Transgender teen missing after forceful admission to underground psychiatric clinic

It’s been over two weeks since Zhāng Xiǎoqián 张小乾, a transgender youth from Weifang, Shangdong Province, was cut off from the outside world entirely for so-called “conversion therapy,” a harmful and discredited practice intended to alter gender identity.

It’s been over two weeks since Zhāng Xiǎoqián 张小乾, a transgender youth from Weifang, Shangdong Province, was cut off from the outside world entirely for so-called “conversion therapy,” a harmful and discredited practice intended to alter gender identity.

No one knows exactly where she is and whether she’s dead or alive — except for her abusive parents and staff members at the therapy camp. The last time Zhang was in contact with anyone else was on November 29, when she cried for help in a series of text messages to friends. Calling for their “urgent attention,” Zhang said she had been taken away from her home in Weifang by three strangers who “claimed to be police officers.” After seizing Zhang’s cell phone as “evidence of fraud,” the self-proclaimed law enforcement officers drove her to an unidentified location in Jinan, the capital of Shandong.

“The vehicle they are driving now is not a police car. They are not wearing police uniforms,” Zhang wrote. “They barely talk. They told me their job was to pick me up.”

Earlier this year, the 18-year-old teenger made the life-changing decision to transition, and started taking hormone treatments, but she did not come out as trans to her parents. In early November, Zhang, using the pseudonym Kěchéng 可橙, began chronicling her journey of transition in the form of an online journal.

But it didn’t take long for Zhang’s parents to discover her use of pills and intervene in order to change her mind. This caused Zhang to run away from home for a brief period of time in mid-November, during which she wrote a letter to a close friend, telling the trusted acquaintance to call the police if she fell out of contact.

“As someone who grapples with depression, if I go missing for more than 24 hours, there’s reason to suspect that I’ve killed myself or died from domestic violence inflicted by my parents,” she wrote.

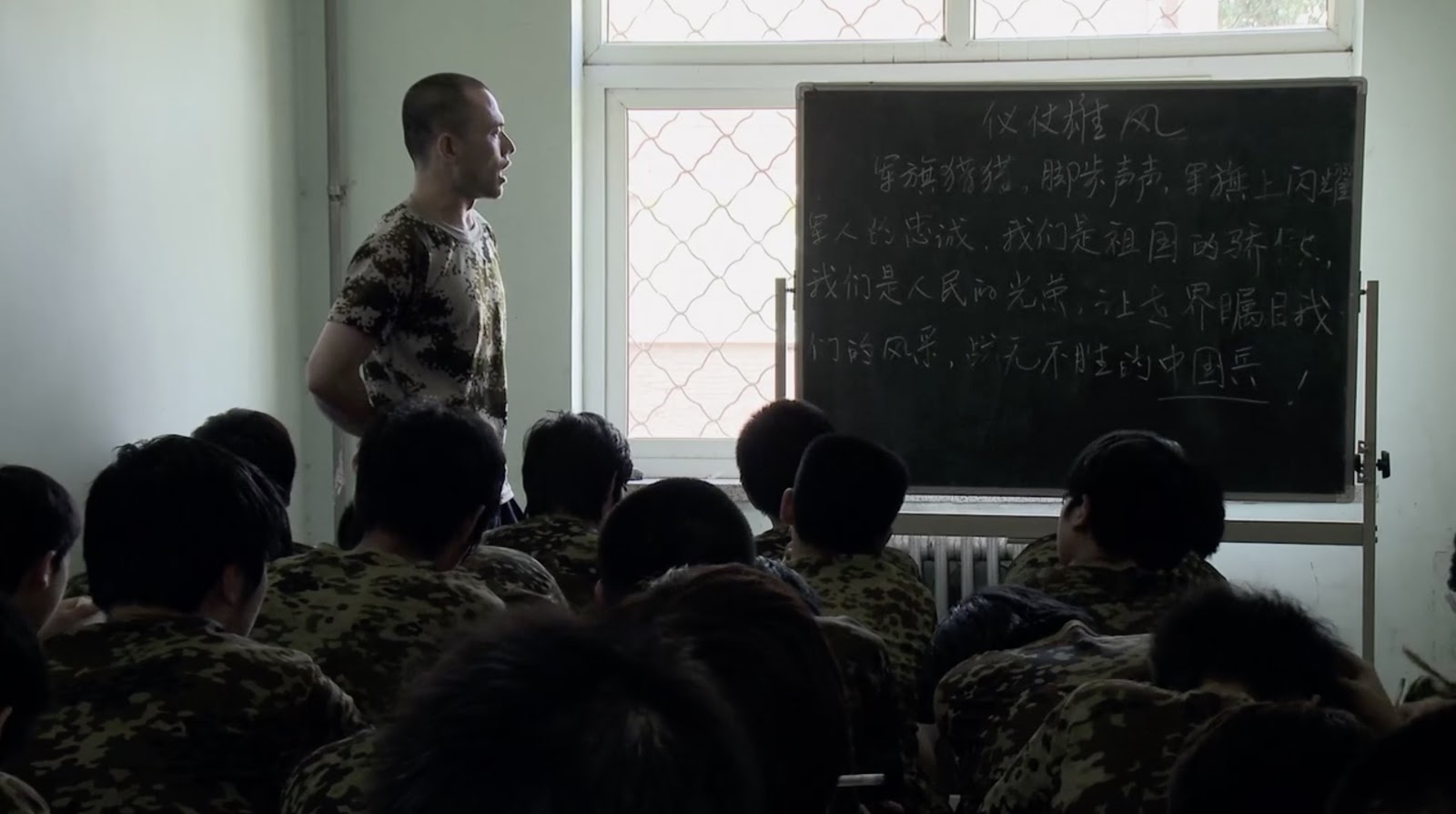

Concerned about Zhang’s sudden disappearance, a small group of advocates for the rights of transgender people gathered online and began investigating. According to Fengmian News (in Chinese), the volunteers believed that Zhang was sent to an underground “behavior correction” facility for “troubled youth” in Jinan. The “clinic” is notorious for using abusive measures to “cure” homosexuality and addiction to computer gaming.

The volunteers told the publication that Zhang’s case was particularly precarious given that the clinic she was admitted to has a well-documented history of using extreme methods — such as electroshock treatment, forced medication, and physical punishment — to force changes on its “patients.” In a lawsuit launched in 2019 by a woman in Jinan, the facility was accused of causing serious injuries to the plaintiff’s son during his six-month stay at the clinic. In March, a court ruled in favor of the mother, requiring the clinic to return a “tuition” fee of 27,500 yuan ($4,206). However, the legal trouble didn’t stop the facility from admitting new students or practicing pseudoscientific “conversion therapy.”

The volunteers also noted that their intervention was negatively impacted by the inaction of local police. When trying to file a missing person’s report with a police bureau in Zhang’s neighborhood, they were told that a case couldn’t be established because the teen’s parents, as his primary guardians, had the right to determine how to educate their son.

When confronted by the volunteers, Zhang’s parents constantly changed their stories and refused to disclose the teen’s location. Their behavior suggested to the volunteers that they wanted to cut Zhang’s communication with the outside world and deny her access to the psychological and physical care that she needed as a transgender person.

Forced “conversion therapy” is a serious challenge for LGBT+ youth in China despite scientific evidence that it is both dangerous and ineffective. After coming out to their homophobic or transphobic parents, sexual minority adolescents often face mental or physical abuse at home. Like Zhang, many of them end up being sent to conversion programs and surrounded by so-called professionals tasked to change their gender identities.

On a larger scale, transgender people in China remain vulnerable and underrepresented, and face discrimination at work and violence in their home. But in a monumental victory for the community, a transgender woman in Beijing won her case against Chinese ecommerce platform Dangdang this year, after the company fired her when she took a leave of absence for gender reassignment surgery.

Zhang remains out of contact with her friends and the volunteer investigators who have been trying to track her down.