Torture and wrongful convictions: Some good news amid the gloom

A Henan man wrongfully convicted of murder after a forced confession regained his freedom on Monday, April 1, 2020, after 16 years in prison.

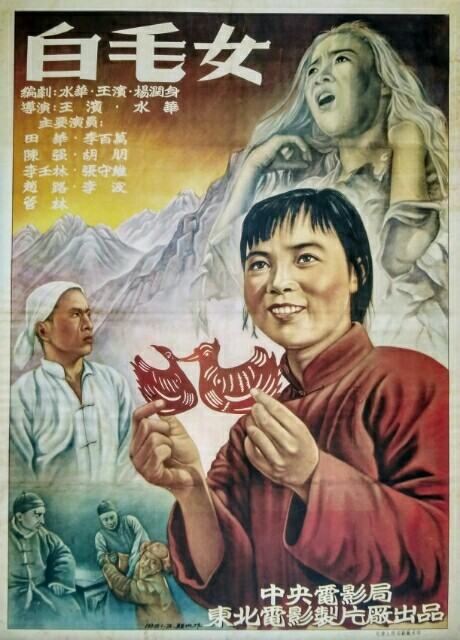

Wú Chūnhóng 吴春红 and family before his wrongful conviction for murder.

On November 14, 2004, Wú Chūnhóng 吴春红, a resident of Zhougang Village in Henan Province, clashed with his neighbor Wáng Zhànshèng 王战胜 over an electricity bill. The following morning, Wang’s two sons exhibited signs of having ingested poison. Wang’s three-year-old son died later that day. An autopsy performed by the local police department found 30 grams of an unspecified substance in Wang’s son’s stomach.

Within a week, Wu Chunhong was fingered as a potential suspect. He was taken into police custody on November 20. The police soon asserted that the unspecified substance in the boy’s stomach was miànzhà 面炸, a Henanese snack, and that it had been infused with tetramine, which is commonly used in China as rat poison, although it is banned there and in the rest of the world because it is also highly toxic to humans.

The Shangqiu Intermediate People’s Court, the municipal court with jurisidiction over Zhougangcun, convicted Wu of premeditated murder and sentenced him to death with a two-year reprieve on June 23, 2005.

If you read the court transcript, the case seems clear. The only problem is that Wu’s conviction was entirely based on his confession, which was elicited after undergoing physical and psychological torture.

Which is why this case is so vital to understanding how Chinese courts work. At the center of the case is the Chinese political-legal system’s continued reliance on coerced confessions.

Shackled and fettered

During a 2017 meeting (in Chinese) with Lǐ Chángqīng 李长青 and Jīn Hóngwěi

金宏伟, lawyers working with the Washed Grievances Network Xǐyuān Wǎng 洗冤网 on Mr. Wu’s behalf, he described the conditions under which he confessed:

“The police brought me to some place, I don’t even know. I got pushed into a room and a few people started kicking me. I was shackled and fettered at hands and feet. Then they got scared that they would scar me, so they took off the handcuffs and tied me to a bed with a rope. My feet didn’t touch the ground for two days.”

After the physical abuse, police threatened to lock his wife up if he didn’t confess, intimating the horrors she would face. He confessed.

Wu’s case centers on three areas where extensive legal reforms on paper have serious shortcomings, to continued tragic effect: torture, repeat confessions, and offsite interrogations.

Torture or phsyical abuse of detainees is illegal under Chinese law. But “coerced confessions are a real problem and everyone in the China criminal justice system is aware of that,” said Jeremy Daum, a senior fellow at the Paul Tsai China Center at Yale Law School, in a phone interview.

Daum explained that a sustained effort to reform laws relating to the exclusion of evidence began in 2010, partially due to a rash of wrongful conviction cases stemming from confessions coerced by abuse of some kind.

Legal reforms offer hope but don’t go far enough

After Wu’s 2004 case, “exclusion” laws have been enacted that exclude evidence collected through abuse or other illegal means from being introduced to court. Nonetheless, the continued absence of a “fruit of the poisonous tree” doctrine makes these reforms nearly meaningless.

The “fruit of the poisonous tree” holds that not only is any evidence obtained through coercive or illegal measures inadmissible, but also that all future evidence acquired through knowledge gained from the initial illegal interrogation is likewise verboten. Without such a principle, the temptation remains for police and prosecutors to torture to ensure swift convictions.

