‘Only when you, your children, and your grandchildren become Chinese’: Life after Xinjiang detainment

“They said there was a document sent from above, from the administrative center, and that they were acting based on that document. They said no one can change the document since it was sent from the Central Committee. They said that the current system would not change until all Muslim nationalities would be extinct.”

In early 2020, just as COVID-19 was beginning to sweep across China, I traveled to Kazakhstan to interview Kazakhs and Uyghurs who had recently fled across the border. In a cold second-floor office building, I met dozens of China-born Kazakhs who came to talk to researchers about their family members who were lost in detention facilities in Xinjiang. I also spoke to nearly a dozen former detainees about their experience, and how they were struggling to recover their sense of self. I was not the only researcher there. Journalists and filmmakers from around the world gathered in Almaty. A pair of filmmakers I met, Yadikar Ibraimov and Jack Wolf, agreed to share with me a film project they were producing — parts of which are featured in this essay. The film conveys the urgency of the ongoing trauma that is palpable in Uyghur and Kazakh exile communities, particularly in Kazakhstan, where the stories of new arrivals and regular outpourings of collective grief have begun to shape daily life.

An interview Ibraimov and Wolf conducted with Nurlan Kokteubai, a 56-year-old Kazakh teacher from a village in Chapchal County, right at the China-Kazakhstan border, typifies the raw honesty and blankness that I have found state violence engenders in its targets. As the son of a village leader and someone who completed nine grades of education in addition to two years of training in childhood education, it made sense that Nurlan and his wife, who he met at a nearby pedagogical institute, would become leaders in their community. Like most Uyghur and Kazakh villagers, he had no way of knowing that the “Open up the West Campaign” that state authorities initiated to bring Han settlers and infrastructure development to rural Xinjiang society would result in a basic transformation of Kazakh institutions. Their education system, practice of faith, language, grassroots political structure, and even the integrity of their family units would be fractured, taken away, and replaced.

The trouble started in 1997, when Nurlan’s brother got into a dispute with a new Han Party Secretary over a financial debt. Nurlan recalled, “He couldn’t take revenge on my brother, so he decided to take revenge on me, and I was fired from school.” Nurlan spent a long time trying to get reinstated, but the local and regional administrators in the community took the side of the new leader. “They used to say that they would deal with the problem, but they were just stalling.” It was clear to him that as a rural Kazakh man who had been deemed guilty by association, he had no real power to regain the life path he had strove so hard to achieve. Through his petitioning he was also producing a record that could be construed as unsubmissive, of “refusing the management” of local authorities, item 16 on the list of 75 signs of religious extremism.

Since his wife’s parents had moved to Kazakhstan around 2009, drawn in by the incentives of the Kazakhstani government’s ethnic Kazakh repatriation policy, Nurlan began to think about starting a new life across the border. It seemed like a way to start over, in a space where Kazakhs were a population with civil protections. After his wife retired from her work at the school in 2011, they took the plunge. “We had good times then,” Nurlan recalled. “My children got citizenship and my wife and I had residence permits. And at the same time we did not lose touch with our place in Xinjiang.”

Then on May 30, 2017, the good times abruptly ended. Nurlan’s wife took one of her usual trips back to her old village, but this time her passport was confiscated. “Then they told me to come as well. So I went there on the 15th of August in 2017.”

When he arrived, he saw that conditions in the village had radically changed. The People’s War on Terror, which had primarily targeted Uyghurs in Southern Xinjiang, was now aimed at the Kazakh community, a population that the Xinjiang Public Security Bureau had not seen as a threat in the past. Something had changed. The “war” was no longer something that Chapchal County leaders simply pledged to support, it was transforming daily life.

