I was on a Chinese film set when coronavirus hit. Things got weird

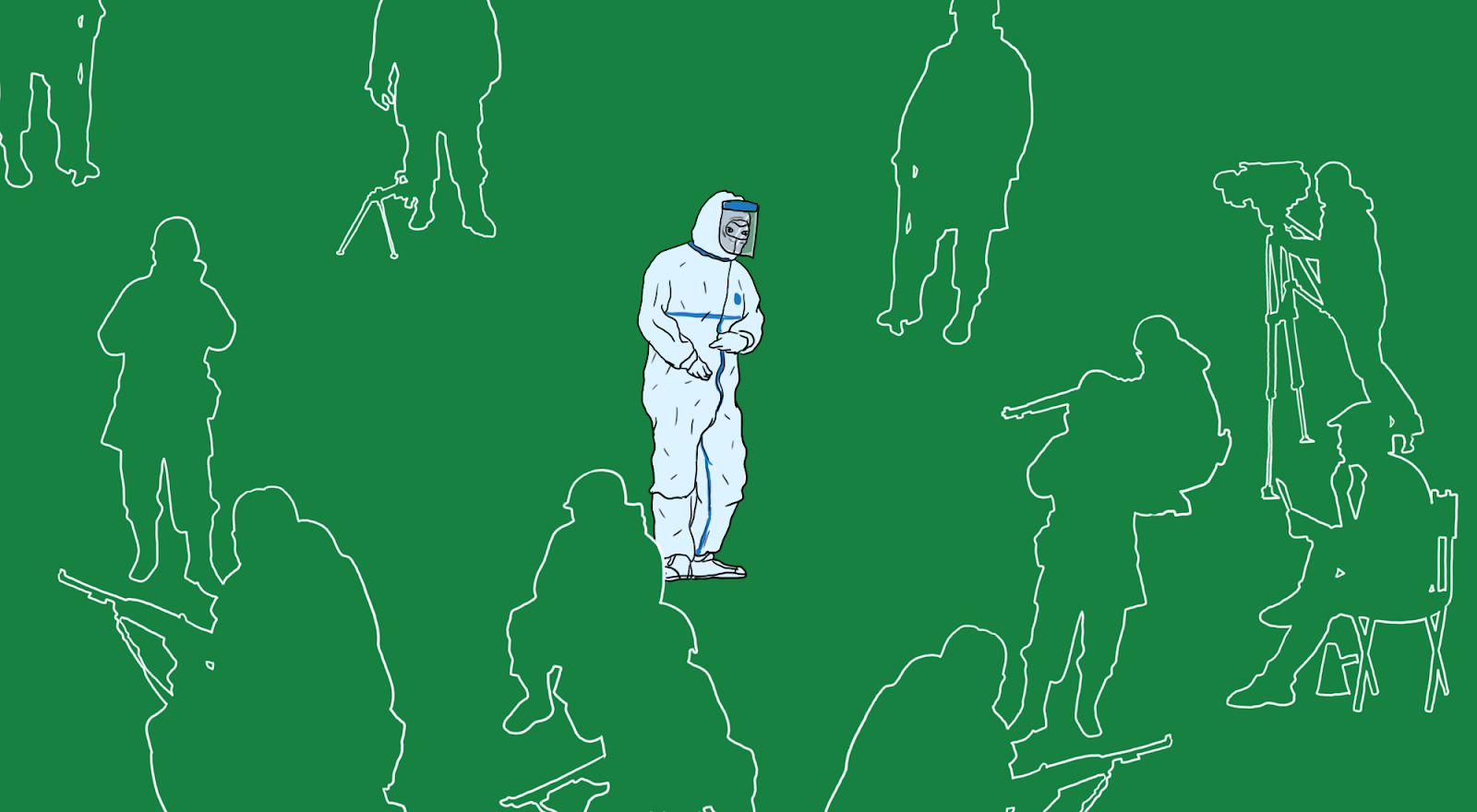

Illustration by Derek Zheng for The China Project

How not to behave during an epidemic.

