A modern myth — and a story of modern China

This is the story of a stone.

It is three meters high and seven meters wide, more boulder than pebble, sitting on a riverbank in the southwestern province of Guizhou.

This stone may seem like an ordinary piece of Permian limestone, but as will be revealed, this stone is anything but ordinary.

For you see, upon this stone, the Chinese Communist Party claims 270 million years of history.

And upon this stone, the Chinese Communist Party, it is said, will “perish.”

On June 26, 2002, Wáng Guófù 王国富, at the time a village secretary for the Party, stumbled across a curious rock formation while clearing a scenic area after a photography exposition near Zhangbu, a town about three hours southeast of Guiyang, the provincial capital. Wang had no idea at the time that what he saw on that rock’s face would change his town forever.

“I didn’t really think too much about it,” said Wang, who now works as the emergency administrator for what has become a popular site for those eager to observe what may be the earliest claim of history ever made by the Chinese Communist Party.

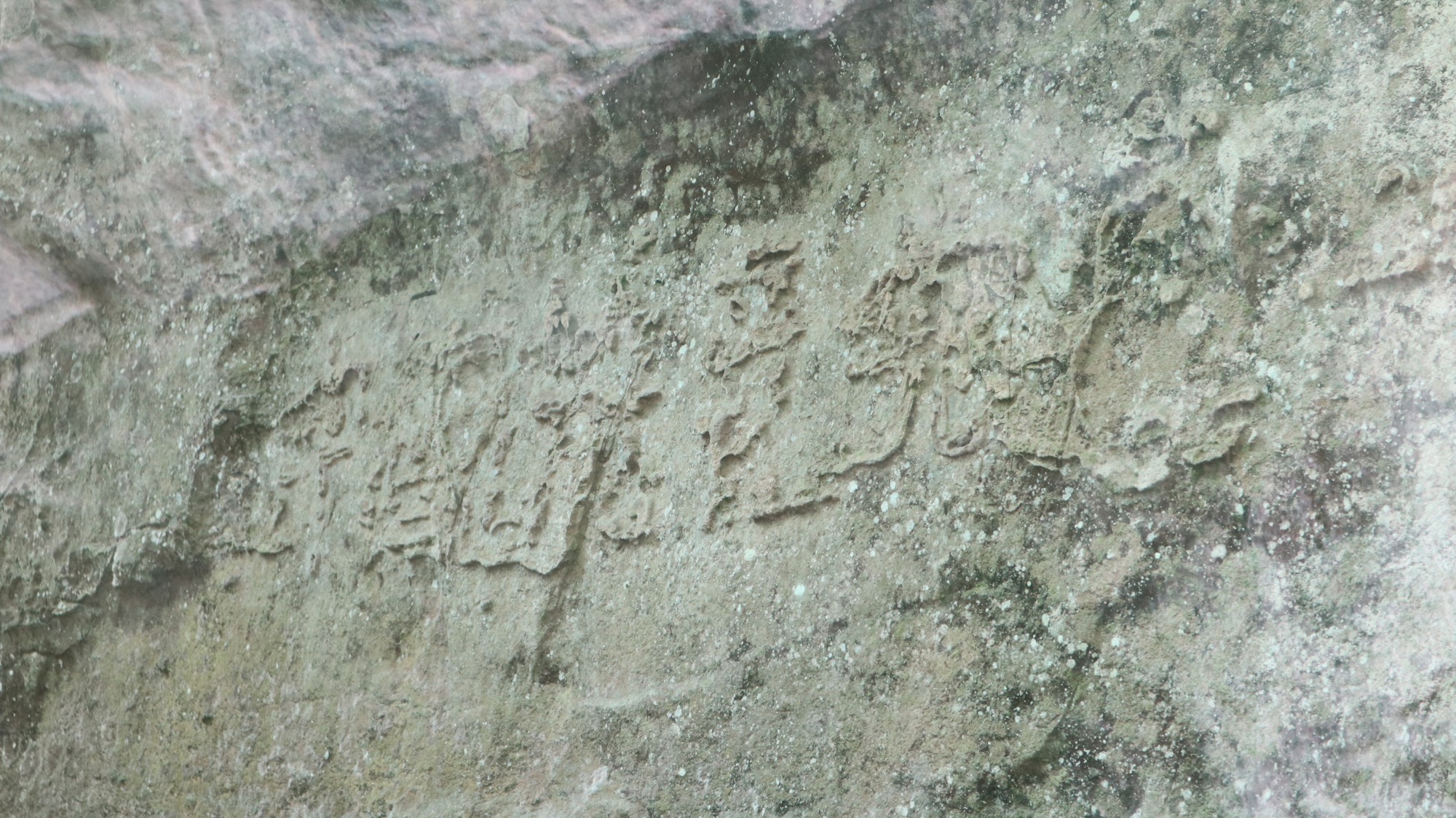

The stone — actually a large boulder — fell from a cliff at some point in the past — some say this happened 500 years ago; others claim it occurred in 2001 — and split into two. Within the gap, there are etchings of simplified and traditional Chinese characters. In one reading, popularized and accepted within the country, the characters read: “Communist Party of China” (中國共產党 zhōngguó gòngchǎndǎng).

