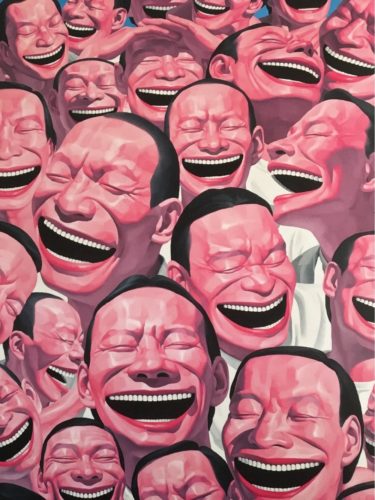

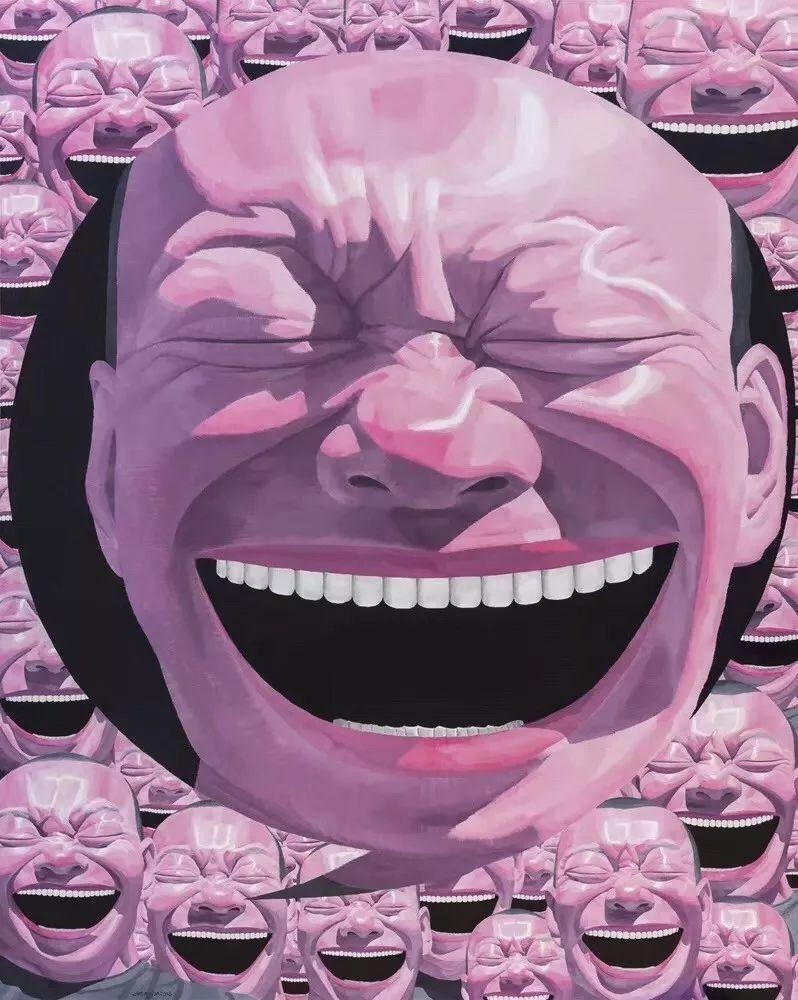

With leering features screwed up and stretched wide, a sheen of sweat on reddish skin and topped off with a shaved receding hairline, the faces cackle remorselessly. They get shot, do handstands, wear an array of odd hats, tumble through space, or just fill entire canvases, always with eyes closed and mouth agape in the throes of some unsettlingly ambiguous passion. Instinctively, the viewer searches for the cause, the emotions hidden behind — for something about them feels wrong.

Is this laughter an escape to a better world, or a reaction to the surreality of the new China?

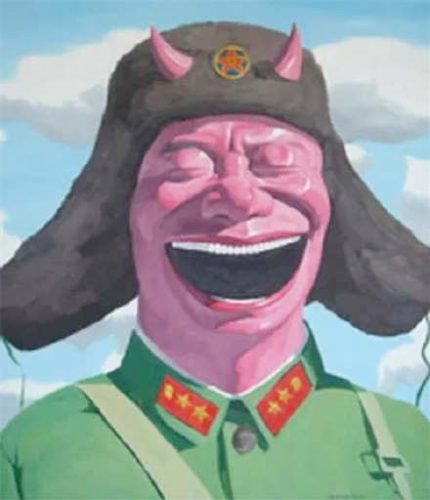

These are the 笑脸 Xiàoliǎn — “Smiley faces” — one the most recognizable facets of post-Tiananmen “Cynical Realism,” when Chinese artists were faced with the comforts of a consumer boom and renewed international trade on the one hand, and the legacy of broken political dreams on the other. The artist, Yuè Mǐnjūn 岳敏君, saw the solution in his own contorted face. His smileys are now found in the big metropolises — on statue installations in Hong Kong, or else hanging in the new He Art Gallery in Foshan adorned in the garb of PLA recruits (much to the fury of Chinese nationalists). For Westerners, the phrase “contemporary Chinese art” will most likely conjure up Yue’s cackling face (along with Ài Wèiwèi 艾未未). Western critics embrace him as a genius, given a retrospective at the Foundation Cartier in Paris in 2012; in 2007, Time Magazine said that “if the big-picture question of our time is what to make of China, this is the man to paint it.” But has Yue become a victim of his own success?

Who is Yue Minjun?

Perhaps surprisingly, given his output, Yue is a reserved, quiet man. When giving interviews, he spends little time talking about his personal story. He started drawing lessons at age 10, according to an interview with the Huffington Post. But we know he grew up within a peripatetic family of oil workers, sent from plant to plant during the Cultural Revolution.

“I cannot recall any event that has shaped my political views,” he told CNN in an interview in 2007. “But politics is everywhere in Chinese life, like the meal you eat every day.” Over time, the idea for the faces gestated within him. In an interview for the book Reproduction Icons: Yue Minjun Works 2004-2006, Yue noted that the culture of conformity under Mao meant “everyone had to do the right thing…which is why the act of smiling, laughing to mask feelings of helplessness has such significance to my generation.” Once China opened up in 1978, he learned about Western artists and styles through the new books that slowly trickled into the country. After graduating from high school in 1983, he went to work as an electrician, then moved to a deep sea oil rig off Tianjin for five years, where he started painting portraits of his co-workers.

The sudden realization that he was the oldest member of the team, aged 23, spurred him into action. He convinced his director to send him to art school, at Hebei Normal University. It was a bold and experimental time. In 1985, the “New Wave” pushed the boundaries of the movement, taking pride in discovery and innovation after decades of living under the heavy hand of the Great Helmsman. It saw recognition by the government — the 1989 China/Avant Garde exhibition at the National Gallery was unprecedented. They proudly called themselves the “no U-turn” movement — from now on, artistic and social liberalization could only plow forward, forever.

The state violently disagreed. Yue graduated into the melancholy fallout after June 4, 1989. “My mood changed at that time,” he told the New York Times in 2007. It may have looked like a bad joke — 10 years of liberal progress knocked off the rails, a return to the uncertainty and fear of the past. Would reform in China now ever really be possible? “I was very down. I realized the gap between reality and the ideal.” Many others experienced similar feelings of what he has described as a “profound sense of loss and disillusionment.” He fled to the new artist communes that sprang up around Beijing — first the one surrounding the old Summer Palace, then what would become the bustling Songzhuang art colony. The latter was cold, but the villagers provided a welcoming community, Yue living off just 200 yuan (about $30) a month. The colony was a loose band of misfits, so-called “vagabonds” without a stable job and place in society, occasionally raided by suspicious police and united by their shared desire for freedom.

At this time — in 1991 — Yue’s style was still unformed.

Yue knew it. “Before I produced these people [the smileys], I felt my art lacked power,” he said (quoted in Louis H. Ho, “Yue Minjun: Iconographies of Repetition,” Modern Chinese Literature and Culture). He remembered a work by Gěng Jiànyì 耿建翌 (The Second State) from the 1989 exhibition, which consisted of four faces cackling jubilantly, but these laughs “were not quite right, in which meaning had been inverted, and expressions turned upside down.” Something clicked. “I drew one person, and then added another and another until there were crowds of them.”

His smiles would only make headlines in 2007, when his 1995 painting Execution sold for £2.9 million ($4 million), the highest price ever fetched by a contemporary Chinese painter at that time. The painting had been bought by investment banker Trevor Simon at an auction house in Hong Kong, on the condition that it wouldn’t be displayed for five years.

For Simon, the work was an essential message. “I realized this stood for everything that was going on at the time,” he told CNN. Simon ponied up two-thirds of his annual salary for it.

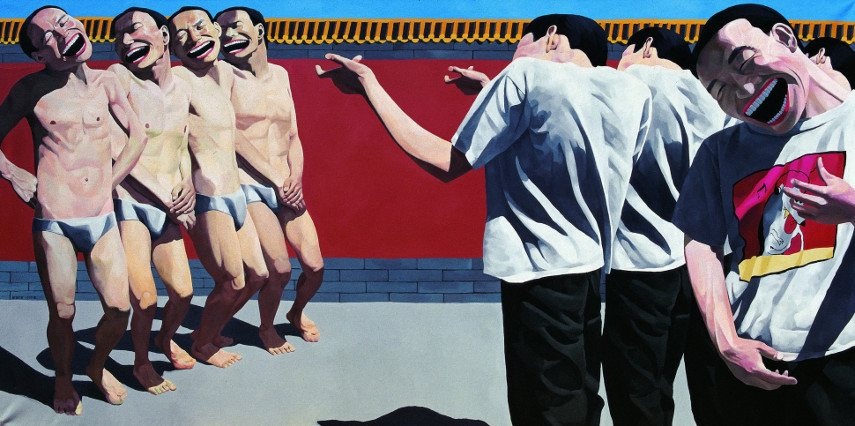

The piece displayed the red and gold walls of Tiananmen Gate, while the positioning of the firing squad nodded to famous images of political martyrdoms from Western art, like Goya’s The Third of May 1808 and Manet’s The Execution of Emperor Maximilian. The guard turning to us has the posture of a soldier in the latter, but wears the clothes of an innocent civilian — perhaps this human doesn’t want to shoot, but the system he’s trapped in gives him no choice. The prisoners are naked, hands bound, to indicate their helplessness. Soldiers and prisoners with identical faces reminds of Jiǎng Yànyǒng’s 蒋彦永 assessment of the massacre’s real tragedy: the victims were “our own people, killed by children of the Chinese people, with weapons given to them by the people.” What else could they do but laugh?

What’s the big joke? To the West, the Smileys are a comment on the political crackdown, but Yue says Tiananmen was just the “catalyst,” the painting describing “the whole world’s human conflict.” But it feels like a commentary on Chinese politics. Laughter was the only means of escape from “helplessness.” Yue told the Huffington Post it indicated “the absence of our rights that society has imposed on us. In short, life. It makes you feel obsolete, which is why, sometimes, you only have laughter as a revolutionary weapon.”

Perhaps it thinly papers over China’s current moral void and lack of meaning? Critic Lì Xiàntíng 栗宪庭 (who coined the term “Cynical Realism”) calls Yue and others “a self-ironic response to the spiritual vacuum and folly of modern-day China.” It certainly taps into China’s culture of hiding true feelings behind a mask of fixed expressions, “giving face.”

Or it may be a positive? Yue has said on Phoenix TV (the show 舍得智慧讲堂 shědé zhìhuì jiǎngtáng) that the smile was to alleviate fears and doubts, created alongside his commune friends to express the positivity of the new era and the joy at finding freedom in the art villages: “The image of laughing is a guarantee to me that everything will be good, just like the promise of the next life in Buddhism. But the reality is not like this, it’s chaotic and weird. I decided to use the image of laughing to remind my circle of people that tomorrow will be better.”

It’s unclear what his arrangement with the authorities is, given the overtly political element of some of his work, but he can’t be all that rebellious if he can host exhibitions with the Tongzhou District Propaganda Department. Perhaps he uses the ambiguity of his work as a means of survival — the laugh optimistic for the Party, a mask for pessimism in the West.

Or perhaps he’s playing a long game. In a Christie’s catalogue from 2007, he discussed the importance of idols: “All I did was to borrow what they do, reproducing myself as an idol over and over.” Duplicating such an image makes it a powerful force, gaining a life of its own — as those who had lived through Mao’s Cult of Personality knew. Does Yue aim to put his face everywhere, reminding of the vapidity of mass media and consumer culture? CNN took his final remark to their interviewer as tongue-in-cheek, but “I want to be famous” may be a more revealing statement than many think.

Since 2007, his work has seeped into all sorts of realms, making light of the crucifixion…

…Lei Feng (so much for not being political)…

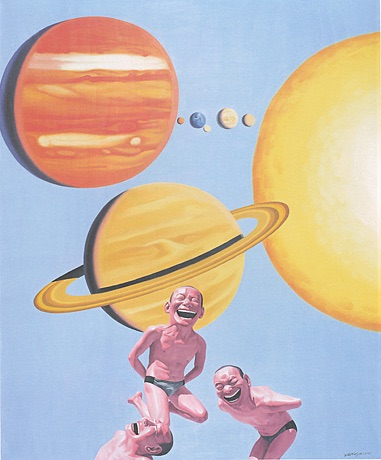

…space…

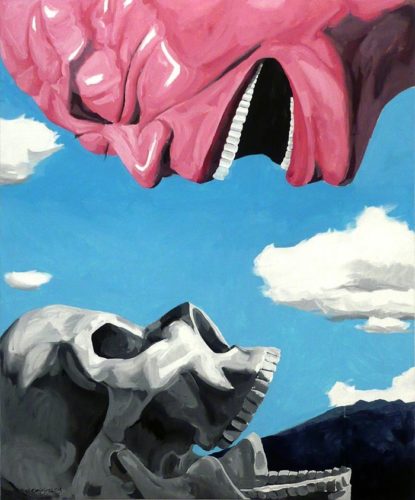

…mortality…

…swans…

But is it now mainly for the money? Yue certainly benefited from the 2008 financial crash, Chinese collectors channeling their funds into artists considered blue chip by Western endorsement. Thanks to his smiling faces, Yue ranks 22nd on the list of “Top 1000 Contemporary Artists at Auction, 2000-2019,” selling $159 million at auction over that period. According to the Financial Times, he’s now based in a big mansion with two full-time assistants, the spoils of many years churning out hundreds of paintings which look great on merchandise. As one Artnet columnist reminds us, whether Yue likes it or not, “the content of his art cannot be separated from its inherent marketability,” especially to a Western audience who see in him their own artistic styles and traditions of political protest. Critics like Susan Moore argue some of the cynical realists pandered to that image of political protest to boost sales.

It was the “export art of the 90s,” agrees a prominent Beijing art dealer. Over the course of a 15-year career in the country, “I haven’t met any Chinese who collect his work.” One Chinese art collector (who lived through the same era, with a penchant for traditional Western-style realism) criticized the “quick” and “unskillful” appearance of Yue’s work, telling me the high market price doesn’t make sense for an artist with little time for detail (witness the peg-like teeth in Yue’s upper jaw, whose numbers ebb and flow between 14 and 22 depending on the canvas).

But Yue agrees here. He told CCTV he believes people only pay attention to his work because of the high price. “Some artists are totally market-driven. Others are so supercilious they don’t want anything to do with it,” he told the Financial Times. “I am somewhere in the middle.”

Meg Maggio, Director of Pékin Fine Arts, has known Yue since the 1990s. “He’s a serious committed artist, always has been,” she says via WeChat. “What is less well known is that he’s mentored young artists who greatly admire his talent & longevity in the artworld.”

Indeed, Yue has been trying to move away from his old oeuvre, but with little success. Although in the late 2010s he started exploring his creative impulses in new directions with mazes and scar portraits, they do not have the same impact as his earlier work. Indeed, it’s a struggle to find images of these two series on either Google or Baidu. But he keeps having to come back to his old work, telling CCTV that he feels “shackled” — “to make money, the market forces you to draw smiling faces.” Today he feels he lacks the youthful energy so precious to his work at the old Summer Palace art commune. He’s trapped by his own face.

It’s a nightmarish scenario captured in one overwhelming canvas where the laughing faces fill the space completely, offering the viewer no escape. If given the opportunity to speak, the faces merely replicate themselves, nothing beyond the façade but an infinite and uniform sea of shrieks:

When it comes to Yue’s career, they have the last laugh.

Chinese Lives is a weekly series.