An unspoken tension rippled throughout our team of around 2,000 as news of the coronavirus began to bubble into our social media feeds in the middle of January. Filming a feature film on location is already a lot of work for everyone involved, but throw in a strange virus, and things can get out of control.

That anxiety only sharpened as we began an indefinite “rest period” starting January 26, three days after Wuhan was locked down. No one knew what was happening.

“Dude, I really need this job,” said Dimitri, on the verge of tears. “Victor, please man, do something, I really need your help.”

Dimitri was a Russian actor playing a bit part as an American soldier, and we were in Kuandian, a small city in Liaoning Province near the North Korean border, shooting a major film about the Korean War.

For me, this was a professional culmination: I had finally made it to the big stage, I thought, as an assistant and translator. For three years, I’d been working in the world of media and entertainment, with some small acting jobs in Los Angeles, Beijing, and Shanghai, but this was my first feature film, and I was excited.

I did not expect my job description to include comforting actors, keeping them from killing one another, and navigating epidemic-induced panic.

Even though Kuandian is 1,200 miles from Wuhan, news about this novel virus shook our small city of 400,000. Local businesses began closing, people stopped taking to the streets, and the few supermarkets that remained open wouldn’t let people in unless they wore a mask.

I was working with hundreds of extras from around the world — the U.S., Russia, Ghana, Rwanda, Romania, and beyond — as well as more than a thousand Chinese employees. None of us expected developments in the coronavirus story to proceed as swiftly as they did. In one moment, we were assured things would be OK; in another, Wuhan was under quarantine.

Considering the amount of money that had already been invested into the film — spent on props, artwork, casting, and training — we all assumed Bona Film Group would keep production going. Only when they halted everything did we get really alarmed.

It didn’t help that the local Kuandian government decreed that any businesses in which people might congregate — karaokes, restaurants, bars, gyms — would have to close until further notice, with violators subject to a fine and suspension. Police patrolled the streets to enforce this edict. Not only were we stuck, but it was apparent that we would have nothing to do.

I spent these days trying to stay busy, working out and reading. Some days, I wandered over to some of the other hotels where actors were staying — and that’s when I saw what kinds of personalities emerge during times of crisis.

“Please stop acting like dumbass ignorant Americans.”

Local police were called on at least one occasion due to fighting. One person went rogue and bought a flight for himself out of the country, but was unable to procure transportation to the airport; he confined himself to his room and had a literal panic attack. (A week later, he trudged out of there with everyone else on a company-arranged flight.) Fireworks were shot out of a hotel window. (More on this later.)

I also observed behavior that made me optimistic for society, such as individuals stepping up to take care of others. Volunteers helped me cater food, because the actors might have starved to death. (I’m just kidding. But also, not kidding.)

There were many rumors, many of them creating rifts between our groups. “So and so has the coronavirus” was something I heard way more often than I needed to. (It was cold in Kuandian; lots of people simply had colds.) Pay was also a huge concern. “Does production plan to pay us?” I heard on more than one occasion. “We haven’t been paid yet!”

“Are we going to be stuck here? Am I going to die in China?” some asked. (I’m sure this will come as a shock to you, but actors can be melodramatic.)

Many of the people around me became addicted to their phone screens, desperate for information about the virus. The more news they consumed, however, the more panicked they became.

I felt bad for some of the foreigners. These were people who probably never imagined, when they left home, that they would be stuck in a foreign land dealing with a mysterious disease outbreak as if they were, um, in a movie. Some actors received nasty messages on their social media platforms; one even got a death threat by someone who was scared that the actor would bring the virus back to the U.S.