Shortly after his discovery, Wang brought a visiting minister from the regional United Front Work Department to the riverbank where the stone is located. “After the minister came and saw it,” Wang recalled, “he said: ‘It needs to be protected.’”

In 2003, a team of researchers from the prestigious Chinese Academy of Sciences and the China University of Geosciences visited the stone and determined it had originated during the Permian era, making it about 270 million years old. The stone, the researchers said, had naturally cracked to reveal the characters, whose formation they ascribed to geological factors; they found no evidence that humans had drawn the characters on the stone. The legend of the “hidden character stone” (藏字石 cáng zì shí) — also known to locals as 救星石 (jiùxīng shí), or the “savior stone” — was thus born. The boulder now rests behind a thick glass display case.

But this isn’t the entire story.

If you look closely, you might see a sixth character, one that takes this tale a completely different direction: 亡 (wáng), meaning “perish,” often used to indicate the death of a state.

中國共產党亡 — The Communist Party of China [will] perish.

I first encountered the stone while searching online for nearby day trips during a visit this summer to Guiyang, where I once lived for two years. I immediately wondered whether this stone in the cloud-shrouded karst mountains of Guizhou, just kilometers away from the triumph of modern science that is the world’s largest telescope, wasn’t hiding the perfect allegory for the Party’s emergent campaign to bend history to its favor.

Modern China has complemented its economic explosion — and its growth into a major geopolitical player — with an interpretation of history that strategically secures its claims on long-disputed territories such as Tibet, Xinjiang, and the waters within the “nine-dash line” of the South China Sea. Although its favored historical narratives regularly incur the wrath of historians, commentators, and international tribunals, they reign supreme within China. As the recent saga with Daryl Morey and the NBA shows, issues of national sovereignty are a sensitive and utterly nonnegotiable subject for the Chinese.

I decided to pay a visit to Zhangbu to gauge how the community treated the myth of the stone. Lying deep within one of China’s less-visited provinces, the stone has almost entirely eluded international attention. Within China, it’s been the subject of a handful of curious reports in state-run media outlets, such as a 2005 People’s Daily news article and a report on China’s CCTV news station. These accounts, of course, strictly adhere to the five-character reading.

Outside of China, my search for English-language media coverage of the stone began and ended with the Falun Gong-backed anti-CCP publication Epoch Times, which reported in 2006 on “a 270-million-year-old “hidden words stone’” with “six clearly discernible Chinese characters; the characters clearly spell ‘The Chinese Communist Party perishes.’” China’s Mystery Files, a TV series on Hong Kong’s Asia Television, also explored the mystery of the stone, nothing that a visiting researcher once explained that the apparent sixth character could represent a date. (The show’s host was entirely unimpressed by this interpretation.)

Keith Fitzpatrick-Matthews, an archaeology officer for North Hertfordshire’s District Council Museum Service in the United Kingdom, wrote on his blog that the rock showed clear evidence of human tampering. “The rock face around the six characters is smoother than elsewhere within the cleft,” he writes. “In other words, it looks to have been cut back, leaving the characters standing proud from the rock.”

Dickson Cunningham, a professor of geology at Eastern Connecticut State University who has done fieldwork in China’s far west but has not visited Zhangye’s miracle stone, was more blunt: “I strongly suspect that it is a hoax,” he told me in an email. “The rock is a Permian limestone but the exposed fracture surface is near surface and very geologically young…and the characters are man-made onto that surface.”

Cunningham added that close-ups of the characters and their edges — which visitors, hindered by the thick shield of glass, are unable to see — and the report from the Chinese geological study “should be made available for peer-reviewed scrutiny in an international forum.” Barring that, he offered his own theory for the origin of the characters: “I suspect it was an anonymous protest expressed as imaginative graffiti.”

Just don’t tell any of this to the locals.

Many Chinese legends have been born from within the gaps of splitting stones.

