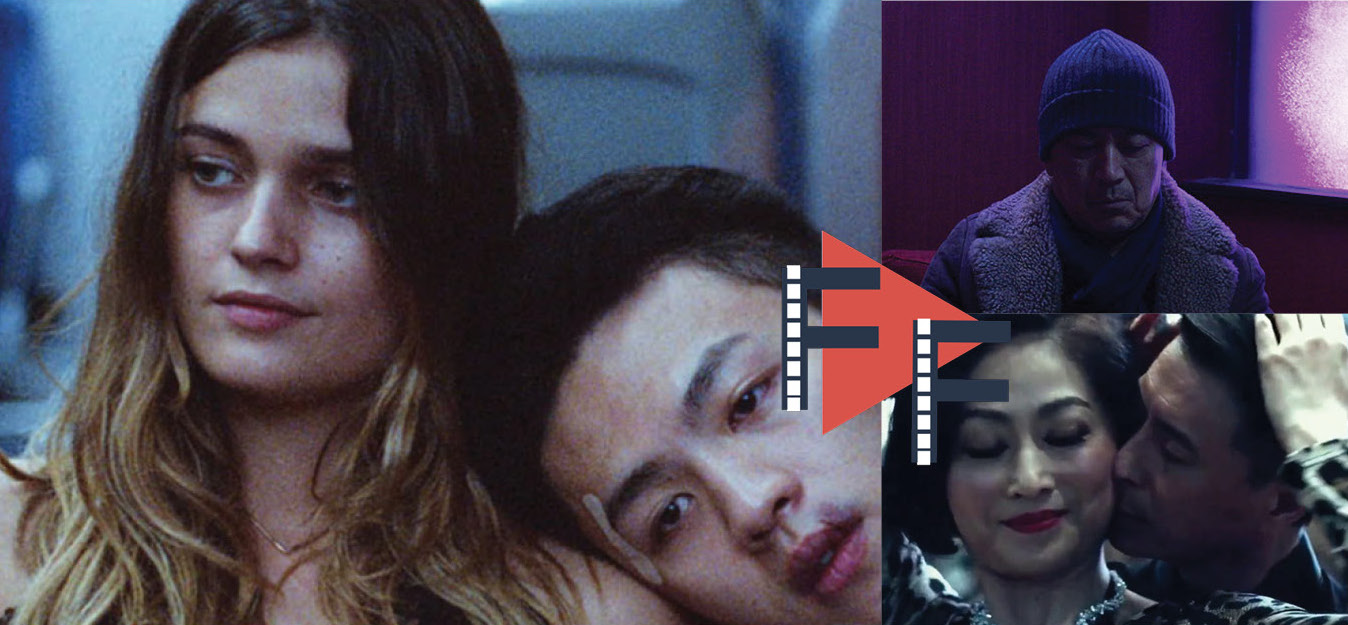

Netflix’s latest addition from Taiwan is Cities of Last Things 幸福城市, a hodgepodge revenge tale from Malaysia-born director Ho Wi Ding 何蔚庭. The movie combines various genres, following the life of a man named Zhang Dong-ling across three life-changing, irreversible nights. Its story unfolds backwards. Reverse chronology can be a risky and even pointless gimmick, but Cities of Last Things manages to pull it off without being annoying.

The first segment plays as a sci-fi dystopia, with all the usual bleak and dark imagery. We encounter Dong-ling as a bitter elderly man in the year 2049, walking past the aftermath of a grisly suicide. While a crew of men clean up the scene, a PA system implores onlookers to stay positive, announcing in a monotone that “It’s wrong to kill yourself.” The Taiwan of the future is a lonely, closely monitored place. Buses drive themselves, white drones patrol the skies, and money and pensions are dispersed through thumbprints. Older people enjoy anti-aging drugs, while the younger generation looks for hope abroad.

As Dong-ling makes his rounds that night, he hits up a brothel, visits his daughter, and takes revenge on three people who have wronged him. The first is a politician whose connection to Dong-ling isn’t immediately clear. The second is his wife Yu Fang’s lover, while the third is his wife herself. What did these people do to make Dong-ling so angry, and why does he feel the need to be so merciless? It’s a slow introduction, but it provides enough intrigue to want to understand a lead as initially unsympathetic as Dong-ling.

After some 40 minutes, the movie shifts into its second episode, a noirish romance in the present day. Dong-ling is a policeman, happily married and with a promising career. While doing his beat, Dong-ling chases and arrests Ara, a foreign kleptomaniac. It seems like an ordinary and inconsequential day, but then Dong-ling stumbles into a secret involving his wife that triggers a chain of unhappy consequences. At one point, he’s beaten and almost killed on the street until Ara reappears and the attackers run off. The events of the night bring the two closer, but Dong-ling doesn’t make it out any happier due to forces beyond his control.

The final segment, a family drama of sorts, is the shortest. It centers on Big Sis Wang, a gangster who’s brought into police custody the same night as a teenage Dong-ling. Dong-ling is accused of stealing a scooter, but concocts a story that he thought it belonged to a nameless, unreachable ex-girlfriend who’s conveniently in Thailand at the moment. The real reason behind Dong-ling’s theft sparks a surprising conversation with Big Sis Wang, and leads to a powerful revelation of why Dong-ling becomes the man that he does.

The genre-dabbling and non-linear structure of Cities of Last Things makes it an interesting experience. Each of the segments has its own aesthetic and mood. The first, a snowy dystopia, is brutal and cold. The second, set in the summer, is faster-paced and more expressive with its romantic subplot. Confined largely to a police station, the third proves to be claustrophobic and heartbreaking. A short vignette at the end, depicting Dong-ling as a child, is bright and nostalgic, but undeniably sinister in lieu of the rest of the man’s life.

Although the three different segments build upon each other well, this mishmash can be uneven. In contrast to the conciseness of the third segment, the other two are sometimes meandering. It also doesn’t help that, with a backwards plot, some scenes can’t help but feel confusing or clunky until later scenes clarify their relevance. Still, had Cities of Last Things taken a more linear approach, I don’t think it would have been as satisfying. Dong-ling appears all the more tragic with this reverse structure, amplifying the feeling that his life couldn’t go any other way.

While it doesn’t look entirely correct or complete, most of the movie’s puzzle pieces end up fitting in the right places. Cities of Last Things is a wonderful addition to Netflix’s catalog, and I’m eager to see what else the company plans to bring over this year.

Film Friday is The China Project’s film recommendation column. We’re currently featuring Chinese films available on Netflix. Have a recommendation? Get in touch: editors@thechinaproject.com