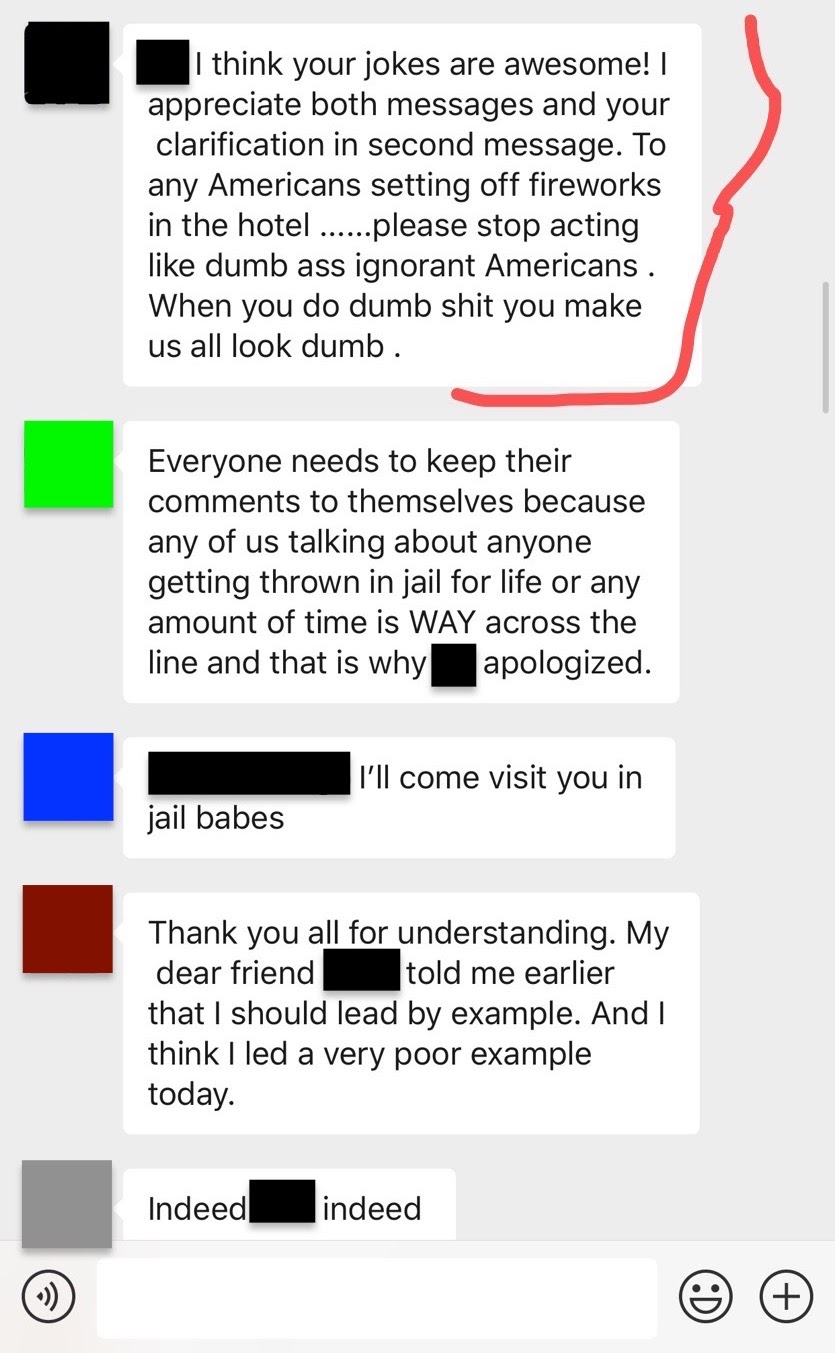

It wasn’t always easy, but alcohol had to be procured. Perhaps alcohol was involved in the room that saw fireworks set off from the window. The details are vague, but the important thing to know is that the hotel explicitly forbade fireworks on its premises, and fireworks should generally never be fired out of a window. That incident led to another one: In our WeChat group, actors got into a heated exchange about Americans making a bad name for themselves abroad.

