Wu Guanzhong at 100: Looking back on the life of China’s master painter

Combining techniques from the East and West, “the father of modern Chinese painting” created a style distinctly his own.

Wú Guānzhōng 吴冠中 was born 100 years ago in Zhakou township in Jiangsu Province. The son of a schoolteacher from the rural wetlands, he trained to paint in the hallowed art colleges of Paris and Hangzhou before being re-educated in the remote reaches of the Chinese countryside. He endured a grueling life, but by his death in 2010, he was celebrated as one of the most important Chinese painters of the 20th century, the father of modern Chinese painting, a genius who synthesized the styles of the East and West.

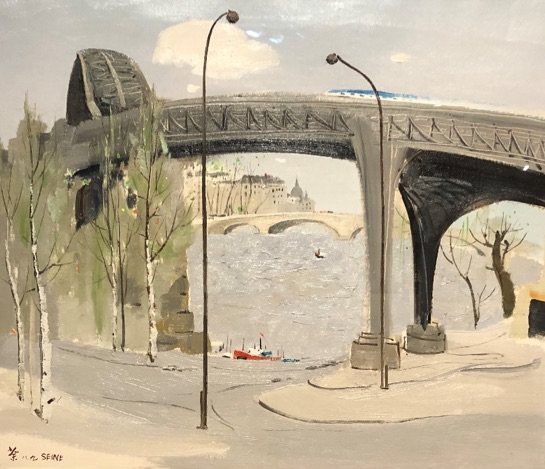

Wu mastered the use of meticulous “French” oils and the sparing, loose brushstrokes of Chinese inks. He was as comfortable painting the Seine River of France as the Huangshan Mountains of Anhui, the loess plateaus of Gansu, or the vast expanses of the African Sahara. To own one of his works is to own a piece of history: In recent years, his most valuable works, both depicting the Jiangnan water villages of his youth, sold for $30 million and $16 million. But his legacy goes deeper. Today, Chinese painters can thank him for his advocacy of abstract art within the Chinese tradition, which he once described as “his life’s work.”

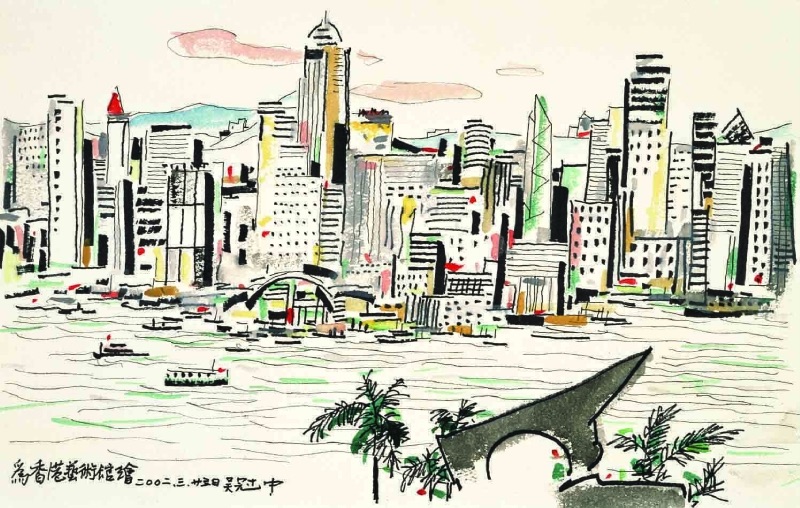

Moreover, his lucid writings on art theory remain significant contributions to the art world. In the firm belief that art should be accessible to all, Wu had a habit of donating valuable pieces to museums around the world, where they now remain readily viewable. This was a tradition most recently continued by his son, Wú Kěyǔ 吴可雨, who donated more than 370 of his father’s paintings to a dedicated Wu Guanzhong Gallery at the Hong Kong Museum of Art last year.

Nowadays, Wu’s art is celebrated and accessible across the world, and the pride of a country. But believe it or not, there was once a time when he was scorned for failing to represent the masses.

Born into a peasant family, Wu’s initial university study was in electrical engineering — a noble profession in a China seeking to rebuild and modernize for the 20th century. Later, however, on meeting Chu Teh-Chun, who would go on to become a world-famous abstract painter, the appeal of art proved too great, and Wu transferred to the famous Hangzhou Academy of Fine Art, where he studied under modern artists Lin Fengmian and Pan Tianshou.

When war with Japan broke out in 1937, Wu moved with the rest of the academy — and indeed much of the Chinese artistic and intellectual communities — to the wartime capital of Chongqing. There, he grew closer to Lin, who studied at the prestigious National School of Fine Arts in Paris and was an early progenitor of Western painting techniques in China. Lin would become Wu’s lifelong mentor and friend.

