Rebel and momma’s boy: Mandopop star Jay Chou

Illustration by Derek Zheng

Chinese Lives is a weekly series that looks at notable figures from all eras of Chinese history.

It makes an odd contrast. The rapper swaggers provocatively to the beat in black snapback and white bandanna, framed by the pylons of a distant urban jungle, doing rhymes in slurred Chinese about why he always does exactly as his mother tells him. “Listen to Mom’s words / Don’t let her get hurt / Grow up quickly / To provide her protection.” Why would a rebel brag about being a momma’s boy?

But that’s Jay Chou for you.

Who is Jay Chou?

Born to two teachers in 1979, Jay Chou (周杰伦 Zhōu Jiélún) is one of the biggest stars of Mandopop in the past 20 years, a genius at blending styles and morals of East and West. In the early 2000s he exploded onto the music scene in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and mainland China, becoming an overnight sensation. His 2004 album Jasmine sold 2.6 million copies, an unheard of figure at the time.

Although his fans are aging (kids today are more into K-pop and the one-hit wonders of Produce 101 China), Chou still proves to have the magic touch. Last year’s “Won’t Cry” managed to break records, downloaded 100 million times in the first two days of sales. He even earned his own magic show on Netflix in March this year.

Why is he famous?

Jay Chou owes his success to his mother. Going against his abusive father’s wishes, his mother spent the family savings on a cello and piano when she noticed the boy’s talent for music. Lessons started for Chou from age 3. She bought him a tape recorder when he was older, which he carried at all times, absorbing the sounds he heard around him.

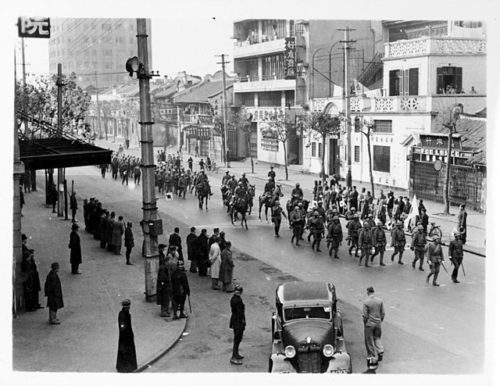

The times were changing fast. The 1970s to 1990s saw Chou’s native Taiwan saturated by Western hip-hop, rock, and folk music. At the same time, there was renewed interest in traditional folk songs after the Kuomintang lifted their ban on Taiwanese culture in 1987. By 1998, when Chou was discovered after shyly stumbling onstage for the TV show Super New Talent King, mainland China was ready for a change from Canto-pop (one-hit wonders channeling Madonna or Japanese music, with all the looks and none of the talent).

Chou isn’t a great beauty — Time magazine sketched him with “an overbite, aquiline nose and receding chin.” But that doesn’t matter. According to professor Anthony Fung of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, the craze for Chou came through his music. “At this time, China was embracing globalization but also had a keen sense of value of their own culture.”

Fung argues Generation Y wanted someone who balanced their desire for Western individualism with a continued need for “approval from society, parents, and teachers.” The government wanted a “safe” rebel/role model who attacked social problems and promoted traditional values, steering clear of Western rap artists’ political activism and pessimism. Both wanted something with a more “Chinese” flavor.

From 2003, this has been Chou’s raison d’etre, inventing a new style — Zhōngguó fēng 中国风 — blending West with East, new with old. He has appeared in Chinese robes to sing hip-hop concerts. He isn’t afraid to sacrifice the four tones of Mandarin for a speedy Western beat, infuriating purists by turning his lines to gibberish. But on the page, they read like pure poetry, rich in symbols from Chinese literature.

In his fantastical creations, East and West collide with specious ease — the barrage of rap and white noise that is the Bruce Lee-inspired “Nunchucks.” Dropping rhymes in fingerless hip-hop gloves while pulled through rice paddies on a rickshaw in “Fragrant Rice.” The ambitious marriage of R&B, the piano and classical guitar with the pipa, erhu and pentatonic scale in “East Wind Breaks.” Chinese music teachers set his work for students, fascinated by how it ties musical traditions together with a seamless and mystifying grace.

Chou ensured new genres became mainstream in mainland China. Although most Chinese hip-hop artists today wouldn’t credit his music for their inspiration, most of them grew up listening to him.

When asked by China Daily in 2006 whether he still listens to his mother, Chou responded, “Of course I do, of course I do. I think I’m still rather traditional, rather conservative.” Promoting family values comes naturally. In the early days of his fame, Chou lived with his mother, who organized his finances. The difficulties of growing up in a one-parent family may have made Chou feel he owed his creativity to his mother, needing to compensate her for years of suffering and struggle.

Hence why he wrote “Listen to Mother’s Words” and christened an album in 2005 Ye Hui Mei after her. In the same China Daily article, Chou said, “Filial piety is the most important thing.” Perhaps this is a good marketing tool: the main demand for pop music is from third-tier cities, where traditional family values are still strong.

It’s not that unusual for a Chinese pop star to write a song about their parents, grateful for raising them and lamenting the passing of time. But Chou’s popularity made him the perfect role model. In 2005, the Shanghai Municipal Education Commission placed his song “Snail” in school textbooks. Listeners are encouraged to do as Chou had done, not complain or resist the system, but crawl slowly up the ladder of life.

He’s traditional in other ways too — he doesn’t smoke or drink, according to his autobiography, Grandeur de D Major. Such abstinence earned him the chance to be the figurehead of a government anti-drugs campaign in 2014.

Musicians like Chou have allowed China to take hip-hop, rap, and R&B and make it their own, endowing it with tradition, stability, and feel-good values. His safe rebellion caters to the wants of both top-down and bottom-up.

Chinese Lives is a weekly series. Previously: