On the collective loss and preservation of migratory stories.

“We are saving this for you, the future.”

The first time I met Camille Wing was the winter of 2018. She was in her 90s, her back hunched, but her small stature did not dim the fierceness in her eyes. She insisted on climbing up the stairs to show me the Kwan Tai Temple (关帝庙 guāndì miào, officially listed as the Taoist Temple on the National Register of Historic Places). Next to the display table full of incense burners, fortune sticks, moon blocks, and other ritual objects, we chatted for hours.

Camille was the matriarch of China Alley in Hanford, one of the few remaining historic Chinatowns in rural America. The town of Hanford was formed in 1877 when the Southern Pacific Railroad extended into California’s San Joaquin Valley. Many Chinese laborers came to work on the tracks, and later stayed for farming. They were mostly from Sam Yup (三邑 sānyì), the three former counties of Namhoi (南海 nánhǎi), Poonyu (番禺 pānyú) and Shuntak (顺德 shùndé) in Canton — now known as Guǎngdōng 广东 — province. China Alley prospered to include restaurants, homes, boarding houses, general merchandise stores, herb shops, gambling establishments, a Chinese school, and a temple. Over 100 years later, the brick buildings remain largely intact and unaltered.

When Camille started to get involved with the China Alley Preservation Society in the 1970s, she mostly had no idea what she was looking at. She was born to a Caucasian mother who met her father when she was teaching English in San Francisco Chinatown. Because of anti-miscegenation laws in the ’20s, they married in Mexico before returning to live on a ranch in Hanford. Camille did not know much about her parents’ lives, and by the time she was old enough to ask questions, the people with the answers were gone. By the same token, the one thing Camille regretted most was not learning Chinese, and by the time she wanted to learn about the artifacts housed in the temple, she had neither the language nor the people who spoke the language to ask. When the Chinese community started to disperse and move away after World War II, however, Camille and the Wing family never left Hanford. She said to me: “We are saving this for you, the future. If we don’t save things, they will go away with us, and there aren’t many of us left.”

My interest in the history of Chinese in America stems from a backpacking trip in the Klamath-Siskiyou Mountains, where I stumbled upon what locals called the “Chinese wall.” It was a hand-stacked rock wall made of mining tailings, stretching as far as the eye could see. On that same trip, I discovered the Weaverville Joss House, California’s oldest Chinese temple. The caretaker of the temple directed me to China Alley, and I fell in love with the town and the people I met that I now consider family. With a population of around 58,000, Hanford today is a quiet agricultural town, surrounded by acres of almond, walnut, peach trees, among other crops.

The China I grew up in is nothing like any Chinatowns I have been to in the U.S. My family never set up altars at home. The extent to which I know about temples and rituals is limited to the famous Lingyin Temple in my hometown of Hangzhou and some basic customs of worship my family performs when we visit my maternal grandfather’s grave. On the other hand, both my parents are the only ones among their siblings who moved to a big city. With Mandarin being the only language spoken at home and instructed in school, I never learned to speak the dialects from either side of my grandparents, and I often have trouble understanding them. The rapidly modernizing cityscape of China and the destruction of rural villages stands in stark contrast to the slow pace of simultaneous decay and preservation that I witnessed in Hanford. It was both strange and familiar to learn about Chinese traditions and histories that I never knew — in the least expected place.

Like those before me, I was suddenly uprooted from my homeland and displaced to a foreign “land of opportunity.” Yet my journey across the ocean is also completely different, benefiting from China’s recent decades of economic boom to pursue higher education in the U.S. I am reminded of how our individual personhood is entangled in the geopolitical relationship between the two countries and the racial capitalism that the U.S. immigration system is rooted in. Chinese immigrants first came to the U.S. as indentured laborers, yet when they presented a “threat” to their white counterparts, the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed — not dissimilar to the U.S.’s increasingly Sinophobic rhetoric and discriminatory laws against Chinese scholars today.