From Lin, Wu got a desire to hone his art in France. In 1947, after several years dutifully studying the French language, he received a government scholarship to study in Paris. It was during this time that his fascination with Western art concepts blossomed. He developed a keen interest in the great European abstract painters Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Piet Mondrian, and Joan Miro, and the impressionists Camille Pissaro, Paul Cezanne, and Vincent Van Gogh

Wu lamented, however, that terms like “school” and “tradition” kept artistic movements confined to their own circles. He was particularly annoyed by the idea that these abstract masters were abstract masters alone, and that their innovations could not influence painters working in other fields or countries. More specifically, that they shared nothing with painters in China.

To Wu, artistic inspiration — and the innovations that resulted from it — could never exist in a vacuum, and “expressionist” or “abstract” techniques should not be restricted to their corresponding schools or traditions. Rather, they should be at the disposal of all artists.

As he would later write, “Certain kinds of theme bestow upon people common sensations and elicit similar techniques of expression. Thereupon the school of ‘whatever’-ism is born and they are restricted into their set categories. Of our own country’s traditional paintings there are more than a few that look like the Impressionist school, or the Fauvists or whatever. East and West both discovered the commonality of the laws of painting.”

Perhaps the most important development in Wu’s art during his time in France was the beginning of his love affair with what he called “formal beauty.” Developing his already heartfelt conviction that art should not be confined to schools or categories, Wu came to believe that the true source of aesthetic pleasure in a painting lay in the “forms” it depicted. These forms could be interpreted exactly for a realist image, or abstracted, to create an image somewhere between reality and the more abstract image in his mind.

For Wu, these “forms” existed in all paintings — even the most abstract — and it was the aesthetic value of this form that mattered, not its origin or creator. This placed Wu in a unique position within the artistic circles of 20th-century China, which had long grappled with an identity crisis. Intellectuals in all fields felt the need to “change”; indeed, the May Fourth Movement urged the formation of a new China with new sciences, new ideals, and new philosophies. In the artistic world, these debates continued throughout the tumultuous 20th century. A key point of contention was whether traditional Chinese painting (国画 guóhuà), increasingly seen as turgid and backwards, could be saved, and if so, how.

Another great Jiangsu painter, Xú Bēihóng 徐悲鸿, had, in an infamous 1929 essay, argued that Chinese painting could be sustained only with injections of influence from European romanticists like Pierre Pru d’Hon and Eugene Delacroix, and that making use of anything more modern was “no better than importing morphine and heroin.” Innovators like Wu’s mentor Lin Fengmian, however, looked to the avant-garde, seeking inspiration in German expressionists Erich Heckel and Emil Nolde. A further group of guohua advocates, including Pan Tianshou and Fu Baoshi, believed Chinese painting could be reinvigorated and modernized from within its own tradition, and needed little, if any, foreign interference.

Wu was part of the next generation of artists who would lead this debate into the second half of the century.He was disdainful of the notion of “schools” of painting and had long excused himself from participating, but he was a patriot. “I am a Chinese painter,” he explained. “When I pick up the brush to paint, I paint a Chinese picture.” And, evident in his lifelong penchant for painting his Jiangsu birthplace, Wu wished, more than anything, to do justice to his Chinese home.

In a telling anecdote about his time in France, he recounts how, on a late-evening trip to the Louvre, he let loose on an idle security guard who struck up a conversation with the solitary Wu.

“I bet your country doesn’t have art like this!” he said, pointing at the Venus de Milo.

As Wu relates, he was at the time “too sulky” to find a tactful way out of the conversation. He retorted angrily: “Is art really ‘yours’? It’s Greek, stolen away by bandits. You [French] stole our motherland’s art as well. How do you think the Musee Guimet’s Chinese-carved stone heads got there?”

For all its artistic bounty, Wu never felt truly at home in France, as a Chinese guest learning from French masters. And so, unlike the two classmates he traveled to France with, Zhao Wou-Ki and Chu Teh-Chun — who would both become phenomenally successful Chinese-French artists — Wu decided to return to China in 1950, to throw himself into the construction of New China.

New China, however, was resistant to Wu’s synthesis of East and West, and of his increasingly abstract works. While he was allowed to teach, Wu was repeatedly demoted, and his posts became increasingly obscure.

By 1966, with Mao Zedong sending the youth of the nation into an iconoclastic fervor against all things “old” and “bourgeois,” Wu was sent down to the countryside to work on a farm. He was banned from painting, and was regularly beaten, insulted, and paraded through the village in a white dunce cap. Wu, like his mentor Lin, later wrote of the heartache he endured when forced to destroy large numbers of his politically unacceptable works. Remarkably, however, he remained unbroken by the experience, seeing it as an opportunity to learn from his rural hosts, noticing in them an “unaffected aesthetic judgement” — the very unadulterated appreciation of formal beauty that he so admired.

Unlike other artists, who either fled from or adapted to the ideological strictures imposed on them, Wu refused to alter his style, and continued to paint his characteristic colorful-yet-sparse landscapes throughout the Cultural Revolution, often on old pieces of wooden board found around the farmland. It was not until the latter days of the Cultural Revolution, particularly after the death of Mao, that his rehabilitation began in earnest.

As China liberalized in the 1980s and 90s, Wu made frequent trips to Hong Kong and reunited with his mentor Lin, who moved there after spending much of the Cultural Revolution behind bars.

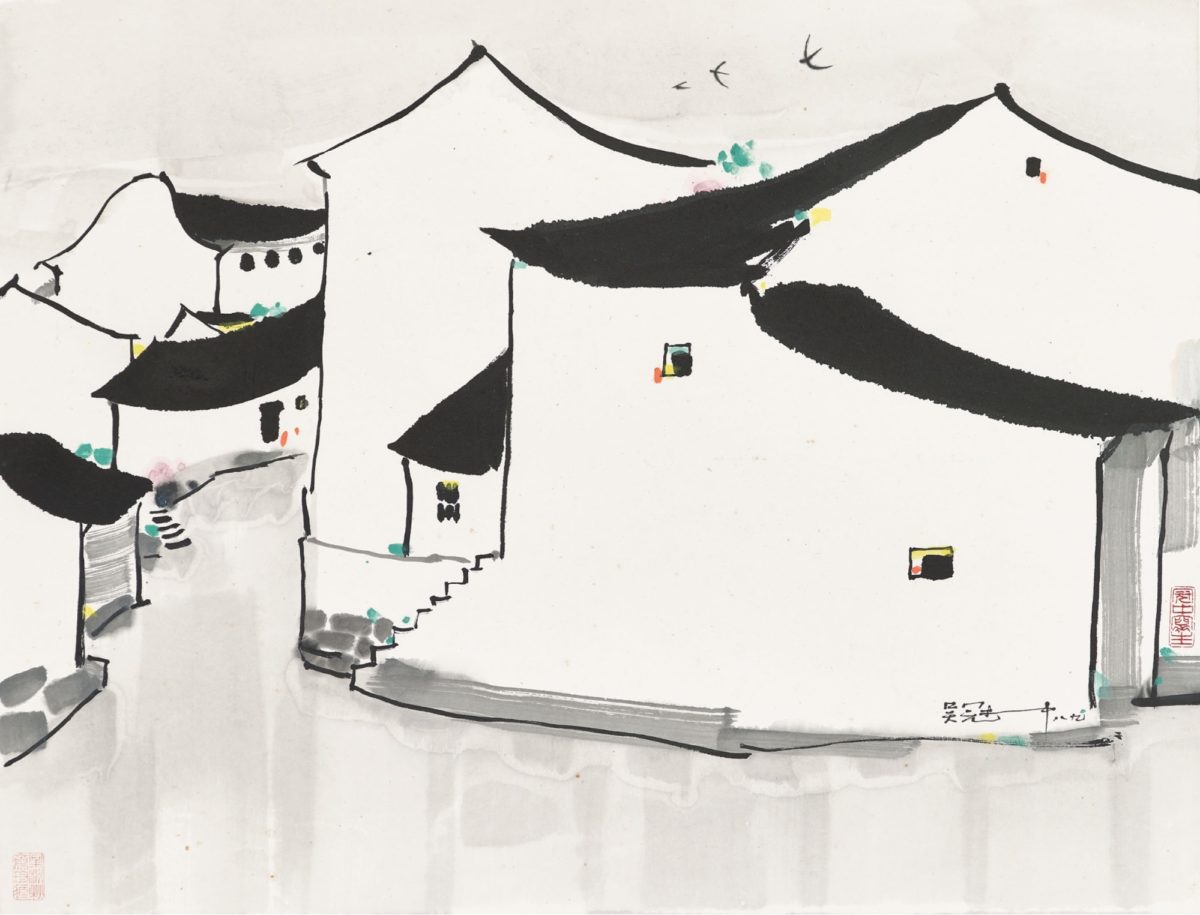

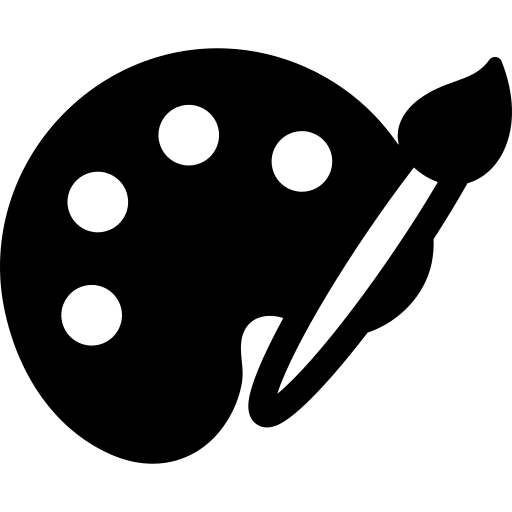

In the late 80s, in exhibitions in Hong Kong and southern Chinese cities like Shenzhen, Wu finally began to receive the acclaim he deserved. The above painting, currently on display at the Shenzhen Art Museum, was exhibited at the Shenzhen Fine Arts Fair in 1985, one of the first international art exhibitions held in China after the start of the reform era.

By 1992, Wu became the first Chinese artist to hold a solo exhibition at the British Museum, showing works like “Paradise for Small Birds” (1989):

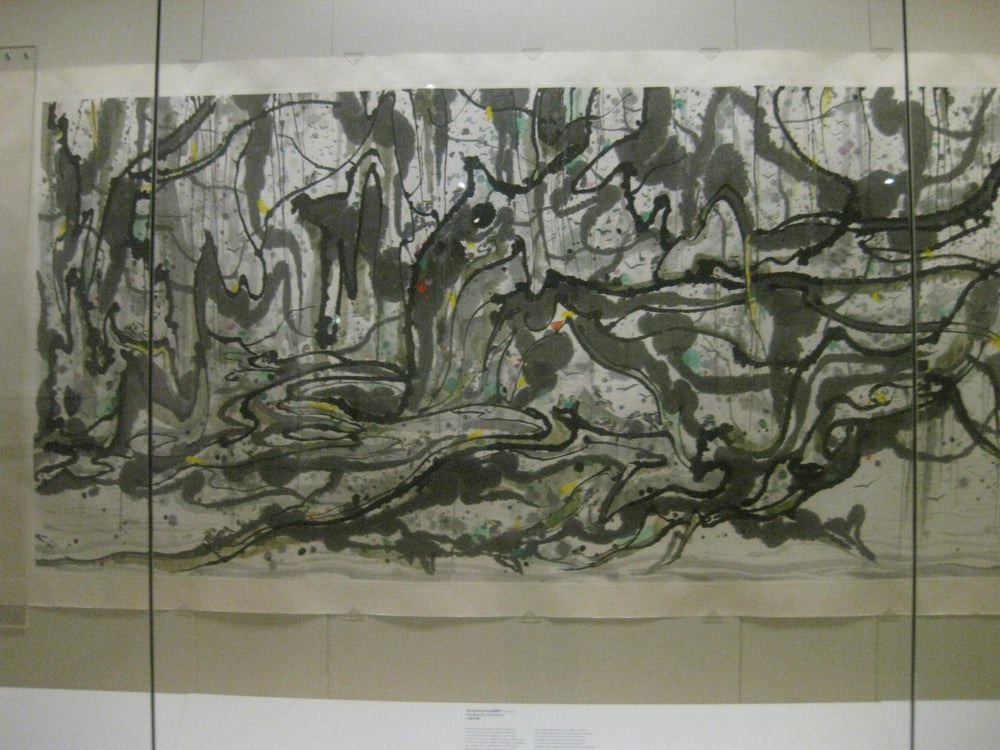

In southern China and Southeast Asia, his works began to sell, too, and much of his work can now be found at museums, galleries, and collections in Singapore and Hong Kong:

While Wu’s earlier oil paintings remain popular, it is his ink-on-paper Jiangnan landscapes that are most valuable.

