Why Chinese are good at math (and it’s not racial)

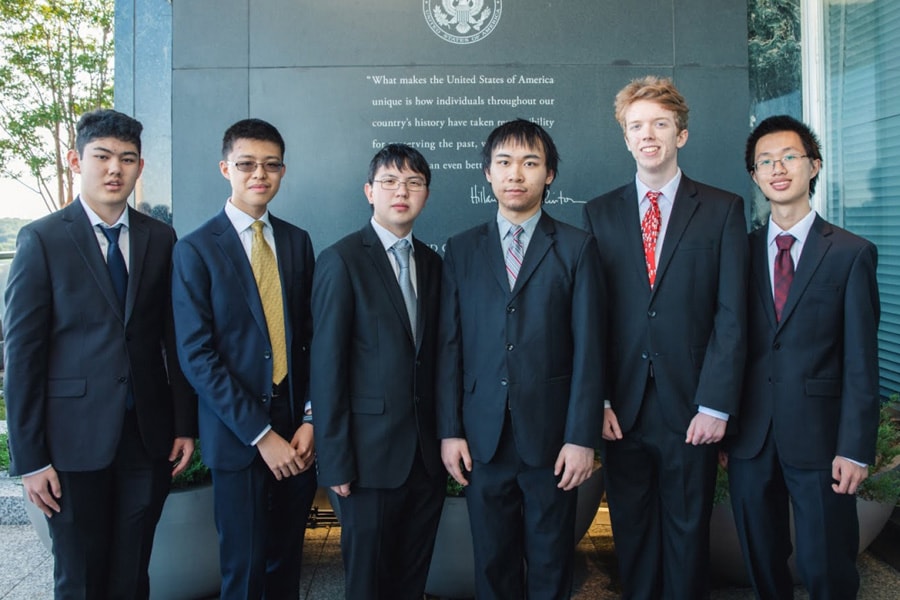

China and the U.S. were co-champions of the 60th International Mathematical Olympiad, held last month at the University of Bath in England. Five of the six competitors on the American team were of Chinese descent.

This week’s Kuora comes from one of Kaiser’s answers originally posted to Quora on May 10, 2015.

Why do so many winners of American math, science, and spelling competitions have ancestry from China or India? What is a good explanation for the academic dominance of Chinese and Indian students?

I’ve thought often about this question. I’ll say first that I do not believe in ethnic or “racial” explanations for the observation, which I believe is (we can confidently accept) empirically verifiable.

Most of it, I think, owes to a kind of selection effect in the process of emigration/immigration. China and India are both enormously populous countries (India about 1.2 billion, China about 1.35 billion), and countries from which emigration to the U.S. is not by any means trivially easy. There are a lot of competitors for a limited number of slots. Those who are successful tend to be people who are willing to make significant effort to better not just their own lot in life, but their children’s lot in life as well. Most Chinese I know, at least, who do emigrate do so primarily for their children and future generations. They’re willing to tear themselves away from friends and family and the surety and safety of a social network, learn a second language, and endure in some cases bigotry and racial prejudice. While I’d hesitate to say that these are the “best and brightest” of India and China, they’re certainly not the run of the mill of either country.

Educational, professional, or artistic attainment, or success in business (read: wealth) all significantly help one’s chances of being granted immigrant status. Of these, education is almost certainly the biggest factor. Huge numbers of Chinese and Indians who have emigrated to the U.S. in recent decades have done so for postgraduate education, often in STEM areas. So basically you have a group of immigrants dominated by those self-selected for academic performance. It’s not at all far-fetched to suggest that they’ll tend to prioritize academics with their own children. Not all of course go to the U.S. for graduate study. But in the rest, I’d wager you’d find other traits that probably positively influence their children’s competitive spirit: low aversion to risk, ability to defer gratification, strong work ethic, etc.

Having (in some cases) done graduate study in the U.S., these parents will tend to find work in tech companies, in finance, in academic research, or other areas that will put them not just in socio-economic but also geographic proximity to the American upper-middle class, and occasionally beyond. These are demographies that pay high property taxes, meaning good (read: competitive) schools. These schools will then only accentuate the likelihood that a given kid will participate in the kinds of competitions — math, science, spelling — that the question asks about.

So to sum up so far, Chinese and Indian students will be highly represented at the best American schools in large measure because barriers both to emigration and to immigration tend to select for certain types of success from very populous Asian countries, and immigrants from those countries will seek to replicate in their children the same advantages they believe enabled them to emigrate and immigrate.

Of that part I’m fairly confident. But I believe there’s more. I don’t know much about Indian pedagogical traditions, but I know that in the case of Chinese educational norms, there’s a great deal of emphasis on rote memorization. In fact, because written Chinese only offers very partial clues to pronunciation (unlike alphabetic or syllabary-based languages), even attaining basic literacy involves a great deal of memorization. It might be a stretch to suggest that this process “hard-wires” children for other mnemonic tasks, but I think that half-baked hypothesis might be worth a good study. In any case, having watched my own kids go through grade school in Beijing, I’m struck by how much memorization goes on: Multiplication tables up through the 20s, squares and square roots, long lists of prime numbers, poems running to over a hundred lines (yes, they’re short, three-character lines — but they were doing this at age 4!).

I remember seeing studies that show that the academic advantages shown in second-generation immigrant families from East and South Asian countries in America fall off quite precipitously in subsequent generations, suggesting that the really salient factor here is the influence of the immigrant parent(s).

Kuora is a weekly column.