According to Xú Bēihóng 徐悲鸿, by the start of the 20th century Chinese art was on its knees, a grand ship wrecked on the rocks of inertia. Like the country itself, China’s artwork had refused to innovate and move with the times. Xu did a lot to rectify this, and for that, he is now famed as one of the most powerful forces in modern Chinese painting.

Who is Xu Beihong?

An experienced artist who began practicing when he was six, courtesy of his father, who taught him portrait painting. In terms of the traditional “Literati” school that dominated China at the end of the Qing, Xu Senior’s trade was the lowest of the low.

Having learned the rudiments, Xu moved to Shanghai in 1915. He fraternized with modernizers like Kāng Yǒuwéi 康有为, who’d been a key instigator of the Hundred Days Reform in 1898 and advocated realism, modeling art after nature. He believed this a uniquely Chinese invention, taken back to Europe by Marco Polo. That it was abandoned during the Yuan dynasty was a result of imperial decadence and complacency. Yuan art was dominated by painters like Guǎn Dàoshēng 管道升, using landscapes to render what was in their heart — exterior realities bent to interior forces.

It spurred Xu to take a stand. In 1918, at just 23, he gave a lecture “On the Improvement of Chinese Painting” while teaching at Peking University. He’d adopted the New Culture Movement idea that art should replace religion as the dynamo of the nation’s soul. If the art was anything to go by, the nation was in trouble. Literati traditions meant learning through imitating the work of old masters, which stifled innovation completely. It had created a nation of “Suzhou emptyheads,” artists devoid of ideas, copying the interior worlds of long-dead sages. “The decline of Chinese painting has reached its nadir,” Xu said. “A civilization should never go backward. But Chinese painting today has gone back 50 paces from 20 years ago, 500 paces from 300 years ago.” If China was to face its problems, it needed to get its art out of the dreamscapes of the past.

Xu wasn’t the first to suggest reforming painting. The Shanghai school had tried to strip away the complex layers of symbolism of Literati painting, while the Lingnan school utilized Western bright colors and perspective.

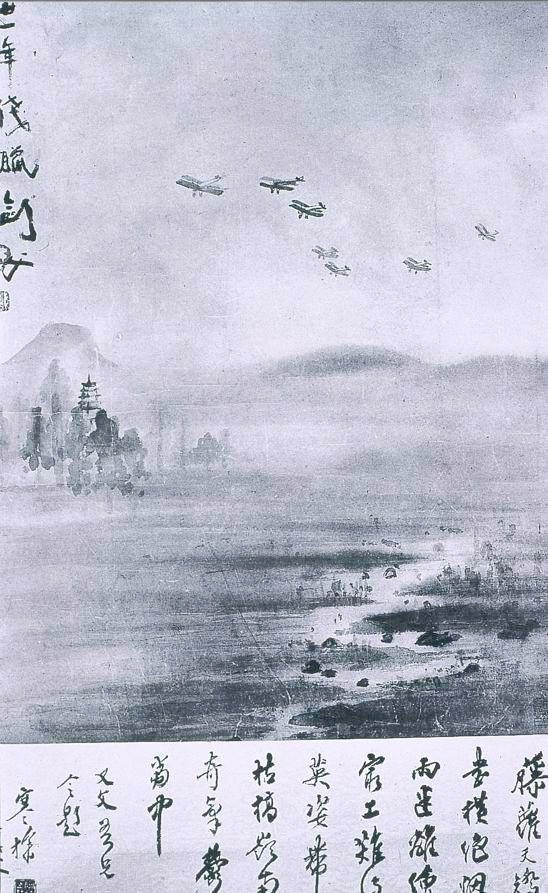

So during this period, modernity was making the occasional cameo…

…but the template hadn’t really changed.

Xu was the first to suggest a replacement: Western realism. That included oil painting, mathematical perspective, and scientifically-perfect depictions of human anatomy. “Artists, like scientists, are guided by the search for truth. Just as mathematics is the basis of science, figure drawing provides the foundation for art.”

This was confirmed to him by 10 years in Europe, studying the work of minor late-19th century realist painters. Paris was his haunt of choice, choosing mentors who told him to “perfect painting the human form in oil. Study every part, working to embody the subtleties. Do not simply make something that dazzles the eye.”

But not all Western art was good. He rejected Cézanne, Renoir, and Matisse as a mere fad, an indicator of a new European obsession with “sensationalism” and “fashion” since the Great War. “It is my hope that our national arts will uphold what is noble and good and that we shall continue to reject fame and financial gain,” said Xu in a letter to a friend in 1929, “so that the merchants of this world will not be able to play their wily tricks.” No doubt China’s humiliation in the previous century at the hands of Western merchants was in his mind.

This put him in the strange position of being both progressive and conservative — an artistic revolutionary, but still to the right of those who favored Western modernists, like poet Xú Zhìmó 徐志摩.