A second hole in Chinese exclusion law is the practice of taking multiple confessions. Wu declared his innocence during his first interrogation. After being tortured, he confessed on his second interrogation. During his seventh and final interrogation, he renounced his previous confession and reasserted his innocence. (He maintained his innocence during his entire incarceration, even rejecting a deal where his sentence would be shortened in return for acknowledging guilt.)

The problem with excluding a first confession induced by torture but admitting subsequent confessions is that a “suspect who has confessed once under torture is unlikely to understand that subsequent confessions might have a different legal significance or that torture won’t resume if his story changes,” according to Daum.

A final issue with Wu’s case was the location of his interrogations. Chinese law mandates that all interrogations occur within detention centers. At least one of Wu’s interrogations happened in an off-site location. Rules promulgated after Wu’s case also stipulate that defendants must be transferred to detention centers in a timely manner. Detention center interrogation sessions must be videotaped, which is an attempt to put checks on the police.

Yet all too often, legal reform is a paper tiger, powerful when promulgated yet lax when tested.

This case is, however, a hopeful moment in an arduous reform process. Daum explained that returning to old cases like Wu’s “sends a message to the public that they’re serious about undoing these past injustices.”

The bottom line is that a case like Wu Chunhong’s could still occur today, as efforts to remedy exclusion loopholes and end off-site interrogations have not been fully realized, and the practice of taking multiple confessions is still standard.

Wu Chunhong leaves prison after 16 years behind bars after a wrongful conviction.

A years-long letter-writing campaign spearheaded by Wú Lìlì 吴莉莉, Wu Chunhong’s daughter, was likely influential in securing the Supreme People’s Court’s attention to his case. Jin Hongwei and Li Changqing, his lawyers, helped her in writing. In total, they wrote between 600 and 700 letters to the Supreme People’s Court, the Supreme People’s Procuratorate, and other departments.

As China has a political-legal system, the courts and procuratorates are sensitive to public pressure. Likewise, many individuals believe that gross miscarriages of justice, such as in this case, are local issues that will certainly be rectified if officials at the highest levels hear about them. These simultaneous phenomena lead to the prevalence and (very) occasional success of letter-writing campaigns.

In an October 2018 note (in Chinese) written after the Supreme People’s Court ruled that Wu deserved a retrial, Jin Hongwei, who has an evident fondness for American film, compared the letter-writing campaign with Shawshank Redemption. He explained its importance, saying, “It’s a simple logic. This is your own problem. If you yourself are not extreme, what do you think the judge will assume?”

On April 1, the Henan High Court found Wu not guilty, stating that “the facts are unclear and the evidence is insufficient.” He was freed and returned to his home in Zhougang Village in Henan’s Minquan County.

Wu’s family plans to file for approximately 1.7 million yuan ($240,000) in restitution.

Online commentators were aghast (in Chinese) at the entire case. “Sixteen years! Destroyed a man’s life!” lamented one user. “Sixteen years of youth,” said another, adding, “The world has changed too much, how can he adjust when he gets out?” One user aptly summarized the online sentiment: “Ah…my heart hurts! Sixteen years of light .”

A screenshot from a TV interview with Wu Chunhong and his family.

In an interview with Fenghuang News (in Chinese), Wu Lili talked about the impact of her father’s imprisonment: “My dad’s biggest wish was that my little brother and I would study hard, and get accepted into a good school. At the time when my dad asked me why I wasn’t going to school, I said I just didn’t want to go. My dad cried then.”

After helping secure Wu Chunhong’s freedom, Jin Hongwei wrote in a WeChat essay (in Chinese), “There are those who compare appealing a case to a marathon. But the way I see it, at least a marathon has a clear endpoint. Appealing a case is more like Forrest Gump’s run. All you can do is keep on running. You’ll never know where the finish line is.”

After 5,611 days, Wu Chunhong’s flagrantly unjust imprisonment is now finished.

In a video interview from his home conducted by the Beijing News (in Chinese) that has over 400,000 likes, a sickly Wu Chunhong spoke out:

“I don’t want my family to endure any more bitterness.”

“I did 16 years. My youth is gone. The first half of my life was spent in vain.”

“Whoever wronged me must apologize.”