It started as these things usually do, with some friendly banter:

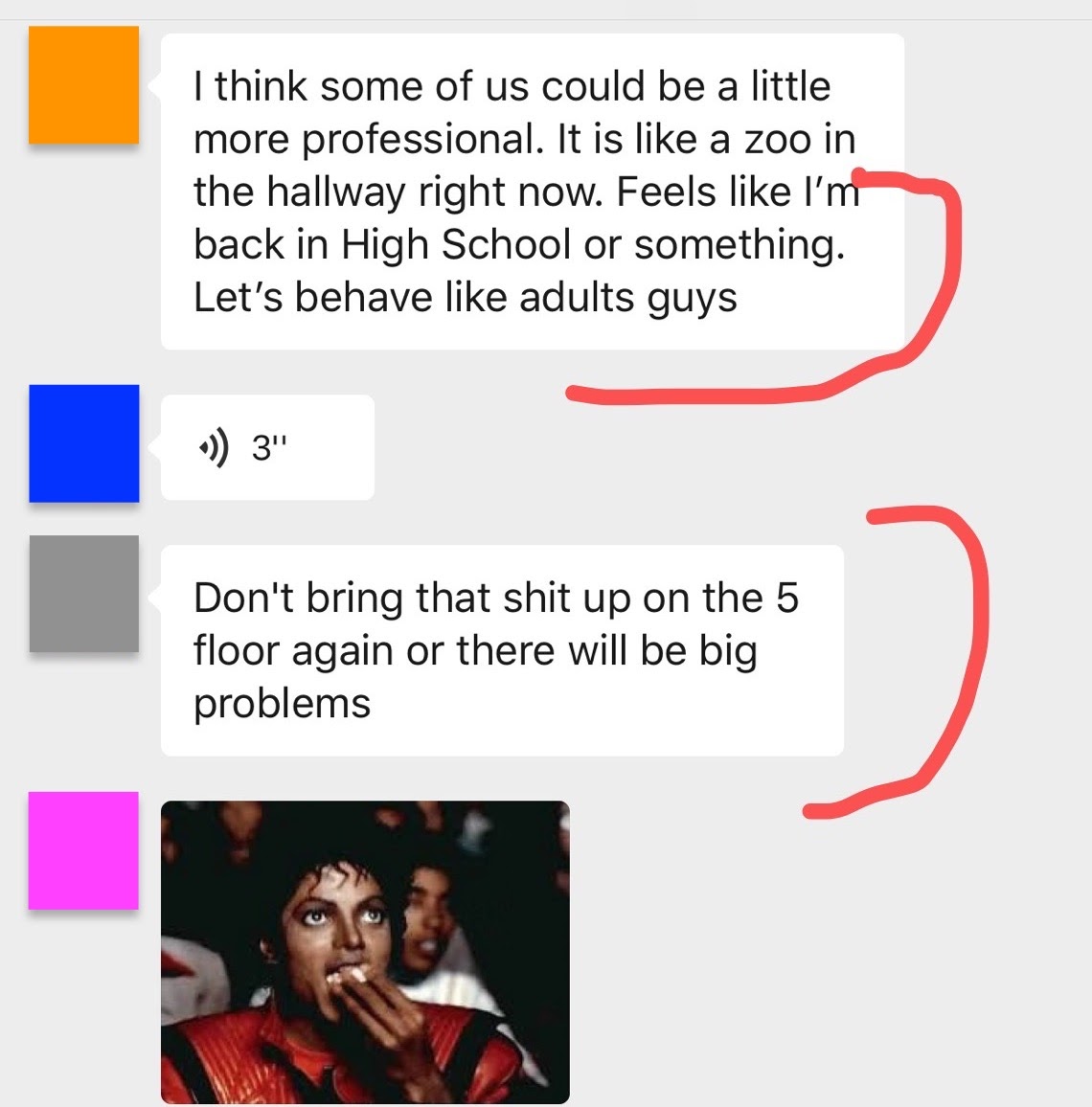

It escalated a little.

