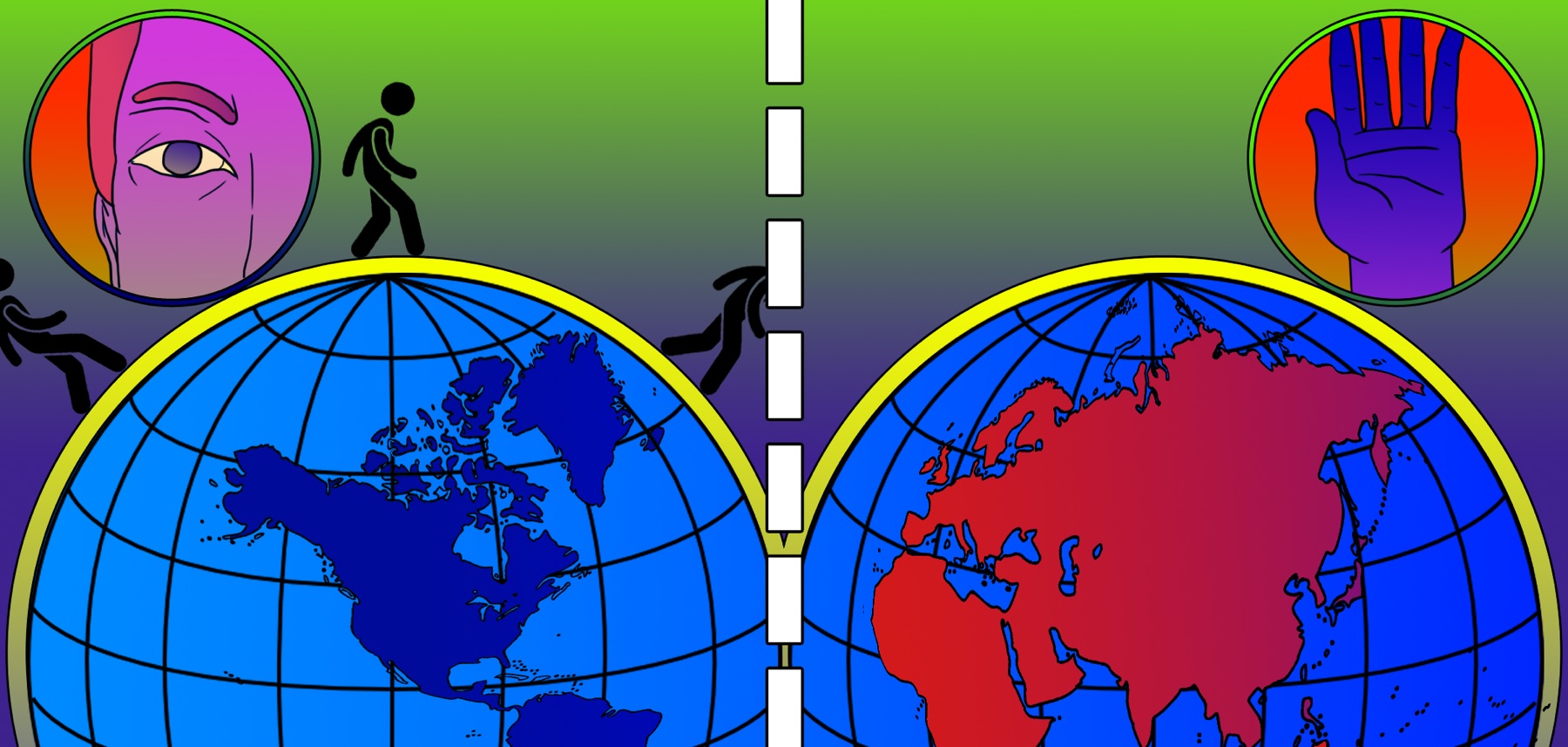

Fault Lines in Humanity

Illustration by Derek Zheng

A state’s ability to protect is simultaneously its permission to do harm. The tyranny of the border is always imposing itself — amid scientific collaborations, in disease outbreaks, and against those who stand at the edge of nationhood.

I crossed a border every day to get sandwiches.

It was the summer of 2010. I had just finished my first year as a Ph.D. student at the University of Chicago. Before class resumed for the fall, I spent a few months at CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research. It is home to the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), the world’s largest particle physics experiment.