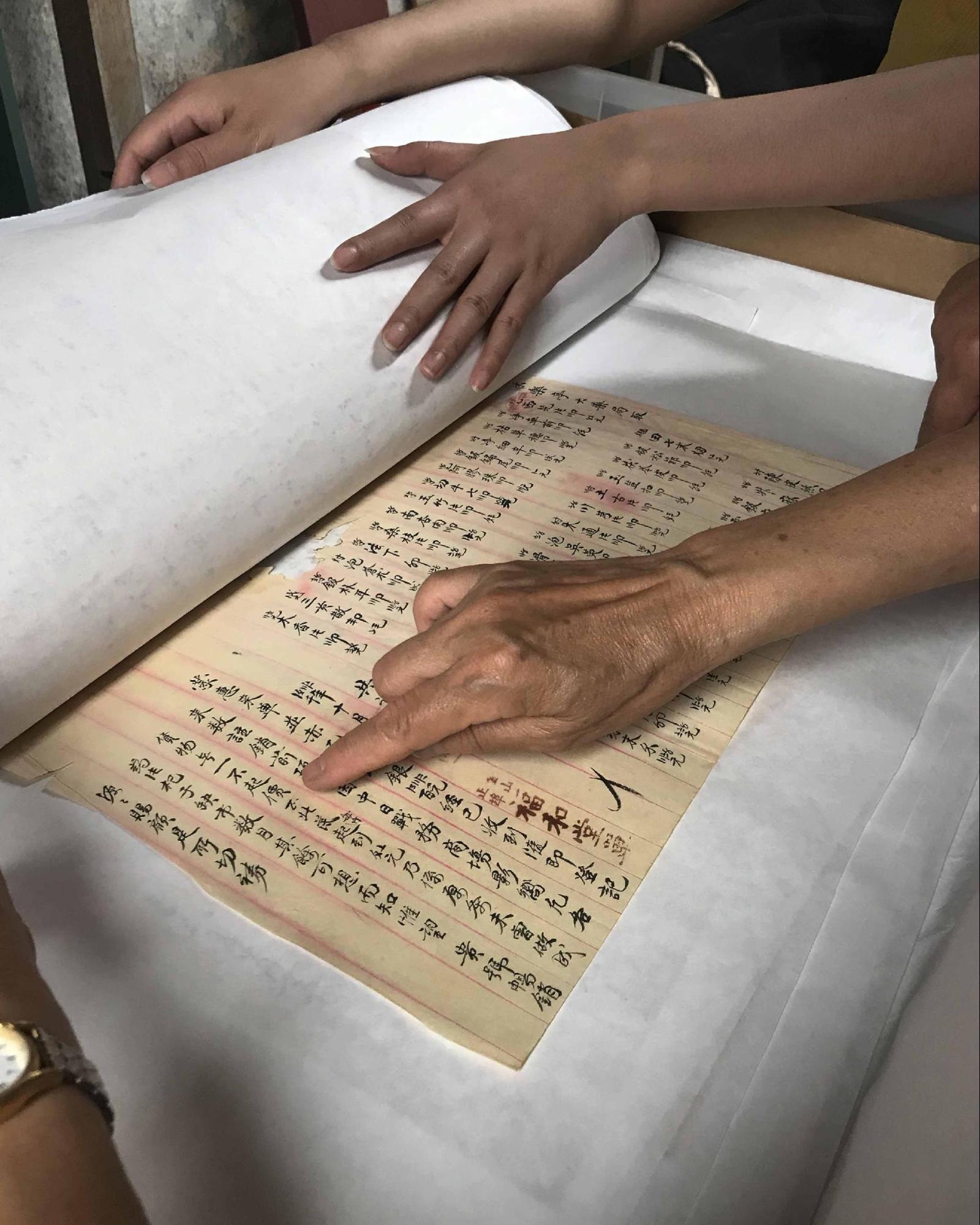

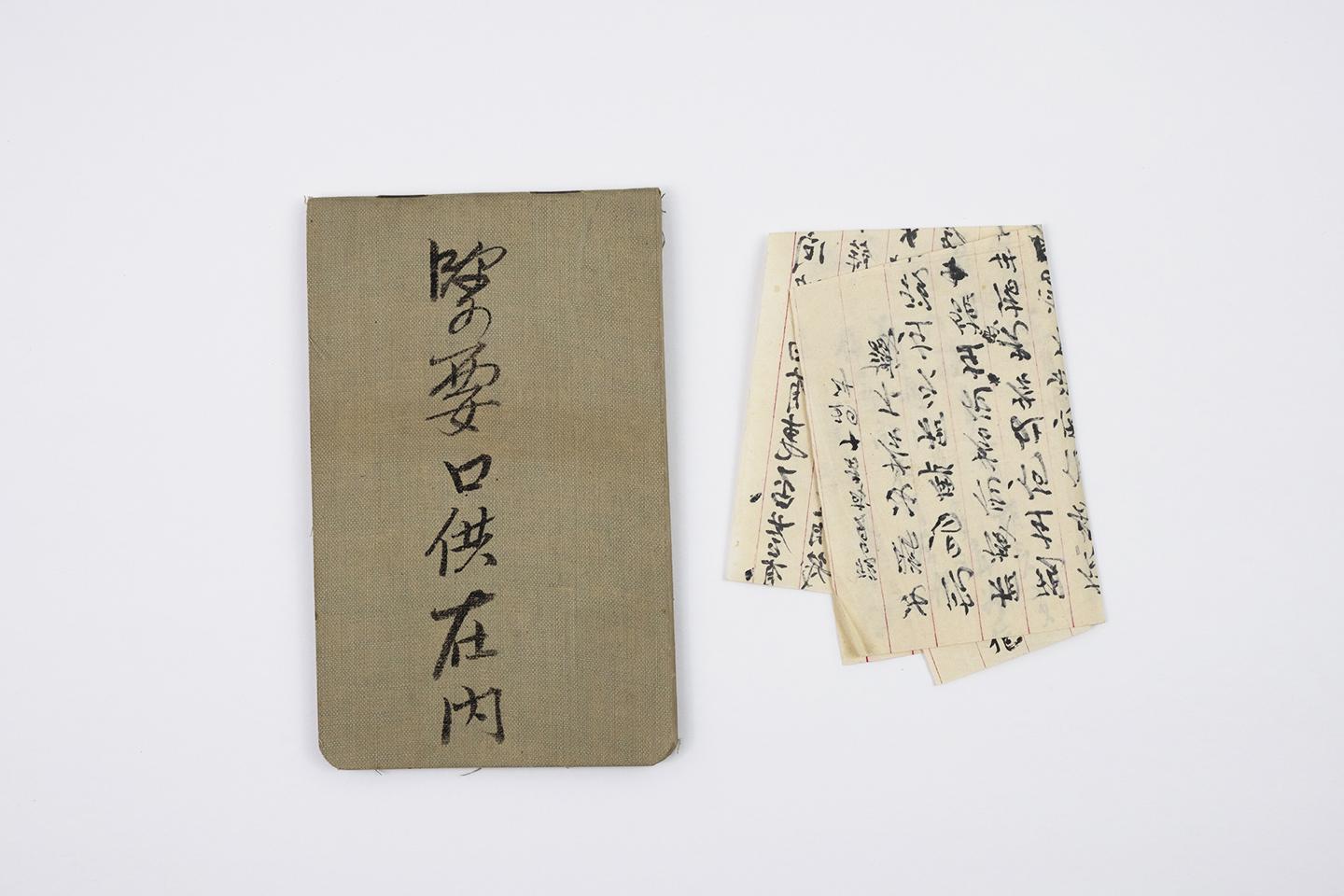

Through digitizing and archiving China Alley’s artifacts and documents, I discovered coaching papers from paper sons and daughters who were detained and interrogated at Angel Island during the Exclusion era. Following the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, which destroyed public birth documents in its subsequent fires, many Chinese laborers claimed that they were born in the U.S. or born to American parents, and used fraudulent documents to enter the country. These coaching papers contain detailed biographical information of the identities that paper sons and daughters memorized, later corroborated by their “paper fathers” before they were allowed in the U.S. As I am currently going through the visa application process, which continues to reduce whole existences into quantifiable data and language legible to the dominant white class, I often think of the names and stories of an entire generation of Chinese immigrants that were lost, as well as the countless family legends they created along the way.