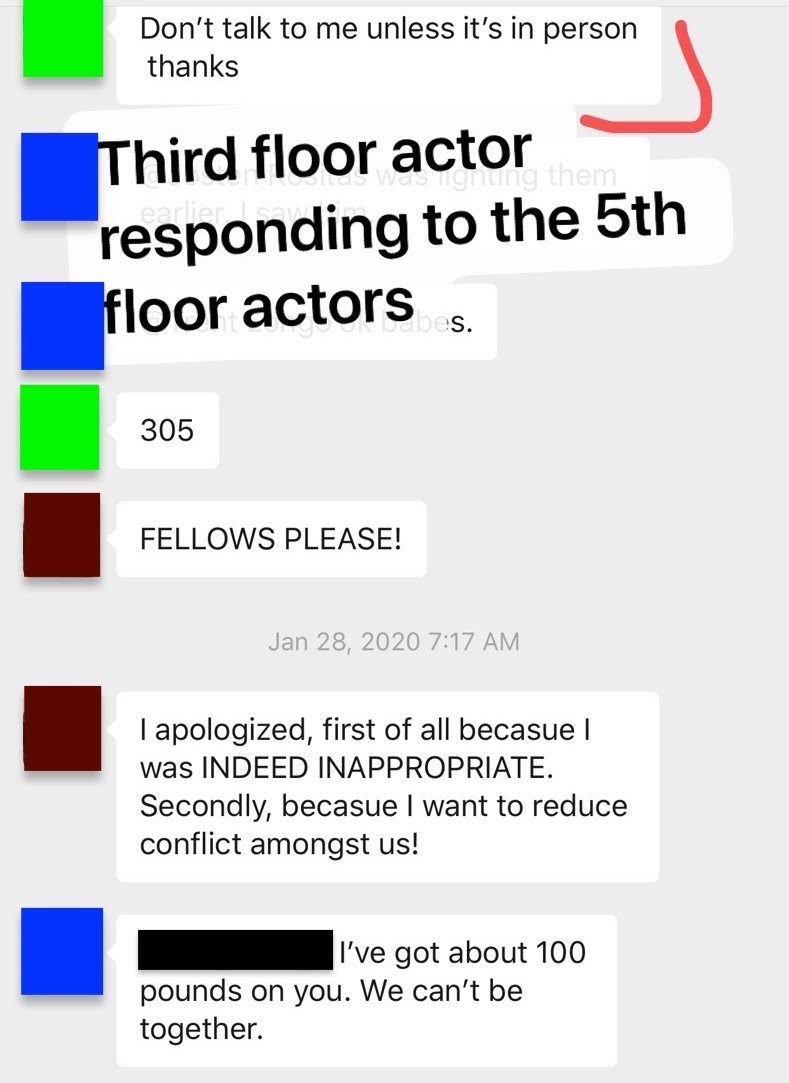

There was clearly a rivalry between the third and fifth floors. “Don’t talk to me unless it’s in person thanks,” said someone from the third floor.