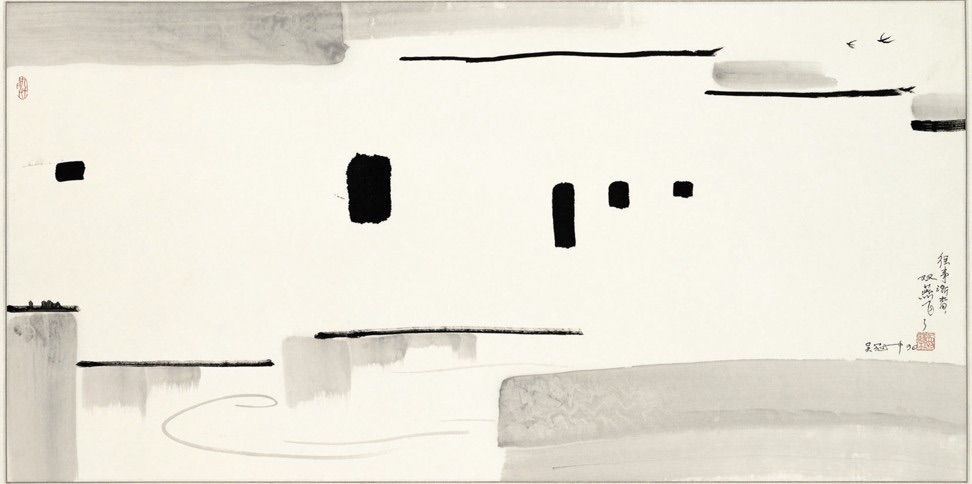

He wrote of his 1981 ink painting “Twin Swallows” (header image), which last December sold for 54 million RMB ($7.5 million): “Of all my works depicting my beloved Jiangnan, and indeed of my entire corpus, it is Twin Swallows that I consider the most expressive, the most outstanding.”

The interplay of heavy black shapes and sparse white walls demonstrate Wu’s penchant for “semi-abstracting” from reality. As he wrote, “Between the horizontal long lines, white blocks and vertical short, black blocks strong contrasts take form…but this practically abstract geometric composition and touchingly entangled complex of features all stem from non-abstract forms.”

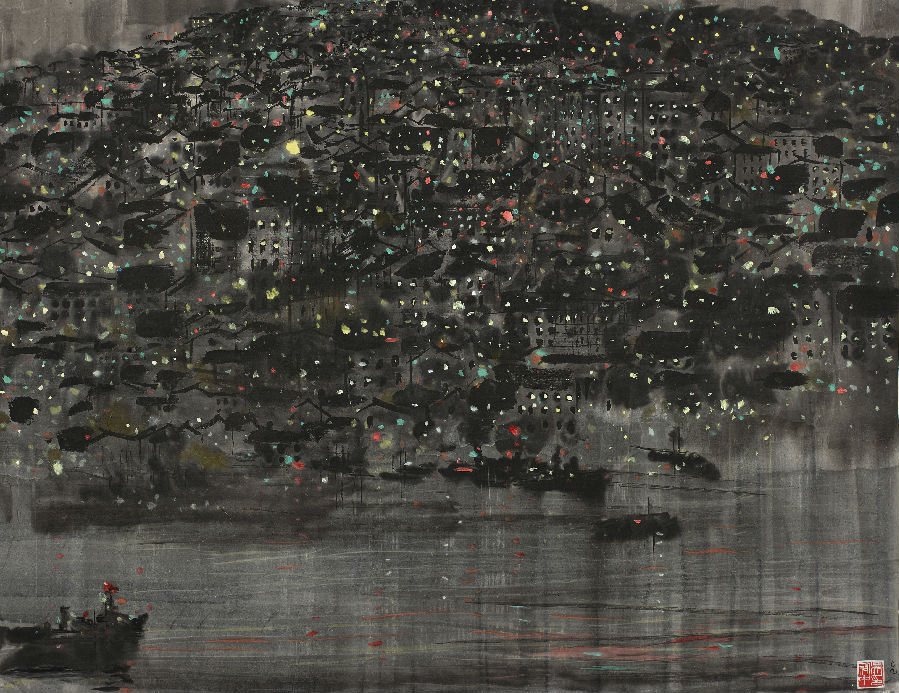

And although he progressed further into the realm of the abstract in later works, such as his 1997 Pollock-esque “Wild Vines with Pearls Like Flowers,” it was here, at the juncture between perceived reality and abstract interpretation, that he was most comfortable, and most celebrated.

In the most general sense, Wu set himself apart from his contemporaries with his lack of concern about the ‘Chineseness” or nationalism of his art. And yet, in doing so, Wu created a new face for Chinese art, one that was not confined by the labeling and quarreling of art theorists, nor the nationalist concerns of guohua painters.

Instead, he created an undeniably “Chinese” form of art that stood, proudly, on its own.

For a man who was once scorned for his failure to represent the masses, it is the ultimate triumph. In the early 1980s, after mentioning him in a lecture in Hong Kong, renowned art historian Michael Sullivan received a letter from Wu. In it, he wrote, “I hope you are able to see my original works from the last few years. I also hope dearly that they may be exhibited in Europe and America, and to see whether my works, for which I have forgotten several decades of sleep and sustenance, will be able to enact a link between the fine cultures of the east and west.”