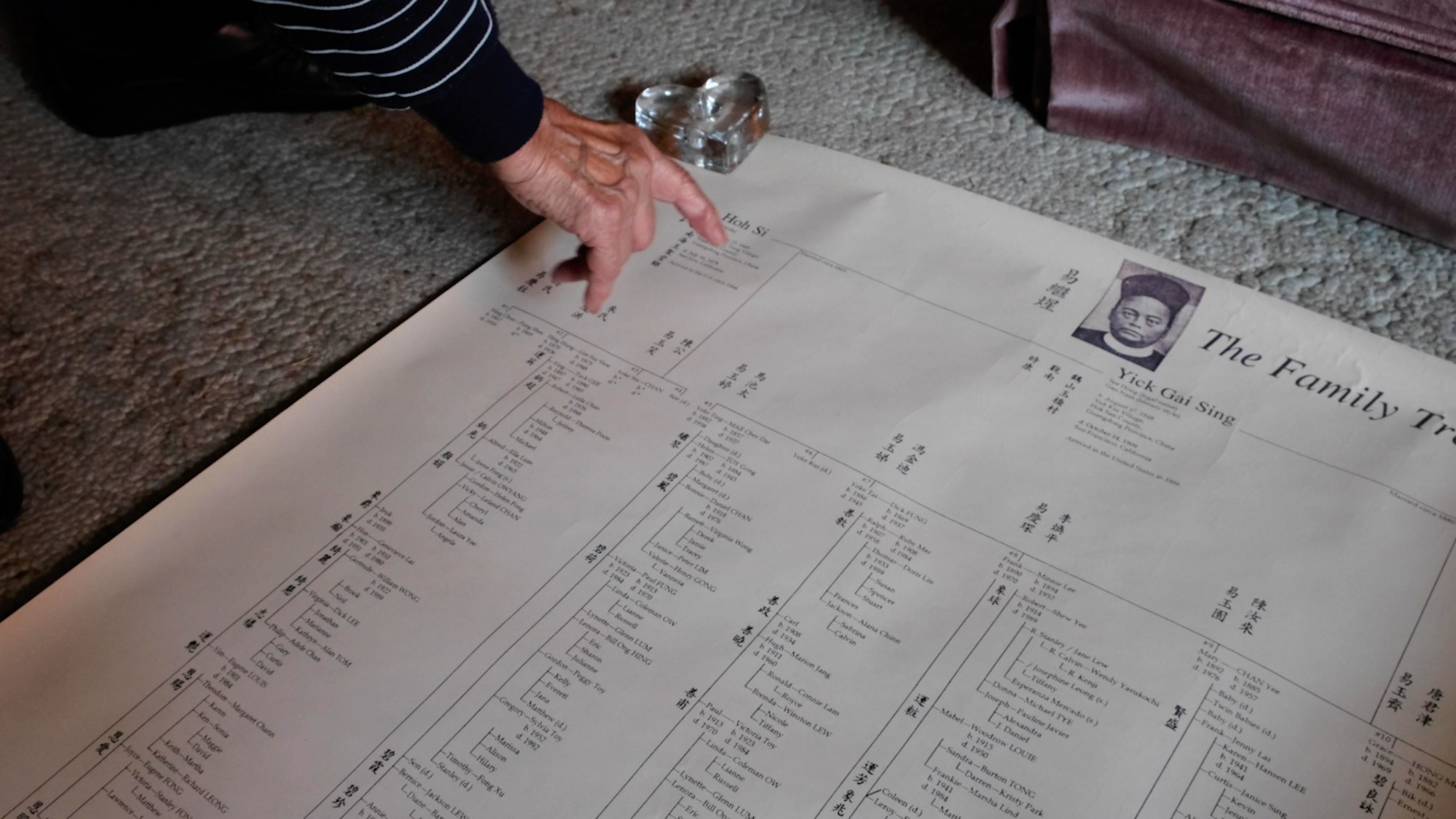

Arianne Wing, Camille’s daughter, writes about her encounters with the spirits of her ancestors, especially her great-grandfather, who jumped into the Pearl River to escape political persecution during the Taiping Rebellion before eventually settling in Hanford. There is a Chinese cemetery in Hanford that I frequent, and although most of the bodies were sent back to China, leaving the cemetery only an altar and a few headstones, I believe our ancestors’ spirits remained and are wondering besides me. With the passing of elders who carried migratory narratives, China Alley as a physical space now holds all their collective memories. For the longest time I thought my presence was transitory, yet the longer I spend in Hanford, the more I realize that I am not just passing through. I am soaked in the blessings and energy from my ancestors; I am also leaving my own trace on this land, in between the peeled walls and the yellow pages of letters, ledgers, and newspapers that I photographed and archived.

I am reluctant to speak only about the violence and discrimination that Chinese people have endured in this country — portraying them as perpetual victims without agency to defend themselves. Gloria Jean Watkin (known by her pen name bell hooks) writes about “marginality as much more than a site of deprivation…that it is also the site of radical possibility, a space of resistance…not just found in words but in habits of being and the way one lives.” It is a space she chooses. (See: Marginality as a Site of Resistance, pages 341 to 343).

I would like to consider paper sons and daughters’ fabrication of identities and the preservation of China Alley both as creativity and power born out of this site of resistance that one chooses, with agency. There exists as much replanting and re-placing as there exists uprooting and displacing. It is how one rises above forced disappearance and active erasure that matters to me. Paper sons and daughters did it through cheating the unfair system, Camille did it through nearly half a century of relearning and preserving, and I am doing it now by continuing Camille’s legacy. In My Old Home, Lǔ Xùn 魯迅 writes, “The Earth had no roads to begin with, but when many people passed one way, a road was made.” I am walking on this dirt road that Camille and others before me trod on.