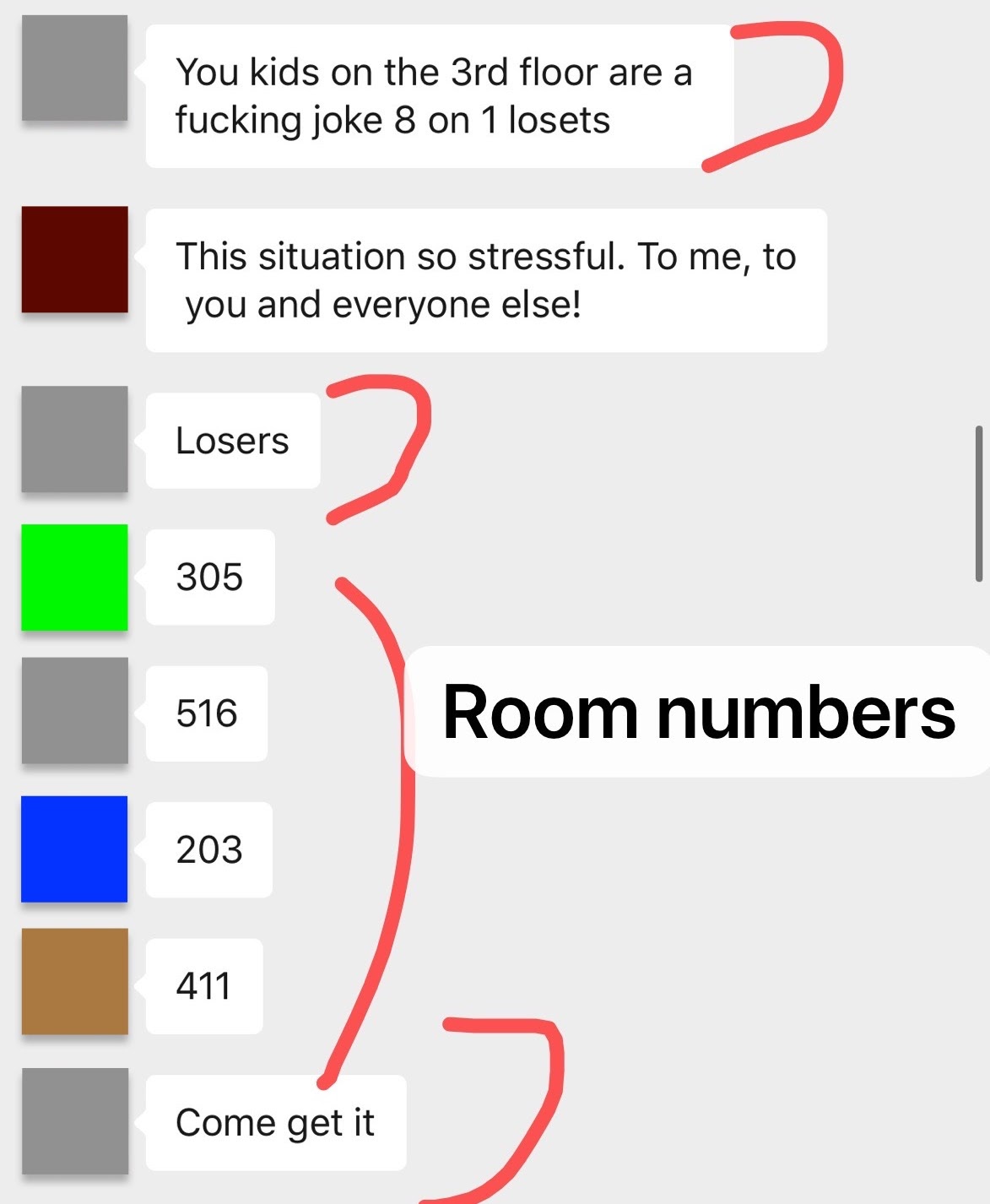

And then it escalated.

“Come get it.”

Sure enough, they did. Two actors from the third floor walked up to the fifth in a fit of drunken rage, banged on a door, and demanded a fight.

A guy on the fifth floor got punched in the face, then put in a chokehold, and passed out. I know all this because I was responsible for the aftermath. I made everyone get out of their rooms and give statements.

Afterwards, I heard there were more disturbances, with actors flashing their private parts at each other. I began to wonder if this was just what actors do in the wild. I hadn’t been in the industry long enough to know for sure.

That particular night ended with all American actors having to surrender any fireworks they may have been hoarding (many people bought them for Chinese New Year). Three actors were fired, on the spot, without pay. Their passports were confiscated by production, with about a dozen Chinese police officers present. The actors in question berated the staff and threatened to sue the production.

Some people were relieved by the “indefinite postponement,” while some were upset to have to abandon three months of paid work. For others, the postponement felt more personal.

Dmitri, for instance, had left his life in Siberia for this project. He was a younger actor without much experience, but like many of us, had dreams of bigger roles, bigger accomplishments. Like me, he got on set in early January. “I feel so happy and lucky to be here with actors from all over the world, from the U.S., from China,” he had told me. “I’m from a small town in Siberia, I don’t really have many chances to do acting work, so I feel really luck to be here.” He had wanted to pursue more gigs in China, potentially make this country his home.