With a Geneva zip code, CERN is located on the Swiss-French border, its circular collider traversing both territories. The detector I worked on is on the Swiss side, as is the hostel I stayed at. Due to a university accounting error, I found myself surviving on two Swiss francs a day. Luckily, not too far in the other country was a Carrefour, its shelves of sliced bread and cold meat a literal life saver.

I made the trips on foot. When the sun was hot and the air dry, I would imagine the asphalt beneath me stretching on forever, into the snowy mountains or to the edge of sea. When the familiar buildings emerged from a distance, I knew once again I had arrived, a different country behind me, neither of them home.

CERN was established in 1954. Like other European communities founded in the aftermath of World War II, the organization serves not only a professional purpose — in this case the advancement of science — but also an ideological one, that a common pursuit can help unite historically hostile nations.

“The Organization shall have no concern with work for military requirements and the results of its experimental and theoretical work shall be published or otherwise made generally available,” reads CERN’s convention. Its research shall be “of a pure scientific and fundamental character.”

Over the decades, CERN’s initial list of 12 member states has grown to 23. Hundreds of institutions from dozens of countries on six continents contribute to its experiments. The laboratory has, in many ways, represented science at its cosmopolitan ideal. Nevertheless, like any transnational organization in a divided world, where no passport is created equal, operations at CERN constantly pit its lofty mission against a grinding reality.

While I made daily trips from Switzerland to France and back, oblivious to the border on my way, I was also waiting for the U.S. government to renew my student visa. The process usually took 20 days, but could drag on for an indefinite amount of time. What should I do if my short-term European visa expired before I could return to the U.S.?

“I might have to report myself to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees!” I joked to my American advisor. We both laughed, and I felt embarrassed for appropriating the plight of millions for comic relief. I had stumbled upon the agency’s Geneva headquarters on my first trip to CERN the year prior, days after my college graduation in China. That weekend, I walked alone for hours with no sense of direction, and hitchhiked on a stranger’s empty, unmarked shuttle without a shred of concern. It was a time when my understanding of human suffering was limited to that of the family, when I believed if I made my way out of China, I could make it anywhere.

There were no more solo adventures the second summer. As my passport lingered at the American embassy in Paris, each passing day brought a new terror. I confined myself to the lab, limiting outings to the supermarket and back. If I stayed inside nothing bad could happen. If I stayed inside I would not get lost.

My visa arrived after weeks of anguish. I felt silly for the excessive worrying. On the Blue Line back from O’Hare, I listened to the rumble of the train track, and felt the ground swell. I let the city hug me. Its body of concrete and steel soothed my nerves, consolidating my splintered self. The iconic skyline appeared more majestic than ever. I had left the border behind, and I did not look back.

I stood in front of the United States Capitol, my red coat burning against the pale edifice. I posted the photo on Twitter. Hashtag: What democracy looks like. Timestamp: March 11, 2018.

Earlier that day, the National People’s Congress, China’s rubber-stamp legislature, passed a constitutional amendment that removed presidential term limits. The vote was 2,958 in favor, two against, and three abstentions. The development, however significant, was largely symbolic and a long time coming. For years, Beijing has been tightening its authoritarian grip, and Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 made himself the most powerful Chinese leader since Mao.

I felt the urge to say something, to mark the occasion for my own record. The choice of the image and use of a public forum were self-aggrandizing. I watched my birth country’s descent into darkness and felt helpless, so I turned to a cliche: The Statue of Liberty. The star-spangled banner. The shining city on a hill. The beacon of freedom.

The photo was taken a few days prior. In the years since I finished graduate school and continued working as a particle physicist in the U.S., I made regular trips to the Capitol with my colleagues, meeting with members of Congress and their staff to advocate for federal support in basic research.

The visits were exhilarating in the beginning, the very proximity to power a potent boost to the ego. We looked for famous faces in the hallway, and took photos next to plaques engraved with the names of elected officials. We sat down in the representatives’ offices and opened our packets, every word in our pitch selected with care: Particle physics is fundamental science, but the technologies developed in the course of our inquiries have broad applications. The World Wide Web was invented at CERN. CERN is located in Europe, but the U.S. is the largest single country contributor to its experiments. There are U.S.-based particle physics projects as well. This is the amount of federal grants for our research that went into your district. This is how much one national lab in Illinois spent on equipment and service from businesses in your state…

Wholehearted participation requires a degree of surrender, the passive acceptance of rules, the relinquishment of doubt. I do not know anyone who chooses particle physics as a career motivated by the prospects of financial gain. I want to tell the Senators and congresspeople that the United States should invest in basic research not for narrow self-interest but for humanity, that as human beings we are drawn to fundamental questions about our existence, and if we as a species could get closer to that shared truth, maybe we would also be less likely to kill one another.

My colleagues concur with my sentiments, but they tell me to be pragmatic, to speak in terms elected officials care about: Money. Jobs. American power.

The discourse is no longer about individual misconduct, nor is it centered on the ethical development and responsible use of technology. Scientists are portrayed as strategic assets in geopolitical rivalry.

The U.S. government has been placing extra scrutiny on academic institutions and personnel with connections to China. The practice dates back decades, but has intensified in recent years, largely in response to the Middle Kingdom’s economic rise and the unsavory tactics it deploys to acquire foreign technology and foreign-trained talent. Several U.S.-based scientists have been indicted by the Justice Department, with charges ranging from intellectual property theft to failure to disclose foreign income. Funding agencies issued new guidelines on international collaboration, making participation in foreign talent recruitment programs a disqualifier for federal grants. Scientists of Chinese origin face additional hurdles to study or work in the U.S., including prolonged visa processing and restrictions on facility access.

The debate on academic freedom versus national security is not new. Concerned about Soviet acquisition of advanced technology, the Reagan administration convened a study on the need for controls on scientific information. The conclusion, issued in 1985 as NSDD-189 (National Security Decision Directive), states, “It is the policy of this administration that, to the maximum extent possible, the products of fundamental research remain unrestricted.” The directive, reaffirmed in 2001 and 2010 under both Republican and Democratic leaderships, is being reevaluated by policymakers in D.C.

The goal, they say, is to protect national interest: American taxpayers fund American science for American gain.

I don’t really know the meaning of “American science.” How does a state build walls around an idea and claim it as one’s own? As a Chinese person who works for an American university on a European experiment overseen by an international collaboration, to whose government does my science belong? For a commercial application that was developed in the states, is the technology still American after the company is sold to a foreign investor? When the federal government steps in to block such transactions with increasing frequency, what are the implications for the free market, a concept America uses so fervently to define itself?

Dishonest behavior should be condemned. Criminal acts should be prosecuted to the full extent of the law. Intellectual property needs protection. Academic integrity must be upheld. But the discourse is no longer about individual misconduct, nor is it centered on the ethical development and responsible use of technology. Scientists are portrayed as strategic assets in geopolitical rivalry. Tons of ink are spilled on whether America is still in the lead and what it must do to maintain the top position, with few questioning why this country deserves the most power and if it’s good to have it. A state abuses technology to advance state interests, regardless of its governing system. But as long as us means “Democracy,” which is good, and them means “Communism,” which is evil, the United States can avoid serious examination of its injustices, and justify expanding its arsenal under the banner of defending freedom.

In the psychology of empire, more science is better science; bigger guns are good, as long as they are pointed in the other direction. A border is no guarantee of safety, but by picking a side, it provides a cause worthy of living.

My mother tells me she’s running low on vegetables. In an effort to stretch what’s left in the fridge, she realized that orange peels are edible.

“I drizzled them in oil and stir-fried them. It’s pretty good!” There’s a giddiness in her words. She goes on to describe the nutrient value of her culinary innovation, and how vitamins are important for a strong immune system.

My mother lives in China. Due to the coronavirus outbreak, she has not left her apartment for weeks. Her city is hundreds of miles from the epicenter of Wuhan, and there is no official quarantine order. I want to tell her that it is most likely safe to go outside, but I do not want to sound cavalier from the safety of an ocean away. Instead, I convince myself that there is no harm in consuming orange peels, and people of my mother’s generation have endured greater scarcity: She can take care of herself! She’s resourceful, and in good spirits.

With the first cases surfacing in December, the acute respiratory illness known as COVID-19 has infected some 80,000 people and claimed thousands of lives. Most of the casualties are in Wuhan. In an epidemic, fear spreads faster than the disease. Since late January, restrictions on movement have been placed in virtually all of China. Flights are cancelled. Roads are blocked. Buses have stopped. Factories remain closed. Schools have moved lectures online. Hospitals suspend treatment for non-coronavirus patients. Permits are required for people to leave their residential compound. Fire trucks press through empty streets, dousing the air with disinfectants. The wearing of face masks became mandatory: Violators can be charged with public endangerment.