Upon his return to China in 1927, Xu began implementing his views as an art school teacher. His most significant post was as director of the Beiping Art Academy from 1946 (now the Central Academy of Fine Arts, the country’s premier art school). In contrast to the Republic’s main schools in Hangzhou or Shanghai, which continued copying old masters or Western modernists, Xu chose a different route. He insisted his students study life drawing for two years, like in Western art schools. This caused consternation from concerned conservatives, but would become the foundation for all Chinese schools.

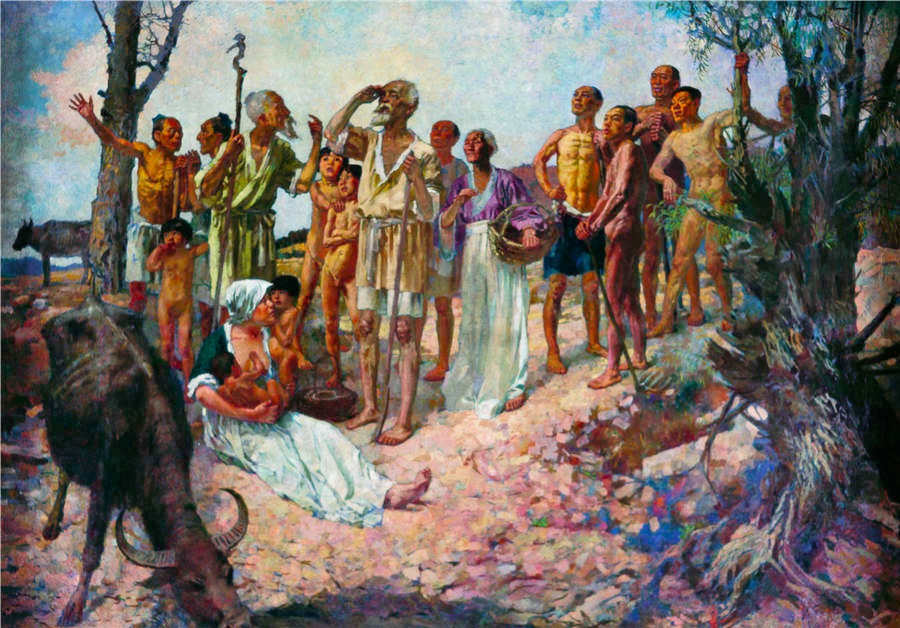

His own work was based on realist principles. During the War of Resistance, he was deeply concerned by the suffering of the Chinese people and the ineptness of the KMT government. He worked this into his creations, vast oil canvases based on ancient Chinese legends and history, rich in detail and devoid of the empty white space typical of Chinese art.

Despite being a modernist, he couldn’t resist the tradition of using Chinese history to talk about the present. “The Foolish Old Man Removes the Mountains” (愚公移山 yú gōng yí shān) is based on an ancient legend — one old man may not be able to move a mountain in his own lifetime, but he can succeed if his progeny keep at it. It tells of the importance of teamwork and perseverance in the fight against Japan. The canvas bursts with energy, Xu believing movement represented a change from the stilly inertia of Literati art.

“Awaiting the Deliverer” was painted after the Japanese invasion of Manchuria, showing ordinary people waiting expectantly for a strong leader after the overthrow of the tyrannical Xia dynasty (or the fall of the Northeast to foreign powers in the 1930s). Xu bustled through India and Southeast Asia, using his paintings to drum up support and raise funds for the war effort.

No matter how hot the war burned, Xu was confident China would rise from the ashes. His paintings of wild horses, boldly sketched with ink and brush, dashed off in the middle of the night after news of a stalemate or defeat in battle, are full of the energy he believed the country still had. Today the galloping horse is a symbol of the courage, hope, and resilience of China during that war — making an appearance on postage stamps and in modern blockbusters (like 2020’s The Eight Hundred).

Xu retained his post as President of the Academy despite the KMT moving against him for appearing too critical of their rule, and his school’s inadequate teaching of traditional Chinese painting.

He wasn’t a communist at that time — he admitted in a 1949 essay that he hadn’t fully embraced the masses in his previous works and had created elitist art for art’s sake. But Máo Zédōng 毛泽东 and Zhōu Ēnlái 周恩来 admired his work: his realism fell into line with their belief that art should be practical and accessible. They signaled that they wanted him to stay in Beijing once the capital fell. He was present on Tiananmen Gate when Mao proclaimed the People’s Republic of China, and was made Chair of the China Artists Association.

His position then changed dramatically. As the head of Beijing’s primary art school (soon answerable only to the Ministry of Education), he was at the top of the art education pyramid, his training in realism becoming the country’s future template for socialist realism under Mao. He further adapted the school to the demands of the new regime, proposing a “leadership portrait painting class” which he personally oversaw, also starting monumental works on Chairman Mao and the people. He went down to Shandong to experience life at a building site.

His work has been criticized since the 1990s. A new generation of scholars sees his work as a form of cultural imperialism, an unimaginative imitation of conservative Western art, designed to stamp out China’s cultural traditions. But thanks to his role in the foundation of the CCP, and all the propaganda artists that flowed from his schools, his name was cemented in the national mindset. He gave them visual evidence that China had woken up to reality.

Chinese Lives is a weekly series.