SARS and what I learned about keeping a business running during a coronavirus epidemic

How to stay sane as an entrepreneur in a pandemic.

In the summer of 2002, I launched a startup company in Beijing with some friends. Our first employee was a designer from Shenzhen. In the fall of that year, her friends and family started talking about a mysterious lung disease that was infecting people in the nearby city of Guangzhou. Media reporting was stifled, but rumors began to fly around by text message (no social media or WeChat back then).

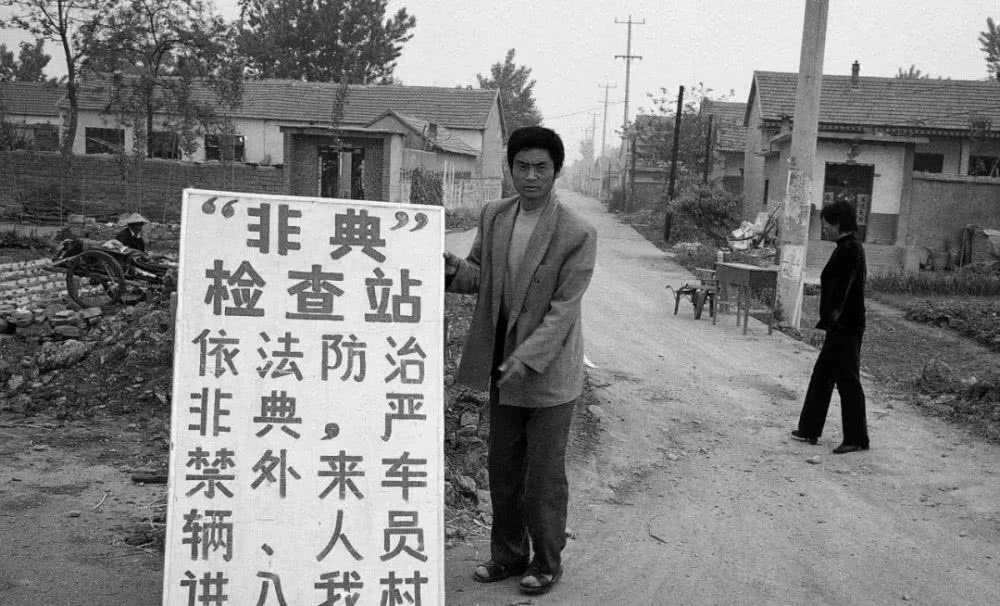

By April 2003, nearly everyone in major Chinese cities was wearing face masks, transport links were suspended, public events were canceled, and many companies drastically reduced or even shut down operations. Some villages, towns, and even apartment complexes erected roadblocks to keep all outsiders away. China was in a similar state to what it is right now.

This is what I learned about keeping a business running — and profitable — when there’s an epidemic raging around you.

Don’t panic, but prepare for the worst

Even if the disease does not turn out to be very dangerous, some government responses to the crisis will be draconian, and the disruption to commerce and travel is already very real.

Your company may be forced to suspend operations or allow only remote working. Most companies in Chinese cities will reduce or postpone nonessential travel and face-to-face meetings. The Spring Festival public holiday has already been extended by three days in Beijing, Shanghai, and other cities.

Your supply chains are already being disrupted: Factories and transport links are shutting down. The government’s priority is to end the crisis looking good, not to restore your logistics network or provide for your health or comfort (see the latest from our science columnist, Yangyang Cheng, for more on this).

“Coronavirus likely will constitute a force majeure event for your Chinese counter-parties and this will mean they can breach their contracts with you without much if any legal repercussion,” says Dan Harris of China Law Blog.

Keep plenty of food and prescription medicines at home and on your person if you travel in case your city, or your apartment block, suddenly decides on a quarantine.

See also “How to avoid the coronavirus? Wash your hands” in the New York Times by Elisabeth Rosenthal, a journalist and physician who covered the SARS outbreak as a reporter in China. Her other key advice is that you and your children should stay home from work and school if any of you are at all sick. She also says that avoiding crowds and enclosed spaces is sensible.

If you’re a foreign national in China, the South China Morning Post has published a list of contacts at embassies and governments. (So far, it includes only Australia, Britain, Canada, France, Germany, and the U.S.A.)

The World Health Organization’s 2019-nCoV web page is here. China’s National Health Commission page that gives daily updates on infection counts and more is here (in Chinese).

Business opportunities

Whatever you do, try to stay positive. Your employees, clients, customers, and everyone around you have frazzled nerves.

If you treat clients and customers well during this crisis, they will be loyal when normality returns. In 2003, our startup company won clients over from our more established competitors because their senior managers all fled Beijing in terror, while we sent over gifts of flowers and face masks.

SARS changed Chinese consumer behavior: Some of the social effects of 2019-nCoV may persist.

- The use of face masks and antiseptic gels across the country remained more common than previously.

- The outbreak convinced many Beijingers to shun public transport and buy a car.

- Beijingers shunned malls and began exploring outdoor attractions in the city. By the end of 2003, the previously quiet central lake area of Shichahai had become a tourist nightmare, but a very profitable one for anyone running a bar or restaurant there.

Winners and losers

There’s no question that 2019-nCoV is going to affect China’s economy — we just don’t know how seriously. The 2003 SARS epidemic cost the world economy around $40 billion, according to some researchers; Asian countries lost $12 billion to 18 billion, according to other estimates.

“The current coronavirus outbreak could cost more than 40 billion yuan ($5.77 billion), which would shave about 1 percentage point off China’s 2020 growth rate,” according to one economist cited by the Wall Street Journal (paywall), who based his numbers on the impact of SARS.

Some observers are sanguine: MarketWatch says that if the SARS epidemic “may serve as a guide, the overall impact of the virus outbreak may be modest and short-lived on the global economy.” A researcher at the think tank MacroPolo says that “the impact on the Chinese public’s consumption patterns and other economic activities should be temporary and modest” if current official estimates of the pace of the spread of the virus are accurate.

Whatever the macro effects, specific industries will suffer, while some benefit:

Airlines, hotels, and travel companies are going to feel pain in their bottom lines and their share prices. The pain could be excruciating: Reuters says the virus threatens disaster for tourist hotspots in Asia, while Caixin reports on predictions that the epidemic will shave 0.2 percentage points from Japan’s 2020 GDP.

Retail will also take a hit, but the recovery will be a little faster once the crisis is over — you don’t need to book ahead to go shopping.

Pharma and healthcare companies, manufacturers of antiseptics and face masks, and traditional Chinese medicine brands will enjoy a short-term boom. Policy changes after the crisis is over could be very profitable for companies that offer the right products and services

Preparing for next time

Now is a good time to increase your preparation for future health emergencies. During SARS, my business partners and I decided to get health insurance for our whole team. I was rarely sick as a young man and did not grow up in America, so I had never feared outrageous hospital bills. I might never have thought about health insurance if not for SARS.

A few years later, the same health insurance package paid a $40,000 private hospital bill in China when I succumbed to an awful allergic reaction known as Stevens-Johnson syndrome (don’t click that link before lunch). A few years after that, my wife was added to the same health insurance package. A few years later, it paid a $350,000 medical bill after the complicated birth of our first child.

In other words, this crisis will pass. And while we should not underestimate the seriousness of the disease and its socioeconomic consequences, planning for the next time your health might be at risk is one productive thing you can do to stay positive if you are running a business in China.