Behind layers of gauze, humanity is stripped to its conflicting instincts. The killer is among us. The killer is all of us. Everyone wants to escape. Everyone wants to be the last person standing. From the seclusion of their homes, people donate generously to the aid of Wuhan. For a healthy person rumored to be from the afflicted region, they are avoided like the plague.

Dozens of countries have evacuated their citizens out of Wuhan, a city in lockdown since January 23. Does a foreign passport make one more deserving to live? It’s a question too cruel to ponder. In the eyes of a state, people are also a bargaining chip. As the Chinese government tries to uphold its image of handling the crisis, developing countries weigh the commitment to their citizens against their relationship with the world’s second largest economy. The Kenyan embassy repeatedly denied the request for assistance from its students in Wuhan. After the Pakistani ambassador stated that his country would not evacuate, “in solidarity” with China, Beijing praised the western neighbor as “an iron ally.”

My mother sends me blog posts comparing the evacuation efforts of several European countries: the number of planes, the quarantine accommodations, the meals provided. “Look,” she says, “only a strong nation can protect its people.”

The U.S. government issued a new directive, prohibiting all foreign nationals who have been to China over the past 14 days from entry. Exceptions are made for immediate family members of U.S. citizens and permanent residents. Several other countries implemented similar policies. The virus sees no nationality, but a state is not obligated to anyone outside its own. In response to the outbreak, the sharp edges of sovereignty are laid bare, its ability to protect simultaneously a permission to harm.

From Boston to Berlin, Chinese restaurants report a decrease in the number of customers, while racist remarks toward people of East Asian descent occupy newspaper headlines. The association of foreign bodies with disease is as old as nationalism itself, and latent prejudices are given new license in the name of public health. In an attempt to define the other, people reveal themselves.

My mother finally went outside for groceries. She wore three layers of masks. “I heard that the CDC (Centers for Disease Control) says masks are only needed for sick people,” my mother writes. “Don’t listen to them. Americans are of a different race. Chinese people wear masks.”

On the day the suspension of visitors from China to the U.S. was announced, the Trump administration added six more countries to its travel ban, expanding the list to a total of 13. The “unwelcome” people are from Africa, Asia, South America, and the Middle East. They speak different languages, and worship different gods. The only thing they seem to have in common is that they are not white.

I was chatting with a friend when the news broke, whose family came from one of the banned countries. We tried to offer words of comfort to each other, which only made us sadder. So we turned to cheap humor, cracking jokes about whose homeland has a worse government, and which is hated more by the U.S., where we both live. “What might kill us first, war or the virus?” We shared an awkward laugh.

The border is an imaginary line: It does not need protection.

Among the countries included in the latest round of restrictions, one received particular attention in the media: Nigeria. News reports are quick to point out that Nigerian immigrants and their children are more likely to have college degrees than the overall U.S. population.

It is a curious detail to mention. Is banning Africa’s most populous country a more egregious mistake than a place where the average emigre has spent fewer years in school? The obvious answer is no, though for an administration that has repeatedly tried to justify its racism and xenophobia by claiming it wants “the best and the brightest,” the ban on Nigeria does expose its hypocrisy.

There is no “do it the right way” when the crime is the color of one’s skin. As Iranian-Americans face questioning at the border, and the Supreme Court guts voting rights, recent events serve as a reminder that citizenship is always conditional, that this country founded on slavery and genocide only recognizes the ones who meet its definition of whiteness.

In the 10 years I’ve spent in the U.S., I’m often told by well-meaning Americans that “We want more people like you!” I appreciate the gesture; however, it is patronizing. Who is “we”? The decision to leave my country of birth was not to fulfill another person’s desire. I did not seek external validation.

And what is “people like me”? The only trait that matters in this discussion is my foreignness, but it is never what they refer to. I am wanted because I have something to offer, my degree, my profession, my skills.

For the ones who have never faced the tyranny of the border, and those who made it to the other side and internalized the humiliation as the way of life, the immigrant is a brain, a body, a criminal, invisible until hypervisible, a prize or a menace, but never fully human. The deed to the new home carries a lifelong mortgage, and its occupier must constantly prove their worth, in work and in gratitude. The narrative of immigrant excellence is seductive, even inspiring, but it is an argument constructed on scarcity, not generosity. The country that celebrates the Nobel laureates and Fortune 500 CEOs who came to its shores can use the same logic to turn away anyone who does not meet its narrow definition of success, and to tell the rejected they have no one else to blame but their own inadequacy.

“We need to keep our borders secure!” the politicians say. Then they add a few words on letting people “come in legally” to signal magnanimity. Law and order is a dog whistle. The border is an imaginary line: It does not need protection. Migration is a human right; it is the state that created the criminal. The ones who stand on the edge of nationhood should be the center of the world. Only by protecting them do we preserve our own humanity.

Instead, we look away. We put the most desperate in camps and cages and banish them to an island because we cannot stand to look at ourselves, to confront our greatest vulnerability and deepest fear, that we too may not belong anywhere. We collude with the state for its mercy. We tell ourselves lies in order to live.

Over a hundred meters underground at the Swiss-French border, the effect of the coronavirus outbreak is felt by LHC experiments. There are no known cases in Switzerland to date, and CERN remains open, but some pieces of hardware, intended for detector upgrades, are locked inside Chinese campuses.

“No one thought of adding global pandemic to the risk assessment!” an American colleague joked. All of our meetings are video conferences across several time zones, and the LHC sends its data all over the globe. If only equipment can be converted to strings of ones and zeros.

Particle physics experiments operate on a timescale of decades. At a workshop years ago, a colleague made a passionate remark that kids in elementary school today may be pursuing their Ph.D.’s using the machines we build: How are we fulfilling our responsibility to future generations? I have paraphrased the argument on visits to the Hill, and told representatives that children from their districts will benefit from the projects they fund. The line is received well, though sometimes I wonder whether politicians care about anything beyond the immediate election cycle.

It is often easier to envision a technological breakthrough, or an alternate universe with its laws reversed, than to question the basic mechanisms of human society, the pattern of ordinary life whose stability we rely on to plan for tomorrow, to continue with our activities, to dream. A global pandemic is a specific scenario, but as long as borders exist, they may close or break at any moment for a variety of reasons: war, civil unrest, disasters natural or manmade. A government shuts down the internet. A region becomes uninhabitable due to climate change.

These are not far-fetched hypotheses. They are realities on this planet at this moment. I do not know if the possibilities did not cross my colleagues’ minds because of privilege: Particle physics, for all the laudable strides it has made toward diversity and inclusion, remains a first-world profession with first-world problems. I’m afraid there are people I work with who think the coronavirus is a third-world disease, and that I, as a Chinese person, should somehow apologize on behalf of my country for how it has inconvenienced their very important science.

Maybe I’m being too harsh, that observing tragedies has made me cynical. I tell myself the least I could do when a calamity unfolds is to bear witness, as a writer and as a person. Part of my motivation is selfish: I hope the awful glow of loss can help illuminate the human condition, but there is no truth more profound than how quickly everything can unravel, and how easy it is to die.

Many years ago when I was still new to the U.S., I was at a friend’s graduation ceremony when someone congratulated her: “No matter what happens, no one can take your Ph.D. away.” I remember the pang of envy I felt, as I imagined moving through the world with that prestigious title, the doors it could open, the sense of security it must provide. When I finally received the same certificate with my name, it was only a sheet of paper: an important sheet of paper by some banal standards, but I woke up the next day the same person as the night before.

I have three important sheets of paper as the world sees it: my Chinese passport, my U.S. visa, and my Ph.D. diploma. It is somewhat ironic, that with the tenuous relationships I have with both my birth country and my adopted home, as well as the directions both governments are headed, my diploma is the paper I am least likely to lose. I do not want to give a romanticized notion of a degreed education, as that is in itself conditioned on privilege. However it fails egalitarian principles, the academy has, at its very best, challenged and transcended the state. I am reminded of the fact that the oldest university in China has outlived two Qing emperors, several Nationalist leaders, and numerous Communist party secretaries. Books are read long after the death of kings who ordered their destruction. My writing gets me into trouble; it is also through writing that I find my truest existence.

A map is only one story. A person cannot be contained by lines on paper. My humanity is not defined by a stamp from the authorities. The unruly part of me that the state finds most threatening is also what the state cannot take away. I let it expand, and feel the awakening of an ancient power.

Yangyang Cheng and the Science and China Column will return on the final Wednesday of every month. Last month: