This Week in China’s History: Early November, 1911

On a momentous first Tuesday in November in the United States, let’s highlight a vital political moment in China: early November, 1911, when the first women’s suffrage organization was established, in Shanghai.

In her book Gender, Politics, and Democracy: Women’s Suffrage in China, Louise Edwards puts the founding date for the Women’s Suffrage Comrades’ Society at November 12, but her sources — and thanks to Professor Edwards for sharing generously with me — leave open the possibility that it was a few days earlier: in the first 10 days of November and maybe as early as November 2. Honestly, November 12 is probably the right date, but I’m going to exploit the uncertainty and connect our present to another moment when electoral politics was at the center of attention.

The Double-Ten or Xinhai Revolution began with the Wuchang Uprising on October 10, 1911, and events moved quickly that would bring about the end of the Qing Dynasty. Accounts of the revolution frequently focus on its sudden nature: plotters in Hankou’s Russian Concession accidentally detonate a bomb, forcing the revolt to begin ahead of schedule. Revolutionary leaders rush to catch up with events. Sides are chosen quickly. The airplane of the 1911 revolution is built while it’s taking off, it seems.

But as with many things that happen “overnight,” the 1911 revolution did not emerge from nowhere. People had been working for change for decades. Frequently, this movement is defined by men like Sun Yat-sen (孙中山 Sūn Zhōngshān) and Sòng Jiàorén 宋敎仁, but in the waning years of the Qing Dynasty, one of the most active groups was women wanting a fundamental restructuring of power in China.

Qiū Jǐn 秋瑾, featured in this column a few months ago, is usually put forward as an example of revolutionary women in China, and while she was one of the most prominent, she was one of many. This week, our focus is on a more institutional approach than Qiu Jin’s, women who sought the ballot rather than the bullet as means to political power.

~

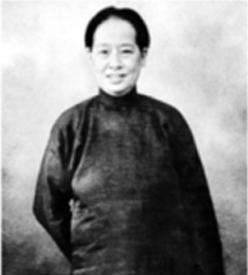

Lín Zōngsù 林宗素 first arrived on the public scene in 1903. She was active in a women’s association in Japan (where she met Qiu Jin, among others) and was one of three women who wrote prefaces for a nationalist/feminist tract called A Tocsin for Women (女界钟 nǚ jiè zhōng). Analyzed in Edwards’s book, A Tocsin for Women blended radical and conservative tendencies in its 87 pages. Written by (male) poet and scholar Jīn Sōngcén 金松岑 and presumed lost until the 1990s, the book presents a sweeping vision of women’s roles in a new China, from free choice in marriage to suffrage to holding the highest elected offices. At the same time, though, Jin’s program is clearly aimed at enlisting the support of women toward the goal of overthrowing the Qing Dynasty. All other causes, including that of women’s rights and suffrage, were subordinate to that.

In her preface, Lin Zongsu noted two weaknesses even as she supported Jin’s program. First, she worried that the goal of women’s rights can never be achieved “if we let Mr Jin alone plead on behalf of women.” Foreshadowing the decade ahead, Lin argued that women would never gain their rights “without shedding blood and overthrowing” the government.

When the Qing government finally did begin to topple, the debate over what would replace it began even as civil war spread across China. Just weeks after October 10, Song Jiaoren and others drafted a provisional constitution in the city of Ezhou, near Wuhan. The document reflected the ideals of Enlightenment liberal republicanism, with promises of equality, freedom, and democracy. Women, though, worried about its vagueness. Song’s constitution enshrined the equality of people before the law, but there was no guarantee that 人民 (rénmín, people) included women as well as men. Even if that were Song’s intent, this draft was just a start: would the eventual constitution for the Republic follow this interpretation?

To address these concerns, women’s groups began organizing to advocate for women’s suffrage in the new constitution. The first of these, established early in November 1912, was the Women’s Suffrage Comrades’ Society (女子参政同志会 nǚzǐ cānzhèng tóngzhì huì). A sub-branch of the Chinese Socialist Party, the Women’s Suffrage Comrades’ Society focused on educating and organizing women around the goal of attaining universal suffrage in whatever government followed the Qing.

This was not an abstract debate; time was of the essence. Even before the Qing’s last emperor had abdicated, Lin Zongsu was lobbying the provisional government that was established January 1, 1912. On January 5, Lin met with Provisional President Sun Yat-sen to ask that women be granted full political rights in the new Republic of China, and have a hand in its planning as well.

A new constitution would form the basis for government, but who would draft it? Elections were planned. Who would get to cast ballots? Lin and other women activists did not seek theoretical affirmation of the equality of people in this moment; they wanted political participation.

In these meetings, Lin told Sun that her group represented all Chinese women, and that they had undertaken study sessions and other means of preparation to educate and organize themselves so that they could be empowered and responsible citizens in the new role they were seeking. Sun was sympathetic, telling Lin that he would defend the right of women to vote against its critics. Emboldened, Lin Zongsu — who besides being a political trailblazer was also one of China’s first female journalists — printed her sense of their conversation in the newspapers almost immediately.

Louise Edwards notes that Lin’s goal was to legitimize her movement by demonstrating that it had Sun’s support, but the tactic may have misfired. Not all revolutionaries supported a political voice for women — including but not limited to suffrage — and opponents responded to the reported meeting with alarm. Zhāng Bǐnglín 章炳麟, who had been imprisoned for his revolutionary views, wrote worriedly to Sun, “I do not know whether women’s political participation would be good social custom or not,” and urged Sun to put the matter up for public discussion.

Sun responded by walking back some of the supportive comments he was reported to have made, saying that he had not made up his mind on the issue of women’s suffrage.

Debate over the new constitution ramped up as winter wore on. As the strength of resistance to women’s suffrage became clear, advocates intensified their organization. In February, Lin Zongsu’s Women’s Suffrage Comrades Association became part of a larger umbrella organization working for suffrage, the Women’s Suffrage Alliance. That group, led by Táng Qúnyīng 唐群英, carried the fight for suffrage through the adoption of the new constitution. The outcome of that debate and the reactions to what happened I plan to revisit here in March.

Lin Zongsu and her allies didn’t succeed, at least not immediately, in their goals, but their lesson is hopeful and cautionary. Hopeful because even in the face of stiff political opposition and enormous social pressure, they showed the potential and power of political organization. Cautionary because organization and good intentions were shown to not be enough. At a moment when democracy is under enormous pressure to show its quality, let neither of those lessons be lost on us.

This Week in China’s History is a weekly column.