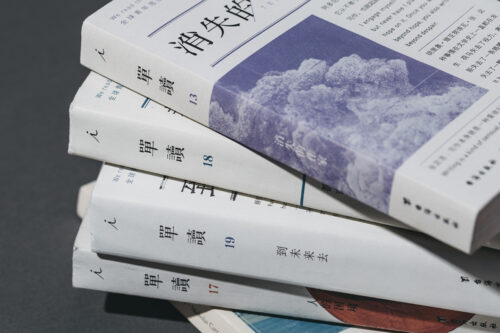

Life is really a book, / The content is complex and the weight is heavy, / It’s worth turning to the last page you can turn to, / And it has to be done slowly.

—Shen Congwen

Nestled in the crook of the Tuojiang River and backed by the Nanhua Mountains, stands the walled fishing village of Fenghuang in Hunan Province. It’s a cobbled time-warp, wooden stilt houses jutting onto a lime green river, framed by pine-clad hills. Aside from being picturesque, it’s famous for its best-loved son: Shén Cóngwén 沈从文, a prominent modernist writer who spoke for the rural world, relishing the idyllic purity of the timeless, complex lives of local artisans and peasants.

Although he wrote a plethora of tales, he’s forever fixed in the Chinese imagination for his soaring descriptions of the rugged, mysterious bandit-country of western Hunan. But his inability to condemn the old-fashioned ways of the countryside or to crowd his rural world with politics earned him a rough ride after 1949.

Who is Shen Congwen?

Shen grew up in Fenghuang, born to a soldier father on December 28, 1902. His parents hoped, given he was bright, that he would become a bureaucrat. However, his days wandering the hills with gangs of boys and “playing truant” put an end to that. Later, Shen expressed no regrets about this, declaring school “unspeakably boring,” instead yearning to learn “about life outside my own” through experiencing what he called the “big book” of life, rather than the “small book” of scholarly theory. Being beaten by teachers was a bonus, as it allowed him to escape into his imagination, a world filled with “a skyful of kites, golden orioles singing in the hills, trees laden with fruit.”

In his later stories, he frequently expressed the hopelessness of transcribing from the natural world into a small book of letters and recollections — art was only ever a feeble imitation for the inexhaustible variety of life. Instead of imitating, he tried to record: the material for much of his 200 short stories and 10 novels came from his Hunanese childhood.

Also his military adventures. A tradition in west Hunan was that boys should go into the army – perhaps it would also help his family, left penniless once Shen’s father fled to Inner Mongolia after being part of a failed assassination plot on Yuán Shìkǎi 袁世凯. From 1917, Shen served in a band of guerilla fighters during the turbulent warlord era, obeying Sun Yat-sen’s (孫中山 Sūn Zhōngshān) order to “pacify the countryside,” ridding it of bandits and regional warlords for the security of the nation.

But goals written in the little book changed dramatically when transcribed to the big book. Shen later wrote apathetically in My Education that his life became an ignominious cavalcade of drunken feasts, recording confessions made under torture, drills, and executions. Were poorly paid government troops who extorted money from their prisoners really any better than the bandits they guarded against?

Traveling through the various villages and towns of west Hunan, he gained further experience and knowledge of the book of life. He also worked as a police clerk and then a tax collector, in the process learning from an uncle how to write in classical Chinese, thus starting down the road of scholarship.

During his peregrinations, he met a printer who introduced him to the strange world of the New Culture movement: an ideology of Westernization and artistic reform launched during China’s century of humiliation. It led him to Beijing in 1923 — but a primary school diploma being his only qualification, and a poor grasp of punctuation, weighed heavily against him. He failed his university entrance exam, and as the coins in his pocket “were no longer sufficient to make a clinking sound,” he began life as a penniless writer, working out of a room converted from storing coal.

He started by eavesdropping at Peking University but ended the next year with his work getting noticed, published in the Beijing Morning Post. It was written in fresh and lively vernacular, a style which had just been declared the national language of China three years earlier, with much room for experimentation. He also read translations of Western romantic writers, adopting their styles. Prominent professor Lín Zǎipíng 林宰平 took him under his wing in 1925, declaring him a genius and introducing him to prominent modernist poet Xú Zhìmó 徐志摩. Around this time he also met modernizers Dīng Líng 丁玲 and her left-wing partner Hú Yěpín 胡也频 (together starting the literary journal Red and Black Monthly).

Unlike most of his intellectual friends, educated abroad and comfortably situated in first-tier cities, Shen Congwen saw how easily ideology could dissipate into violence at the grassroots level.

Once the printers moved south, the writers moved from Beijing too. Ding Ling, Hu Yepin, and Shen all moved to Shanghai in 1927. There writers fought to create a blueprint for the future of Chinese literature — Communists and Nationalists both believed it should be a tool for nation-building. But Xu’s clique (often called “The Crescent Moon Society”) was a disorganized coalition with little beyond the phrase “art for art’s sake” to bind them together. Shen seemed to hold little interest in political writing; unlike most of his intellectual friends, educated abroad and comfortably situated in first-tier cities, perhaps he saw how easily ideology could dissipate into violence at the grassroots level.

Xu introduced Shen to Hu Shih (胡適 Hú Shì), the latter so impressed with Shen he offered him a post teaching Chinese and western literature at Hu’s university (the China National Institute in Wusong). No matter his lack of qualifications, Shi believed Shen to have a brilliant future perfecting the vernacular style he’d launched. It was at this time that Shen fell in love with the dark beauty Zhāng Zhàohé 张兆和, who initially spurned his advances but was eventually won over by his tireless pursuits. Together they moved to Beijing in 1933. There, Shen, in a reverie of happiness, started his masterpiece, Border Town, and became editor of the prominent Tianjin magazine Ta Kung Pao.

Shen’s works are peppered with the local dialects, jokes, and ravishing backdrops of daily life in the valleys and peaks of western Hunan. The high snow-capped mountains which dive straight into the busy waterways, stilt-villages huddled by both banks. The angered swears of ferrymen punting up a torturous stretch of water, fury building up over generations until they’re just called the “Fuck-Your-Mother” rapids. The joys of hunting cooing turtle-doves, who start the day hidden in bamboo groves but end it on a dish fried with chilies.

He can appear paradoxical. Although a modernizer, he often defended tradition. A town executioner’s farcical reenactment of a pointless ritual to appease the city god in the short story “The New and the Old” (1936) is a “carefully preserved” ceremony that serves to make men and gods “cooperate” to keep the peace, only becoming pointless once belief had vanished under the Kuomintang, leaving the empty shell of ritual. The arranged marriage of the eponymous 11-year old to a toddler in “Xiaoxiao” (1929) is justified by Shen as an economic necessity for two poor families. His defense of prostitution in “The Husband” (1930) is that “it holds the same status as any other work, being neither offensive to morality nor harmful to health.”

He saw pros and cons to old and new. Many of his stories feature young peasant women led astray by the monotony and stupidity of traditional rural life, or else the fast living of regional cities and the lure of a New Culture education. The big book of life allowed for all sorts of scenarios, rarely aligning with a scholar’s philosophies — what mattered to him (as he put it in a manifesto of 1936) was only “the worship of the human spirit.”

Burning the big book

The War Against Japanese Aggression saw Shen Congwen turn against the KMT, believing they had handled the war badly (plus they had executed Hu Yepin in 1931). He returned to Beijing to teach at Peking University, having spent the majority of the war in the makeshift campus of Lianda, deep in the Yunnan mountains.

His apolitical writing irritated the Communists, who claimed a monopoly on knowing how the peasantry (the base of the coming revolution) acted and thought. They also disliked his frank depictions of the easygoing relationships amongst nubile young peasants, leading Guō Mòruò 郭沫若 to brand it as little more than “soft porn literature.”

Naturally, his writing career ended abruptly when the Communists came to power in 1949. He was abandoned by old friends: Ding Ling took a position at the Chinese Writers’ Association and criticized him for supposedly having upper-class ambitions. He was prevented from writing, disappeared from textbooks, and was forced to publicly confess that his writing had “no sense of life” and was “of no use to the people’s revolution.”

He attempted suicide by drinking kerosene and slitting his wrists and throat with a razor blade. A diary entry from May 1949 read: “I want to shout, I want to cry, I can’t think of who I am; where did the previous me go? The pen in my hand has suddenly lost its color. It’s as if every word is frozen on the page, their connection to each other broken. Their meaning lost completely.” He had no place in either Chinese state: his books were burned on the mainland, and also banned in Taiwan, as he’d chosen to stay behind, still distrustful of the KMT.

By 1950, he found a new calling as a cultural historian, working at the Palace Museum in freezing conditions over his magnum opus, Research on Ancient Chinese Costumes, a history of Chinese clothing. But this became “a big, poisonous weed” during the Cultural Revolution. His house was raided three times, all his manuscripts and papers burned. He was assigned to clean toilets at the Institute of History and was publicly denounced (his most feral denouncer one of his own protégés).

As an octogenarian in the 1980s, he became the center of a Renaissance, with notable academics from overseas re-introducing him to the mainland, Jeffrey C. Kinkley praising how he “labored tirelessly to rework the modern vernacular into a literary language figuratively as rich as Classical Chinese.” He found favor with Chinese academics, too — Shen “can discover the possibility of beauty within even a jumbled pile of rocks” wrote critic Liu Xiwei.

He was invited to lecture in the U.S., all the while making additions and alterations to his primary work from his tiny book-crammed office in the Chinese Academy of Sciences. But he received so many visitors, anxious to see a living relic of Republican China’s intelligentsia, that his wife had to put up a sign pretending he’d come down with a contagious disease. Even in his final years, too ill to hold a pen, he’d dictate work to secretaries. If he’d lived a few months beyond May 1988, he’d have been the first Chinese to win the Nobel Prize for Literature — which couldn’t be awarded posthumously.

State media published a dismally small obituary: Shen had lit up even the smallest cameo characters through a few quick strokes of backstory, but was dismissed with one line, pigeonholed as a “famous Chinese writer” by some hurried hand.

But he’s been popular in China ever since — Weibo is dotted with romantic and insightful quotes from his work, his texts are taught in schools across the country, and his stories inspired a new generation of Chinese authors (including Mò Yán 莫言) to search for the humanity found in rural areas.

It’s a victory for Shen’s apolitical stance. While China had been reaching for the latest manuals on modernity and ideology, he’d been drafting from the big book — a messy and inconsistent book, perhaps, but a tome that stayed on the shelf long after those neat little “small books” went out of date.

Chinese Lives is a weekly series.