Many of us had invested emotional energy into this project, and it was hard to let go. But we distracted ourselves with more pressing concerns.

We could still get food, though not always with ease. I’ll always be grateful to one Chinese bar/restaurant that stayed open despite being told not to — it prepared box meals for us every day, even preparing specialties such as dumplings, popcorn chicken, chicken curry rice, French fries, grilled cheese sandwiches…and beer, of course.

As production was arranging flights out for everyone, I was personally put in charge of the well being of three American trainers who had been hired as consultants.

One of them left first, so I accompanied him to Shenyang International Airport and said goodbye, figuring that’s the last I would hear from him. He was headed to Albuquerque. It wasn’t until I got back to my hotel that I got a frantic phone call from him.

“Dude, my flight payment did not go through!” he said.

I admitted this was a problem.

“I don’t know what to do…I don’t want to get stuck here!”

“I’ll see what I can do,” I told him. “We will get you out.”

Thanks to our accounting team, we got him a flight out the next day, for a reasonable price of $1,400.

Two days later, it was my turn to leave with the other two trainers. I said farewell to Dmitri, who thanked me for the attention I gave him on set and for listening to him in his time of need. He still didn’t have a flight out, so I mostly did the talking to reassure him.

“I don’t know what I can do, but if you need anything, please call me anytime,” he said. (I learned that he was able to fly out about five days later.)

The two trainers and I took a company van — we had to go to the train station first to drop them off, as they were headed to Beijing. During the ride, we all took turns noticing the driver’s eyes rolling into the back of his head. The car would also lurch from side to side before jerking itself back into its lane. Luckily there were few cars on the road, because our driver was clearly falling asleep at the wheel.

We told him that if he wanted to rest, he could. But he insisted he was fine. I patted his shoulder and yelled at him to keep him awake. I told him our lives were more important than getting to the train station.

He admitted that he did not sleep well the previous night. He had to wake up at 4:30 a.m. in order to pick us up. On top of this, he was overworked. I must say, I understood the feeling. In his car, I also had to slap myself a few times to keep awake.

We gave him an energy drink.

With a sigh of relief, we made it to the train station with 45 minutes to spare. I said goodbye to the two trainers. And now, finally, I could turn my attention to myself.

Our tired driver got me to the airport safely, and when I arrived, I felt a weight lifted off my shoulders, knowing I had done everything I could to keep the people on a major movie set sane during a time of crisis. But just as I was ready to relax, I discovered that production had failed to secure my ticket. They confirmed a booking, but had forgotten to pay.

They bought me another ticket, but the only way out of Shenyang was through Incheon, South Korea, then Istanbul, before finally arriving at Washington, D.C. It would take 50 hours.

I’ll spare you the details of my odyssey. When I finally landed at D.C.’s Dulles Airport, I was bleary-eyed and at my wit’s end. Still, there was one last obstacle: customs.

I must have looked suspicious as I walked up to the counter, disheveled and exhausted as I was. The customs officer asked where I was flying from.

“China,” I grumbled.

His eyes widened and he looked up, as if remembering his training.

“Have you been to Hubei during your trip?”

“No.”

“Did you interact with anyone from that area?”

“Nah.”

“Are you bringing in any animal or agricultural products?”

“Uh, no.”

“Do you have any cold or flu symptoms?

This was the question I feared most, since I suspected I must have looked sick. I certainly wasn’t feeling healthy after two full days in airports and on airplanes.

“Nope,” I said.

The officer paused, looked at his screen, looked at my passport, and then looked at me. I was so tired that I would not have put up any resistance if they told me I had to go into quarantine. I could’ve used the sleep.

I counted to five Mississippi in my head.

“Welcome home,” the officer said, stamping my passport and handing it back.

Oh, and I still haven’t been paid.