‘I Wish I Knew’: Jia Zhangke’s documentary is a rich collage of old Shanghai

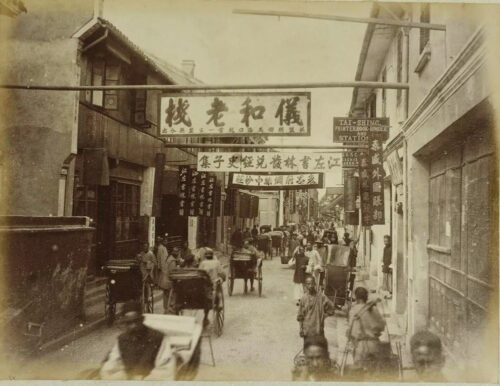

A story of modern Shanghai, told with stories from the past. Footage of modern Shanghai, with its flashy skyscrapers and restless crowds, collides with quiet, stationary interviews of times long gone.

Earlier this year, when movie theaters were still a thing, American viewers were treated to Jiǎ Zhāngkē’s 贾樟柯 I Wish I Knew (海上传奇 hǎishàng chuánqí) for the first time. Jia’s documentary, now a decade old, premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in 2010. Surprisingly, it was commissioned for the World Expo in Shanghai that year, with relatively free rein for what the iconoclastic director wanted to make. Rather than celebrating the port city’s economic and technological progress, Jia decided to look into the ruins of its past. I Wish I Knew features interviews with 18 subjects, compiling an oral history that largely recalls the city from the 1930s until the end of the Mao era.

Footage of modern Shanghai, with its flashy skyscrapers and restless crowds, collides with quiet, stationary interviews of times long gone. Between these segments, Jia throws in film excerpts, intertitles, and shots of his wife (and frequent collaborator) Zhào Tāo 赵涛 gloomily wandering through the city. The subjects, many of them elderly, are a diverse bunch. They talk about their childhoods, parents, and experiences in a Shanghai that no longer exists. They’re the children of artists, émigrés, gangsters, politicians, soldiers, and just ordinary people.

The stories the interviewees tell, set during the Second Sino-Japanese War, the Cultural Revolution, and other tumultuous events, are often tragic. Yáng Xiǎofó 杨小佛, the son of the social activist Yáng Xìngfó 杨杏佛, recalls his father’s assassination by the Nationalists in 1933. Xiaofo was driving with his father down the street when their car was ambushed by secret agents, carrying out a hit ordered by Chiang Kai-shek (蒋介石 Jiǎng Jièshí) himself. Another interviewee talks about his mother Shàngguān Yúnzhū 上官雲珠 and her political persecution in the 1960s. Shangguan, a brilliant actress who starred in The Spring River Flows East (一江春水向东流 yī jiāng chūnshuǐ xiàng dōng liú) and other classic movies, ended her life by jumping out a four-story window.

But not all the memories here are bitter and tearful. In the first interview, a man who was born in 1953 reminisces about the time leading up to the Cultural Revolution. He notes that the city’s crowded alleyways were a great place to play, and that, “Neighbors used to respect each other’s privacy.” Huáng Bǎomèi 黄宝妹, a former textile worker, tells about her meeting with Máo Zédōng 毛泽东 in the ’50s. The Chairman praised her work ethic, and she even got to play a fictional version of herself in a docudrama directed by Xiè Jìn 谢晋, the period’s greatest filmmaker.

A documentary about the history of 20th-century Shanghai would be incomplete without a mention of the city’s old film industry. During the ’30s and ’40s, Shanghai was the hub of Chinese-language cinema, producing a number of artistic, politically-tinged melodramas. Jia honors this link with various excerpts from older movies, along with interviews related to major actresses and filmmakers. Sometimes these clips are invoked to depict a certain event being mentioned, other times they’re used as a reflection of the interviewee and their subject.

Director Fèi Mù 费穆 and his masterpiece Spring in a Small Town (小城之春 xiǎochéng zhī chūn) (1948), for example, plays a key part through the interviews of two of the movie’s subjects. Lead actress Wéi Wěi 韦伟 relates the circumstances surrounding the movie’s production, while Fei’s daughter discusses her father’s premature death in Hong Kong and the trouble the family experienced in moving back to Shanghai. Other movie-related interviewees include actress/singer Rebecca Pan (潘迪华 Pān Díhuá), Taiwanese auteur Hou Hsiao-hsien (侯孝贤 Hóu Xiàoxián), and an assistant for Italian director Michelangelo Antonini’s ill-fated documentary Chung Kuo, Cina. (Chinese movie buffs can also look out for Hán Hán 韩寒, although this was years before he picked up a camera.)

While there are occasional intertitles that give background on the historical events mentioned in I Wish I Knew, I imagine the documentary could be difficult to follow for viewers not familiar with 20th-century Chinese history. There isn’t any rhyme or reason to the sequence of the interviews, which might reflect on the youth gangs or persecutions of the Cultural Revolution one minute before traveling back in time to bring up Nationalist rule, the opulence of ’30s Shanghai, or the Second Sino-Japanese War. With its wide range, I Wish I Knew gathers its disparate voices to present a rich collage of oral history. It’s a pivotal period of Shanghai told by the Shanghainese in their own words, assembled from a variety of times, perspectives, and experiences.

https://signal.supchina.com/the-life-and-work-of-jia-zhangke-chinese-auteur/