COVID-19 fuels domestic violence in China

As China fought to slow the spread of COVID-19, vast numbers of Chinese people were advised to practice social distancing, and self-isolation. While home was widely considered the safest place in the time of the coronavirus, the outbreak proved to be an especially dangerous time for those living with an abusive partner or family member.

“Before today, being a victim of domestic violence was the furthest thing from my mind,” a 42-year-old woman surnamed Li wrote on WeChat on March 9. “But today is a nightmare to me. Fear and the feeling of hopelessness are suffocating. I’m completely in a mental breakdown!”

Two hours after she wrote the message, Li leaped to her death from the 11th floor of her apartment building in Shanxi Province. On March 12, the local police announced (in Chinese) her suicide to the public, and that her husband had physcially abused her while in quarantine together.

As China fought to slow the spread of COVID-19, vast numbers of Chinese people were advised to practice social distancing, and self-isolation. While home was widely considered the safest place in the time of the coronavirus, the outbreak proved to be an especially dangerous time for those living with an abusive partner or family member.

Under the Blue Sky (蓝天下 lántiānxià), an anti-domestic-violence nonprofit based in Hubei’s Lijian County, received a total of 175 reports of domestic violence in February — tripling from 47 such complaints during the same month in 2019. In an interview (in Chinese) with the Southern Weekly, Wàn Fēi 万飞, the founder of the organization, said that after cities in Hubei were put under lockdown, their hotline experienced a spike in calls from domestic violence victims. “On peak days, more than 10 people called in for help,” Wan said.

Since its establishment in 2014, Under the Blue Sky has developed into a team of 80 professionals from different walks of life, including lawyers, psychiatrists, and law enforcement officers. But according to Wan, the coronavirus pandemic has posed unprecedented challenges for the organization, as victims were stranded inside their homes with no help from the outside world available.

Wan told the newspaper that when the virus started to spread across China last December, he already anticipated that the rates and severity of abuse would surge as the government tried to curb the epidemic through asking individuals to self-isolate. “The outbreak had many people who already had violent partners confined to their homes with abusers. The anxiety and depression caused by the high-pressure situation tends to increase the possibility of domestic violence,” Wan said.

To make things worse, the pandemic also led to travel restrictions and the closure of most businesses, which made it even more difficult for victims to reach out to friends, or to find temporary housing outside of their homes. In a story (in Chinese) shared on Chinese social media, a woman in Guangdong Province, who suffered from life-threatening violence when staying at her ex-husband’s house in January, was told by local officials that she was prohibited from leaving her village even after she explained the situation. In a desperate move, the woman fled her abusive home with her two kids and walked for hours before a family member picked her up.

Theoretically, now, perhaps more than ever before, is the time for anti-domestic-violence groups to extend their services and create awareness of the issue. But Wan was worried that his organization’s philanthropic efforts would be seriously impacted by the tough economic times brought on by the pandemic. “It’s hard to fundraise amid the coronavirus. We are short on staff, but most financial resources are devoted to combating the virus,” Wan said.

On the legal front, despite China’s introduction of landmark anti-domestic-violence legislation in 2017, sexism and the backward view that domestic violence is a private family matter still cloud police responses to survivors calls for help. In February, when a woman in Shenzhen reported her abusive boyfriend to the local police, she was told that “her complaint would ruin the career of her boyfriend.” Unable to attract the attention of police officers, the woman took to social media to share her account (in Chinese) of being abused and an audio recording she made during a domestic violence incident. After the post gained traction, the local police i issued an announcement (in Chinese) on Weibo, saying that they would detain the abuser and apologizing to the woman for the delay in response.

Meanwhile, for survivors seeking protective orders from courts, counseling and legal services have been largely inaccessible as court officers work from home. According to activist Féng Yuán 冯媛, who co-founded a Beijing-based nonprofit focusing on women’s rights, while survivors can lodge complaints of domestic violence online, those unfamiliar with the internet are at a disadvantage. “An increasing number of survivors are aware of their rights and want to hold perpetrators accountable. They are ahead of the time, but relevant institutions are still far behind,” Feng said.

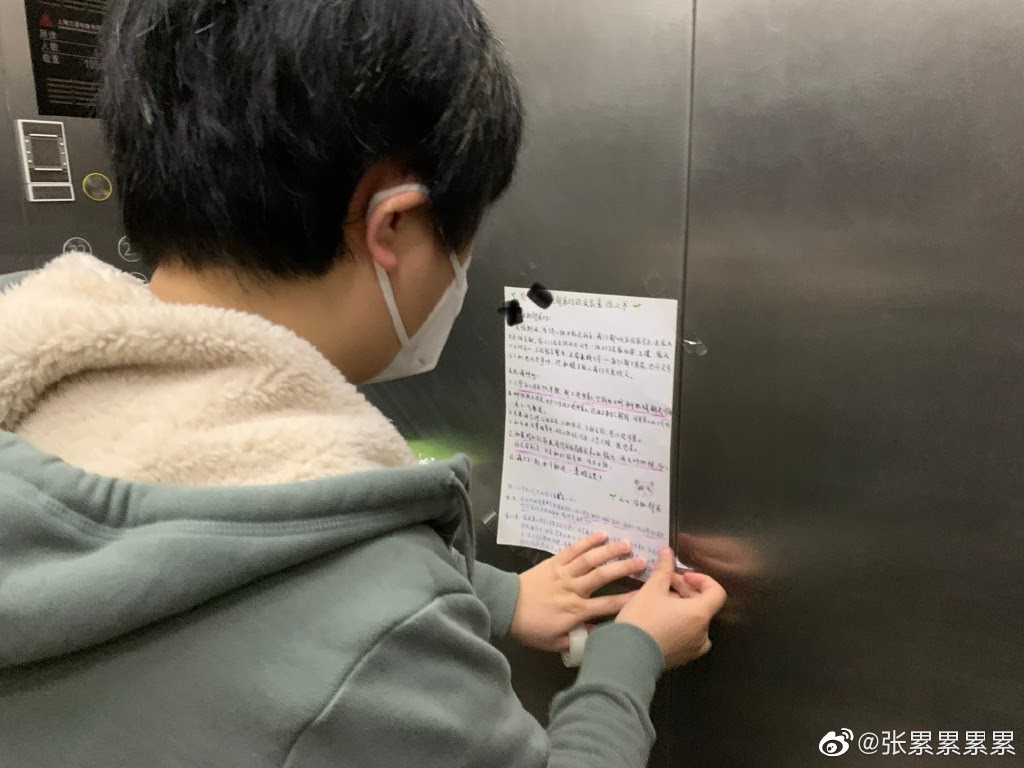

On a positive note, though, as more and more individual reports of domestic violence surfaced on Chinese social media in the past few months, a number of feminists, activists, and ordinary women campaigned to encourage people to be extra aware and vigilant of possible cases of domestic violence. On Weibo, the hashtag “Anti domestic violence during epidemic” (#疫期反家暴# yìqī fǎn jiābào) has been viewed 3.5 million times. In another online initiative, hundreds of participants distributed self-made posters (in Chinese) in their neighborhoods, reminding people to provide community care for survivors.