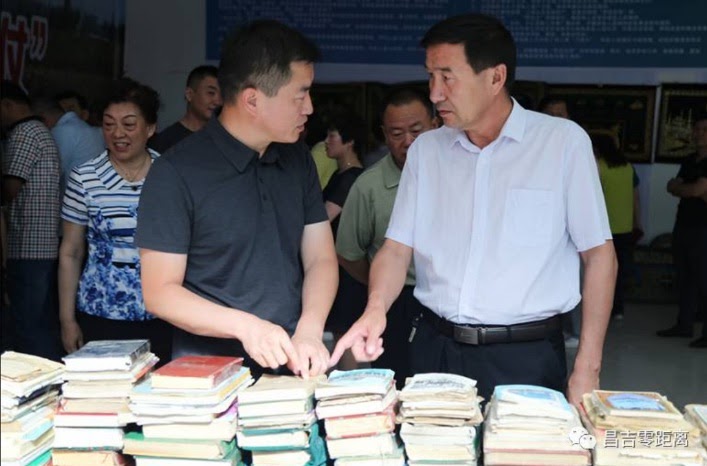

A new “Three Illegals, One Item” (三非一品 sān fēi yī pǐn) campaign had been instituted not only across Southern Xinjiang, where seizures and burning of Qurans, religious books, prayer rugs, and other materials deemed “extremist” began as part of related programs already in 2013. Now, Kazakh-majority areas in the North were also targeted. (“Three Illegals” refers to “illegal religious activities, illegal religious materials, spreading illegal religious networks.”) This new campaign demanded that villagers turn in small plastic pitchers used to wash one’s hands as part of daily hygiene — something possessed by nearly every Uyghur, Kazakh, or Hui household, particularly in rural areas where running water was not always available. Cups and plates with Arabic inscriptions or Uyghur calligraphy were also criminalized. Books that had previously been published with the approval of the Xinjiang People’s Publishing House, such as the children’s book A Letter from Saudi Arabia, were also banned as a manifestation of religious extremism — item 42 on the list of 75 signs of religious extremism. Possession of such objects could result in immediate detention. In September 2017, a survey of 300 Uyghur villagers published by the Ministry of Justice of the People’s Republic indicated that they believed perhaps 15 percent of the illegalized household objects had not yet been turned in or destroyed. Around 50 percent also confessed to thinking that fasting during Ramadan should be considered a personal choice.

A 2017 display of confiscated prayer rugs, criminalized books, seized household items and decorations associated with halal practices in Manas County, directly east of Nurlan’s village.

These quite normative forms of Kazakh and Uyghur cultural and religious life were suddenly deemed “anti-human, anti-society, and anti-civilization,” and together they harmed “social stability.” Nurlan recalled:

When I went to my hometown in August 2017, I witnessed the local government collecting and destroying books and other written materials in Arabic and Kazakh. Since my village is mainly Kazakhs, I’m talking only about Kazakhs here. A group of five people would come to each house and order you to take out all religious books and even those books about Kazakh heroes, as well as Abai Kunanbai’s books. They asked the homeowners to burn them in front of the government workers. They also took away the Turkish carpets, removed gravestones from the tombs, stopped Kazakh-language teaching, and confiscated all the imported products from Kazakhstan, especially candy, from the shops.

Yet despite this charged atmosphere, Nurlan was still hopeful that he might be able to return to Kazakhstan with his wife, leaving this all behind. Then, two weeks later, in early September, as Nurlan was working to get his wife’s passport back, he was called into the village police station. “When I arrived, I was told that I was involved in international terrorist organizations. They told me that they would take me to the educational center.”

What happened next was a blur. The police forced him to submit his biometric data. “Then they drove me in a car and took me inside. There was a signboard which said ‘reeducation center.’ I entered and laid in there.”

Yet, as he says in the video interview below, he was still not afraid. “I was not afraid since I did not commit any crime.” He thought it would all be sorted out, so he was not afraid at all. He had no idea that he would spend the next seven months in the camp. His time there was bewildering: beaten cell mates, patriotic songs, cameras everywhere, sirens in the morning, commands yelled over speakers, five-minute meals, bathroom breaks three times per day, trying to sleep in shifts.

For six months, Nurlan was not interrogated. He was simply treated like all the other “level three” detainees — a category that was the least severe. To his thinking, in many ways it was simply like being in prison. “There was no learning at all,” he said. “All we did was watch TV — broadcasts of only one channel, which circulated videos about Xi Jinping’s visits to numerous countries and how he was helping these poor countries develop. Nothing else. We didn’t learn any skills. We were given plastic stools and would wear plastic slippers. We had to sit absolutely still on the stools while watching the TV programs about Xi.”

The first six months were like torture. During his first month they gave him sleeping pills, since he could not fall asleep. Then he began to have chest pains and was taken briefly to the hospital. In November, he fainted again and spent 10 more days in the hospital. Then on January 8, 2018, he had a heart attack and was hospitalized for most of the month. But still he was not released, nor was he told why he had been detained. As he says in the video below, he felt his life, and the life of his community, slipping away.

You do not know for what crime they brought you there and you just stay there. So, I just stayed there. They used to tell us that we would never get out and that we would be sentenced, sentenced to five to 30 years in prison. They said that they would keep us there until our views changed, and if our views failed to change, they would always keep us there. They said they would keep us there up to 50 years, until the whole nation, Kazakhs, Uyghurs, and other Muslim nationalities, would disappear. They said there was a document sent from above, from the administrative center, and that they were acting based on that document. They said no one can change the document since it was sent from the Central Committee. They said that the current system would not change until all Muslim nationalities would be extinct. “Only when you, your children and your grandchildren become Chinese would the current system change,” they said. I was told not to think about going back to my family in Kazakhstan. They said it was impossible. So when you hear these kind of words, you feel sick and cannot sleep. These kinds of words were the most difficult for me to bear, even if no one beat me. That is why my heart started to hurt.

