A song for Hong Kong, which I probably won’t sing

Historian Jeffrey Wasserstrom shares a personal story about music, mourning, and Hong Kong.

It was just one more bullet from one more gun

Now one more mad man’s deed’s been done

Why then does it feel like the death of an age?

When I wrote those words in 1980, I was a 19-year-old Californian spending a year studying at the University of London. I had been penning lyrics and putting them to music since I was 12, and I was toying with the idea of heading to Nashville after graduation to try to make it as a songwriter. This song was different than the others I’d written, though. It was the first inspired by a news story: John Lennon getting shot in Manhattan.

I occasionally played open mics in those days, but I never performed that song, despite thinking it was one of my best.

How many times can my heart break?

How many times despair?

When I think of a beautiful city

Where tear gas fills the air.

I wrote those words last June in Irvine, California, long after I had chosen an academic career over a musical one. I’ve written a fair number of songs, but never, until that one, another inspired by events that made headlines. Though I’ve only played a couple of open mics in the last decade, this song was one I eagerly wanted to perform — but only if I could do so in a specific city, one which had recently displaced London as my favorite. It was the city that inspired the lyrics: Hong Kong.

I thought I would get my chance last December, as I was scheduled to spend a week in Hong Kong to take part in a workshop. But other responsibilities took precedent, from meeting with journalists to checking out three protests, including a massive march on December 8, the biggest demonstration I had ever seen. I had also just finished writing a book, Vigil: Hong Kong on the Brink, that was about the local democracy struggle, and my paper for the workshop was on the subject of protest. Singing, unfortunately, had to take a backseat.

Postponing my Hong Kong musical debut didn’t seem like a big deal at the time. I’ve been going to Hong Kong pretty regularly in recent years, and during that December visit I was already scheming to get back there to do a launch event for Vigil (published in early 2020). What I didn’t foresee was everything that would happen next.

In light of Beijing’s new national security legislation for Hong Kong, which undermines the city’s autonomy, I’m less certain about being able to give a public talk about Vigil in Hong Kong in the future, or to perform a song about tear gas. I might be able to do both, but I am adding these activities to a growing list of things that I used to take for granted, but no longer do.

Given the kind of writing I do on taboo topics — such as Tiananmen 1989, whose anniversary we commemorate today — I’ve always felt there was a small chance I’d be turned away when flying into Beijing or Shanghai (though that hasn’t happened yet). With Hong Kong, by contrast, I’ve always been completely confident I would breeze through passport control — until some people with profiles not too different from mine got blocked recently, like academic Dan Garrett last September. My certainty level dropped to 98%, with 2% of doubt.

I used to be certain that a week spent in Hong Kong, unlike a week spent in the mainland, would be one where I’d encounter at least one political cartoon mocking the local or national authorities in a newspaper. I probably will still see it on my next trip, but with the satiric television program “Headliner” recently axed, there’s that 2% of doubt again. If I go to Chinese University of Hong Kong, will I see its facsimile of the Tiananmen movement’s Goddess of Democracy Statue, which I always make a point of saying hi to? Probably, but then again, I have 2% of doubt.

I might well be able to give a public talk about Vigil, but can it include critical comments about Xi Jinping? Can I fully shine a spotlight on figures currently living in Hong Kong who might be targeted for arrest under the new national security law? Similarly, playing my song at an open mic probably won’t be a problem, but the very possibility that it could be interpreted as seditious, that I could make things awkward for the venue, may make me think twice. The chilling effect is real. I am no stranger to pondering the consequences of my actions on others, as I consider this issue whenever I give talks on touchy subjects on the mainland — I’ve just never had to ponder such questions in Hong Kong before.

In Hong Kong’s dark new normal, it is hard to know what might be deemed unlawful. Songs are one form of expression the local authorities, with the backing of Beijing, seem determined to police, in part because music has been central to the protests. Various local songs — plus a rousing number from Les Misérables — figured prominently in the Umbrella Movement, and singing was even more important in the 2019 protests. A bill was just passed that criminalizes “disrespect” for the Chinese national anthem, and police have taken to tear-gassing groups that gather to sing “Glory to Hong Kong,” a song written last year that now serves as an anthem for the protest movement. Here are two verses in my Hong Kong heartbreak song that could make it dicey to play in public:

How many times can my spirits soar?

When the streets of the city ring.

With the sound of “Glory to Hong Kong”

And “Do You Hear the People Sing?”

How many times can my heart break?

How many times get the blues?

When across my screens, come the latest scenes

Of tragic Hong Kong news.

But there is another option.