Sun Wukong, the “Monkey King” of the 16th-century classical Chinese novel Journey to the West, was born when a rock atop the Mountain of Flowers and Fruit burst open to yield a stone egg, which then produced a stone monkey. Several mythological accounts of Yu the Great, of China’s ancient Xia Dynasty, say that the legendary ruler was born from a stone; a similar myth describes the birth of his son who, Chinese literature professor Anne Birrell wrote, was to be “brought forth from his mother’s stone womb, and the miraculous splitting of the stone mother to reveal the child god.”

The splitting of the “hidden character stone” likewise revealed a miracle to the people of Zhangbu. Villagers, said Wang Guofu, “believe that the characters say ‘Communist Party of China.’” The site receives up to one thousand visitors per day, according to a worker at the scenic area.

“Locals used to visit the stone, burn incense, and pray to it because they think the CCP is their savior,” Wang recalled. “They were banned from doing that after a while, because the Communist Party is atheist.”

Before Wang showed the site to the visiting minister, his community, like much of Guizhou in the early 2000s, was poor, isolated, and largely disconnected from the country’s economic boom. Many lifelong residents had never traveled as far as Guiyang, let alone to China’s glistening east coast. Zhangbu was accessible only by a dirt track; the journey, especially after one of the region’s frequent rainfalls, could be treacherous.

That all changed, Wang said, because of the stone.

“The scenic area was only founded after I came across the stone,” he said, describing how its presence revitalized the village. “People’s lives have changed for the better. Tiled and wooden houses are now made of concrete. Roads have been paved.”

Taxis and buses now ply a freshly paved road from the local bus station to the rural scenic area, where a well-kept path ushers tourists to the stone. Wang said he is thrilled by the government’s remaking of Zhangbu to accommodate tourists visiting the Party’s 270-million-year-old geological miracle. “I am proud of the progress we’ve had,” he said. “I’m happy to see that the discovery of the stone brought development to the area.”

The transformation of the village must have seemed like a miracle to the villagers, I thought. How hard, then, could it be to suspend disbelief about the mythical origin of the stone’s etching? After all, that belief is the bedrock of the town’s prosperity, including its shops and restaurants, buildings equipped to withstand earthquakes and mudslides, attention in the form of Hu Jintao’s “Go West” campaign, and funding to develop infrastructure. As expressways and high-speed rail lines have linked the province’s urban centers, and onward with its southwestern neighbors, the stone has ultimately helped ensure that Zhangbu would not be neglected.

“It’s real!” exclaimed a local street cop patrolling the area surrounding the stone. But it’s clear that he’s using the word “real” in a very different sense. When asked whether the words were inscribed by humans, he demurred. “I don’t know, because it’s too far back,” he said. “It’s been verified that it’s real.”

The legend of Zhangbu’s savior stone is relatively harmless. Visitors to the stone can enjoy walks through the scenic area’s array of rock formations, barbecue along the riverbank, and camp during summer nights.But the story of this stone extends beyond the stone itself.

The broader treatment of history by China’s ruling party often has far more severe ramifications than misrepresenting the origin of some etched characters.

For example, China roots its rule over the northwestern province of Xinjiang, which translates to “new territory,” in dubious claims that the land was once part of a Han Dynasty protectorate established in 60 B.C. and is thus historically Chinese land. While there were Han military outposts in parts of southern Xinjiang, it was later uninhabited and then populated by Uyghurs and other groups before an 18th-century Qing Dynasty conquest, which China has never recognized.

This is “historicism rather than history,” said James Millward, a historian of China and Central Asia and professor at Georgetown University. The party is using an interpretation of history to make a point in the present. Here, “historicism” is used to assert historical reign over a territory that currently sees widespread human rights violations against a large Muslim minority.

“The CCP party-state [is] very keen on making these arguments to say that this establishes Chinese priority,” said Millward, who is quick to note that these arguments ultimately serve a narrow purpose. “What they’re responding to is nervousness about legitimacy of their rule in Xinjiang today.”

Internationally, state media such as the tabloid Global Times is roundly mocked for claiming, for instance, that Uyghurs are not descendants of Turks. But domestically, deviation from the Party’s version of history — whether in Xinjiang or elsewhere — can have dire consequences. To followers of the Party, historical arguments, whether claims of a Han protectorate in Xinjiang or of a Permian-era savior stone in Guizhou, are closer to religion.

“They’re encouraging religious-style belief, faith, and worship of the Party,” Millward said. “This new 中华民族 (zhōnghuá mínzú — Chinese nation) has loyalty to the Party as central to this belief system.”

“The Chinese Communist Party,” he said, “is not secular when it comes to the Chinese Communist Party.”

China’s “nine-dash line” in the South China Sea, used to claim islands and waters stretching near Southeast Asian coastlines and claimed in part by six other nations, is rooted in a similarly selective interpretation of history that experts say does not align with reality.

Chinese leaders took an interest in claiming islands in the South China Sea in the early 1900s and immediately began to hone their creativity in the process, according to Bill Hayton, an associate fellow with the Chatham House Asia-Pacific Programme. “You had a process of looking at old documents. ‘You mentioned an island!’ That’s proof,” he said. “But there was never a critical look of whether this island — does it map onto an island you have now?”

Hayton described a process of scrambling to search for anything that resembled evidence of Chinese ownership of a piece of land in the distant waters. “Every piece of information, every document was held up to be proof,” he said. “There wasn’t much logic to it.”

He notes that the phrase “historic rights,” which has become a key facet of China’s firm yet vague basis for its claims in the South China Sea, first gained prominence not within Zhongnanhai but in Taiwan in the 1990s, when the New Party, a nationalist political offshoot of the then-ruling Kuomintang, pushed for the nation to lay claim to the waters as it emerged from decades of martial law. While the Kuomintang-led Taiwan would soon deemphasize its South China Sea claims (though it has not dropped them), China took note of the New Party’s blueprint and reinterpreted it to underpin a campaign of expansionism.

Although China’s claims in Xinjiang and the South China Sea are frequently challenged, some worry that China is getting away with it far too easily. “Few citizens in democracies have taken the time to read long historical articles about Xinjiang and the South China Sea, much less monographs,” most of which are already in paywalled journals or university libraries, said Anders Corr, publisher of the Journal of Political Risk. “So CCP social media and other advertising falls on fertile ground.”

Some claims, such as the recent assertion by Chinese scholars that English is a dialect of Mandarin, are too farcical to pass muster. Others have gained more international traction. Within China, however, it all comes back to faith.

“We’re not the original audience,” Millward said. The arguments “don’t have to work internationally as they do domestically.”

“I think most people don’t know what the claim is based upon, other than this sort of belief that it’s ours and always has been,” Hayton said of the South China Sea. “It’s become an article of faith — that the islands do legitimately belong to us.”

Back in Zhangbu, its Permian-aged “article of faith” is mostly a curiosity for eager onlookers, no matter their actual interpretation of its extraordinary creation myth.

The Sunday afternoon I visited was a quiet day at the stone. A recent flood had damaged one of the bridges, a park staffer explained. Much of the scenic area was closed as the paths were being repaired, and most of the park’s weekend visitors were already on their way out. Of those who remained, most were locals.

Somewhat surprisingly, I was filled with breathless anticipation as I approached. Despite my own agnosticism toward the stone, the short, sign-guided walk to the site fueled the curiosity I had once fed with Wikipedia binges and deep dives into the Chinese blogosphere. Much like the feeling of nearing each crest of a towering mountain, wondering if the next ledge hid the one view that would drop jaws to the ground and instantly justify the agony it took to get there, each small bend on the path carried the possibility that this could be it.

Finally, I arrived. And my first impression was how underwhelming it all seemed.

I had expected it to be larger. More domineering. I wanted the characters to pulse urgently, their message unmistakable. But the letters looked meek behind the thick glass, barely legible (some would say not at all), not exactly booming with might or certitude. Tamed. I wondered which pair of hands — be it human or god — had found itself wedged in that gap, crafting a message of protest, of pride, of desperation, perhaps during times of conflict and fear that defined the first decades of Chinese Communist Party rule. I wonder, now, what message the stone is actually trying to communicate to its growing legions of witnesses. After all, regardless of its origin story, it is quite the remarkable modern story — it is accessible by a well-trodden path, ushering thousands to its bucolic home in the mountains of Guizhou, which has found prosperity thanks to five characters of what just might be protest graffiti.

Maybe it’s just happy to have visitors.

Steps away from the stone, on the bank of the river, a group of departing campers from Guiyang concurred amongst themselves that the stone naturally bears the name of the Chinese Communist Party.

“If it’s artificial,” one man insisted, “there would be marks.”

A woman in the group nodded and sighed heavily. “The wonders of nature!”

Wang, for his part, still marvels at how his discovery of the stone has transformed his village. He finds it incredible that the characters on the stone align with the name of the country’s ruling party. He stopped short, however, of labeling it an important chapter in Chinese history.

“It’s a stone,” he said. “It’s nature. It is what it is.”