‘A City of Sadness’: Hou Hsiao-hsien’s historical tragedy remains a masterpiece 30 years later

The first Chinese-language film to ever win the Venice Film Festival’s Golden Lion award, Hou Hsiao-hsien’s A City of Sadness is the story of three brothers during Taiwan’s “White Terror” period following World War II, when the island was under martial law. The film is a powerful, timeless piece of art.

Internationally, Taiwanese director Hou Hsiao-hsien (侯孝贤 Hóu Xiàoxián) is one of the most well-regarded filmmakers to come out of the Chinese-speaking world. Since the 1980s, Hou’s work has been showered with awards both domestically and abroad, including a Best Director award from the Cannes Film Festival for his most recent movie The Assassin (刺客聂隐娘 cìkè nièyǐn niáng) (2015). His 18 feature films generally touch on Taiwan and its history, and are distinguished by long shots and a stationary camera.

Hou’s ninth feature, A City of Sadness (悲情城市 bēiqíng chéngshì), celebrates its 30th anniversary this year. This historical masterpiece, showing the effects of the infamous White Terror on a Taiwanese family, is a landmark for several reasons. When A City of Sadness premiered at the Venice Film Festival on September 4, 1989, it was considered an achievement alone that a Taiwanese movie was able to run in the competition. Hou and his team scarcely imagined that their film would take home the festival’s Golden Lion award, the first Taiwanese (and Chinese-language) work to do so.

Aside from its critical prestige, A City of Sadness is also notable for the political taboos it broke in Taiwan. When Japan returned Taiwan to China in late 1945, many Taiwanese felt optimistic about being reunited with the mainland. Under the corrupt rule of Kuomintang general Chén Yí 陈仪, however, their enthusiasm quickly waned due to rapid inflation and other economic problems. Tensions between the new government and the Taiwanese came to a head with the February 28 Incident, when riots broke out after government agents beat a cigarette vendor and shot a civilian in Taipei.

The Kuomintang responded to the uprising harshly, arresting, beating, and shooting protesters. To this day, an exact death toll has never been established. Thousands of people are thought to have died in the massacre, and some estimates put the total number of victims even higher, between 10,000 and nearly 30,000 deaths. After the Kuomintang relocated to Taiwan as its base in 1949, martial law was declared across the island. During this “White Terror” period, political dissidents were arrested and executed, and it wasn’t until 1987 that martial law was finally lifted.

In this atmosphere of political repression, discussions about the February 28 Incident and the White Terror were forbidden. With the end of martial law, A City of Sadness became the first movie to focus on this tumultuous era of Taiwan’s history. At the time of the movie’s production, there were few books and reports about the incident that Hou and his team could access. The Guangdong-born Hou and his native Taiwanese screenwriters Chu T’ien-wen (朱天文 Zhū Tiānwén) and Wu Nien-jen (吴念真 Wú Niànzhēn) were all born after the massacre, so relying on their own experiences was out of the question. For historical research, the filmmakers had to pour over interviews, diaries, letters, and government documents to get an idea of the period.

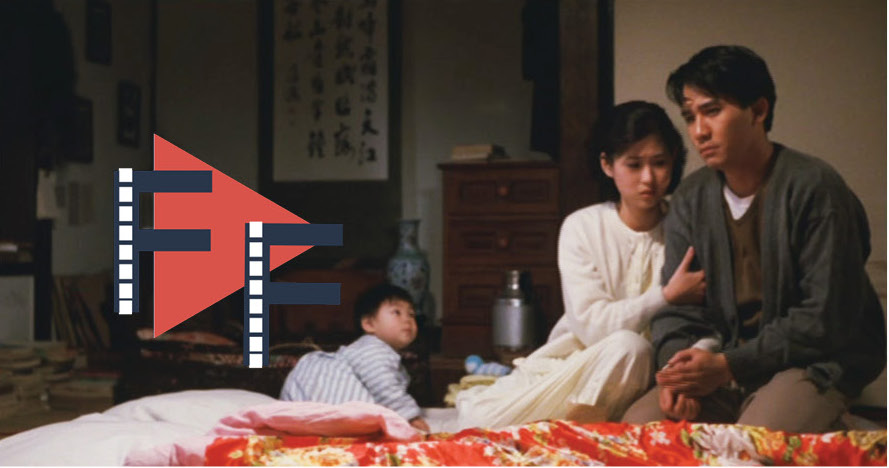

Rather than showing the incident through dramatic, massive scenes of marching, fighting, and protesting, the center of A City of Sadness is smaller, concentrating on the fictional Lin family and their four sons. The oldest, Wen-heung, owns a bar. The second and third sons, Wen-sung and Wen-leung, were drafted into the army during World War II. Wen-sung has vanished in the Philippines, but Wen-leung returns troubled and mentally ill. The youngest, Wen-ching, is a deaf photographer who associates with an intellectual, left-wing circle. Each of the three surviving brothers have their own subplots, their stories twisting and intersecting as Taiwan grapples with Kuomintang rule.

On its release in Taiwan, A City of Sadness was attacked by some critics for not going far enough with its depiction of February 28. While the incident might provide a backdrop, the movie’s presentation is largely subtle and elliptical. Several characters complain about Chen Yi, for example, but the man himself is only heard on the radio, sugarcoating the monstrosities outside. Bands of soldiers are only briefly seen attacking people, and other pivotal scenes happen off-screen, as when one main character is shot and killed by the Kuomintang. Other bits of important information are related in notes and letters, or voice-overs by Wen-ching’s love interest.

While it had its fair share of critics on both the left and the right, A City of Sadness proved to be a surprising box office success. It made its budget of approximately $1,000,000 back in Taipei alone, and according to one count, half of Taiwan ended up seeing the movie. At the end of the year, in December, it earned two prizes at the Golden Horse Awards, a move that was seen as a political snub by many admirers. Domestic critics have since warmed to the movie, and Hou later directed two more historical-themed pieces that form a trilogy with A City of Sadness: The Puppetmaster (戏梦人生 xì mèng rénshēng) (1993) and Good Men, Good Women (好男好女 hǎo nán hǎo nǚ) (1995).

Long after its controversy and political novelty have worn off, A City of Sadness has endured as a classic. It’s sometimes the case that movies about a tragic historical event can come across as exploitative or sappy, overwhelming the viewer with graphic carnage and cheap, melodramatic moments. By focusing on the personal and subtle, A City of Sadness conveys the disillusionment and despair of its subject’s victims far more effectively than if it devoted itself to scenes of cartoonish bad guys firing into anonymous crowds. It’s this focus on little, ordinary people, rather than giant historical figures and events, that makes A City of Sadness such a beautiful, powerful work of art.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Aolv8k99ZOU

Film Friday is The China Project’s film recommendation column. Have a recommendation? Get in touch: editors@thechinaproject.com