If I do play a Hong Kong open mic, I could perform the song I wrote in 1980 instead, since Chinese censors tend to care less about artistic works that don’t address local issues head-on. And that old tune would be more than a little fitting.

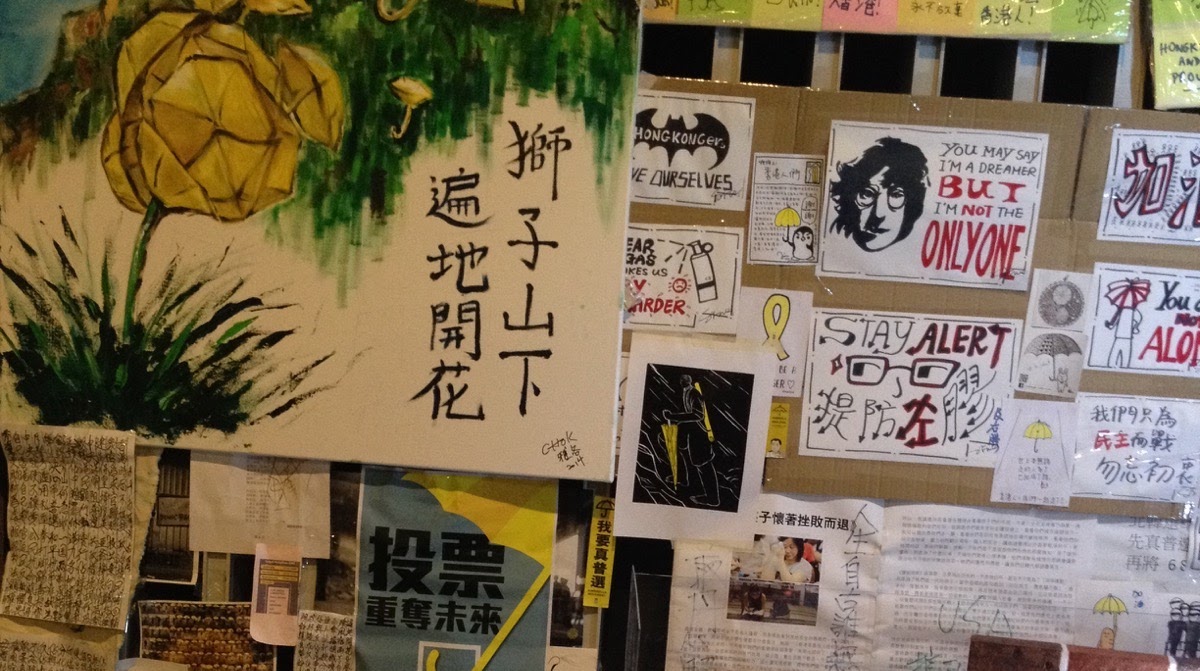

During the Umbrella Movement, some protesters were fond of quoting a line from “Imagine,” John Lennon’s most famous post-Beatles song: “You may say I’m a dreamer, but I’m not the only one.” Lennon’s name is also linked to a protest mode first popularized in Prague in 2014, i.e., the “Lennon Wall” — in Hong Kong’s version, people write messages and make drawings on post-it notes and paste them on walls all over the city, in multiple forms.

To commemorate Lennon at an open mic could be seen as meaningful, yet not dangerous. I could sing of feeling heartbroken about witnessing the “death of an age,” ostensibly referring to Lennon being murdered in 1980, but also clearly a reference to recent Hong Kong events.

It would also have an added layer of meaning for me. I don’t know if anyone else at the giant December 8 march was thinking about this fluke of timing, but December 8 was the 39th anniversary of Lennon’s assassination. This was on my mind when I passed a restaurant on the march route whose front window was covered with a kaleidoscopic array of post-it notes, a Lennon Wall in miniature. The crowd sang “Glory to Hong Kong,” a song I imagine the former Beatle would have liked.

Hong Kong’s people have continually shown an ability to defy impossible odds and create beauty even in the harshest settings. Still, thinking right now about how much riskier it has become to march through the streets, decorate windows with post-it notes, and sing “Glory to Hong Kong,” I am filled with sadness, and find it hard to see anything but darkness ahead for the city.

The chorus of that 1980 song I wrote, about the death of a person rather than a city, has taken on a new meaning:

Then my eyes are caught by the flashing headlines

I turn away at once wishing I’d have been blind

‘Cause I don’t want to read them, I don’t want to see what they say

Nothing’s sacred, nothing’s saved

Dreams just die, then they fade away

Least that’s the way I feel today

Jeffrey Wasserstrom teaches history at the University of California, Irvine, and is the author, most recently, of Vigil: Hong Kong on the Brink, which was published in February by Columbia Global Reports.