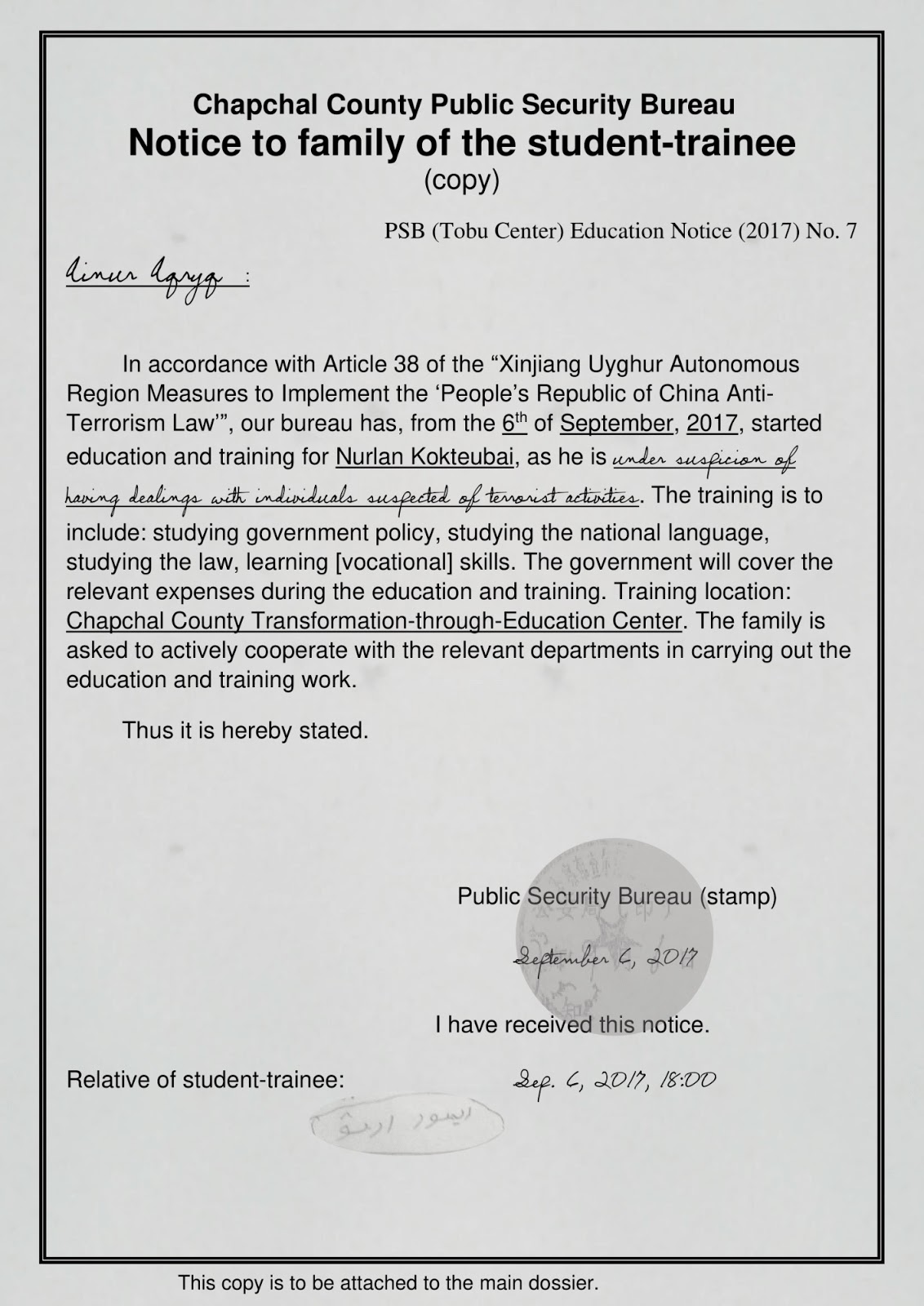

Finally, his family was given a backdated notice with a forged signature that gave a reason for Nurlan’s detention. It was only in early April 2018 that Nurlan was finally questioned about his alleged “terrorist” associations.

Backdated notice given to Nurlan’s family describing the reason for Nurlan’s detention. (Source: Nurlan Kokteubai; translation by Xinjiang Victims Database).

Immediately after his interrogation, Nurlan was provisionally released. He still remembers the surreal feeling of walking out through the black gate surrounded by high fences, the guards watching him from the other side.

For the next few months, he spent many hours each day studying Chinese. He copied out the 69 pages of the 19th National Party Congress Report twice — an effort that damaged his writing hand. Speaking in early 2020, he said, “Even now my hand does not function well.”

In the meantime, Nurlan’s three children in Kazakhstan had been petitioning the Kazakhstani and Chinese governments for his release. The Chapchal police told him to contact them and make them stop. But still his children persisted. “The police used to come every day, sometimes even at night, they did not let us sleep,” he recalled. “They said, tell your children to take back their petitions. So we used to go again and call them. Four people usually stood behind us while we did this. They wanted to make sure we said the things we were told to say.”

But still his children said they would not stop. In a phone call they told Nurlan — and the four people listening in — “If you committed a crime, let them sentence you and shoot.” The police told Nurlan that this was evidence that his daughter was indeed a terrorist.

Eventually, though, the pressure worked. On January 24, 2019, Nurlan was allowed to reclaim his passport. The village Party Secretary told him to silence his children as soon as he arrived back in Kazakhstan and to tell no one about what he experienced. He said that Nurlan’s wife would be allowed to follow him the next month after her paperwork was in order. On February 28, she arrived.

Over 2019, Nurlan thought a lot about what happened to him. He recalled how, many years before, he had been invited to attend a big meeting where star teachers were asked to give reports about their classes. “I remember how I presented my report there. I remember how the audience clapped and were grateful to me for my presentation. I still cannot forget those days. The Chinese government degraded such a person and brought him to his current condition.”

Nurlan also thought often about how, after his release, he was forced to stand in front of his neighbors and the broader community and confess to crimes he did not commit at the flag raising ceremonies that were held every Monday.

There were more than a thousand people and I had to say with a microphone that I committed a crime and that the government and the Party forgave me. They made me say that I would behave well from now on and fight for the Communist Party. I was forced to say that I would fight against two-faced dissidents. The hardest thing for me was to admit the crime that I had never committed in front of thousands of people. After that, people started to avoid me. After all of that, I think my attitude toward people changed. I became reluctant to talk to people. I started to prefer being alone. I am in this kind of status now.

Nurlan appears to be suffering from post-traumatic stress. He noted that he now frequently forgets basic things, like whether or not he paid for a taxi. He feels a kind of lethargy. He has lost a taste for the verve of life. It is hard for him to be interested in anything. He tries to write down his thoughts, but nothing comes. It is as though he is confronted with an unending blankness.

Usually when I cannot fall asleep, I go outside to smoke. I walk outside for a couple of hours and go back to bed. I smoke a lot these days. I have different thoughts. I see how I was detained and my previous life seems to be right in front of me, my previous happy life. I have never been in a fight with anyone in my life. I never swore at anyone. I have never robbed anyone. I have never lied. I have never taken money from anyone. So I ask myself, why would a man leading an honest life end up in this kind of situation?

Nurlan shares in common something that literary scholar Susan Derwin notes was experienced by Primo Levi and Jean Améry, “the intimate, if inarticulable, effects of victimization.” What he experienced feels unsayable. The words are just not there, yet it is all he can think about. He sleeps only an hour or two every night, images flashing through his mind. “I can hardly wait for the morning,” he said. All of this makes him feel detached from his sense of self and disillusioned with the possibilities of life. Even his children, the one thing that kept him going in the camp, no longer motivate him in the same way. “I no longer show any interest in things or miss anyone. You usually miss your children if you do not see them for a long time, but I have lost an ability to feel that. I have lost the feeling of urgency when I have somewhere to be. Now I just think, ‘Let it be.’”

One of the only things that continues to give Nurlan meaning is speaking to researchers and reporters about what is being done to Kazakh and Uyghur society across the border in China.

These people did not commit any crime. They only went to a Friday prayer in a mosque or went to Kazakhstan and then they were all accused of being terrorists. These innocent people are still there (in the camps) without committing any crime. I feel very sorry for them and I think about it often. When I think about each of those innocent people (I met), I cannot sleep. Some of them are dying, some of them are being sentenced to 20 years in prison.

Nurlan is also not hopeful that the system will change. He has seen how state power has created its own reality, the “truth” he was forced to confess in front of thousands.

They have meetings every day where they discuss the progress of the Party. They say that they defeated this and defeated that. They have defeated the United States in the trade war. Everything is a lie, but people take it as the truth. Everything they say is a lie. There is no other mindset there. Now all the Uyghurs in Xinjiang are seen as terrorists. All the Kazakhs are seen as terrorists too. I am telling you about what I have seen and what I know. I am telling you the truth as I have experienced it. I am telling you about how I lost my freedom. I am telling you about how my family was torn apart and about the condition of the whole nationality there. This is all I can say…I’ve actually forgotten most of the things I wanted to say.