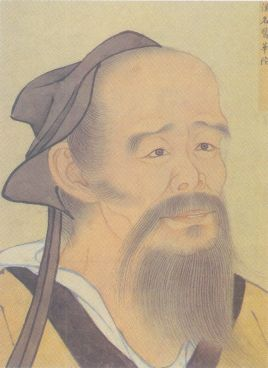

It’s the start of the 3rd century A.D. and China’s greatest surgeon is about to be executed. Before being led to his death, Huà Tuó 华佗 thrusts a manuscript at his jailer, saying, “This can preserve people’s lives.” But it was burned. None would follow in his footsteps, and surgery would become the withered appendix of Chinese medicine.

Who is Hua Tuo?

Hua was a man centuries ahead of his time. According to the 3rd-century Records of the Three Kingdoms, Hua was able to perform operations of extreme complexity. For example, he could open a patient’s abdomen, cut into the membrane-thin small intestines, clean them, remove damaged sections, and sew them back up again. Even by modern standards, it’s a perilous operation, risking fatal leakage of fluids into the abdominal cavity. But Hua’s patients would make a full recovery within a month.

If this and other stories can be believed — and, occurring in an age before antibiotics or knowledge of infectious bacteria, they should be taken with several handfuls of salt — Hua Tuo was an astonishingly gifted surgeon and acupuncturist. Even today, a talented doctor can be described as “Hua Tuo reincarnated” (華佗再世 Huà Tuó zài shì).

But the man appears to be a ghost. None of his writings survive. Estimates for his birth year fluctuate wildly between A.D. 108 and A.D. 190. Moreover, there are conflicting stories on Hua’s life — some believe he could even be mythical — the earliest (and most reliable) two being written within 200 years of his death in A.D. 208. They both say he was born in what is now Boxian County, Anhui Province. He also apparently loved books and read widely, feeling called to study medicine after witnessing the bloodshed that came with the shattering of the Han dynasty (206 B.C.–A.D. 220) into the legendary Three Kingdoms (A.D. 220–280).

Hua traveled to what is now Xuzhou in Jiangsu Province, intent on studying the Confucian classics. According to some of the conflicting stories on this part of his life, he got a degree and was offered prestigious jobs by the local rulers, but he refused each of them. Perhaps he, like other scholars, was horrified by government corruption during the fall of the Han.

How Hua learned his craft is a mystery. One tale purports that he traveled to Xuzhou and studied under a famous doctor named Cai. But legends sprang up about his gifts. One says he was given a book by two old men he encountered in a mountain cave, and was warned that the knowledge he found within would bring him nothing but trouble.

There was certainly a touch of the divine about him — texts claimed that even though he lived to be 100, he looked and acted like a sprightly 60-year-old. He attributed it to his abilities of “nourishing life.”

Some think Hua invented the “frolics of the five animals,” where patients seeking a cure for some ailment imitate the leaping of a tiger, the hanging of a monkey, or the lollop of a bear. The movements of these animals are represented today in the popular physical exercise and meditation practices of tai chi, and their prescription as a remedy is not unheard of.

Divinity could also stem from his terrifyingly accurate diagnoses, which bordered on fortune-telling. He could mix medicinal ingredients so well that he never needed to measure them.

His acupuncture was even more renowned. At a time when physicians favored large, thick needles that penetrated right up to the organs, Hua preferred something thinner that only went to the subcutaneous, fatty layer under the skin. This is still favored in acupuncture today.

It’s said that he used as few acupoints as possible, treating patients with pinpoint accuracy rather than a scattergun effect. There is an acupuncture meridian — on either side of the spine — named after him, along with a prominent brand of acupuncture needles.

Surgery

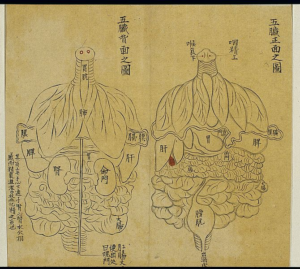

Operations were a last resort. In traditional Chinese medicine, the main influences on the body are the heavens and nature, and it is believed that disease is caused by the disruption of one’s life forces (气 qì and 阴阳 yīn yáng). Knowledge of anatomy wasn’t essential when an illness could be cured by externally rebalancing forces inside the body. An organ’s physical form was less important than the network it was part of or the forces affecting it.

This meant by the time of the Qing dynasty (1644–1912), China could produce highly accurate models of the body’s acupoints, and anatomy charts that looked like this:

In addition, Hua’s anesthesia was legendary. If his patients drank mafeisan (麻沸散 má fèi sàn) — an unknown recipe supposedly including hemp (a member of the cannabis family) and wine — they would fall asleep during his operations, which included the partial removal of a decayed spleen.

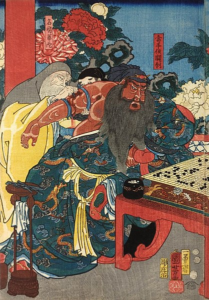

His most famous operation happens in the famous Chinese classic The Romance of the Three Kingdoms. Hero Guān Yǔ 关羽 (now immortalized as the God of War) is shot in the arm with a poisoned arrow in one of the book’s endless battles. Hua Tuo is sent to operate upon the great warrior, who refuses anesthesia and plays a game of chess, entirely unfazed while the doctor works, bystanders quailing at the sounds his knife is making as it scrapes against flesh and bone. The story became a theme in East Asian art, a credit to the strength of one and the skill of the other.

Hua died at the hands of the tyrant Cáo Cāo 曹操, who had seized power from the last Han emperor. Cao had stabbing headaches, which only Hua seemed able to cure, with a few well-placed needles. But then the story diverges — Cao may have begun to grow suspicious of Hua, who said he would have to operate on his skull to remove the pain permanently. Perhaps this was an excuse to murder him. Or Hua was reluctant to serve Cao and returned home, refusing a court summons by lying that his wife was ill and needed treatment. He was caught when Cao sent his henchmen to check.

Either way, he was thrown into jail and executed. His work was either burned by the jailer’s wife or by the jailer himself at Hua’s request.

After Hua, there’s no other famous surgeon in Chinese history. True, there is the occasional reference to a caesarean, and one slim volume of anatomical observations from the late Qing, but little else. Cutting open bodies was generally considered lowly and workmanlike, and Hua’s glorified status was an exception. Confucianism expressed horror at the mutilation of the body, which was ultimately the property of one’s parents. A patient’s duty was to keep it healthy, whole, and unblemished, since alterations would be a serious disability in the afterlife (the reason often given for China’s low organ-donor rate over the last 20 years).

With Hua Tuo’s execution, it seems that any Chinese tradition of surgery also perished.

Chinese Lives is a weekly series. Previously: