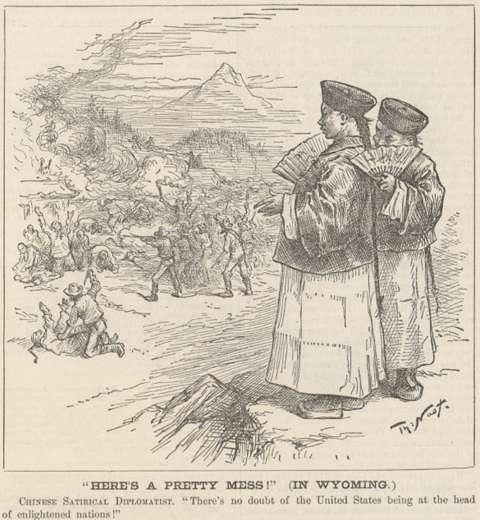

This Week in China’s History: September 2, 1885

In the autumn of 1885, officials of the Qing dynasty made their way from San Francisco and New York City to the Wyoming Territory (five years before it would become a state). What they found there says much about U.S.-China relations in the 19th century — including conventional wisdom about the competence of the Qing dynasty — but also about the trajectory of American history and the shape of U.S.-China relations today.

Tensions had been growing that summer between the white and Chinese communities of the mining town of Rock Springs, Wyoming, where some 600 Chinese and 300 whites mined for coal. Vulnerable and marginalized, Chinese miners often accepted lower wages than their white counterparts, and were used as strike-breakers by mining companies. For their part, some unions expelled Chinese workers — which, in addition to being a failing tactic in the labor dispute, illustrates the ability of racism to trump economic interest. White miners, and nascent labor unions like the Knights of Labor, grew increasingly resentful of the Chinese.

Just three years earlier, the Chinese Exclusion Act effectively ended Chinese immigration to the United States. Driven by racism, xenophobia, and a narrative to portray the United States as a white country, the act blamed many of America’s ills on Chinese immigrants. While the act halted immigration, and would remain in force for 60 years, Chinese communities remained in the U.S., as did the racism that had motivated the laws to begin with.

On the morning of September 2, 1885, those two factors came together when Chinese and white miners fought in the No. 6 coal mine near Rock Springs. A white miner killed a Chinese miner with pickax and severely beat another before a foreman could intervene and disperse the crowd.

This was just the start. By early that afternoon, a mob of about 150 people — mostly white men but some women and children as well — were armed with guns, knives, clubs, and hatchets, and marched toward Chinatown. (By 1885, some 200 communities in the Western United States had significant Chinatowns.) Attacking any Chinese found in the streets, and sometimes pulling people from their homes, the mob ordered all of the city’s Chinese residents to leave. Pursuing those who fled with shotguns until they escaped into the surrounding mountains, the terrorists then laid waste to Rock Springs’s Chinatown.

The next day, a smoking ruin was all that remained. Twenty-eight people — all Chinese — had been killed, and another 15 injured. The entire population of Chinatown — more than 500 people — had fled into the hills, hiding from their attackers and asking for assistance.

Within days, 22 miners were arrested for the murders, but in October a grand jury returned no indictments at all. No individuals were found responsible for the death and destruction in Rock Springs.

To the extent that the Rock Springs Massacre is known, it is most often as part of American history. But this is a column on China’s history, and the episode sheds light on dynamics between Qing China and the United States, as well as insights to the Qing government itself.

After Rock Springs, American “experts” opined that the Qing government would likely let the incident pass without notice, because of Chinese ambivalence toward overseas immigration. Moreover, as an article in the San Francisco Chronicle suggested, “persons who are well posted on international law say that this country can offer the numerous violations of the Immigration Act by subjects of China as a set-off to any damages that China may claim.”

The view from China, though, was very different.

Sometimes missed in the flurry of treaty ports and gunboats that enforced European and American mechanisms of diplomacy on China, the opening of relations between China and the West included the establishment of Qing diplomatic apparatuses abroad. In 1885, the Qing ambassador to the United States was Zheng Yuxuan, who had arrived in the U.S. late in 1881. In contrast to U.S. opinion that China would be unable or uninterested in pursuing this matter, Zheng dispatched two consuls — Huang Shichen from New York and Frederick Bee from San Francisco — to investigate. They arrived in Rock Springs late in September, collecting heartbreaking and stomach-turning testimony from survivors.

In her new book, The Chinese Question, historian Mae Ngai brings together several of the accounts Bee and Huang recorded. Huang, in particular, is sure to name each of the victims and describe their fate in compelling detail. “The dead body of Yii See Yen was found near the creek,” Ngai quotes Huang. “The left temple was shot by a bullet, and the skull broken. The age of the deceased was thirty-six years. He had a mother living at home [in China].”

Bee’s report to the embassy laid out what transpired more generally, but with no less impact. The Chinese of Rock Springs…

were attacked by a large body of armed and unarmed miners, estimated at over one hundred, and brutally shot down, their dwellings surrounded, robbed of everything valuable, then set on fire. Those who attempted to escape from their burning buildings were shot down or driven back into the flames. Fifteen remains of those burned have been taken out, not one of which could be identified. There is not the slightest testimony that the Chinese made any resistance whatever. No appeals for mercy were heeded by these human fiends. “No quarter, but shoot them down,” was the slogan of these murderers during the massacre of these inoffensive and unarmed Chinese miners.

Bee also interviewed the postmaster of Rock Springs, a white resident named O.C. Smith. Smith not only corroborated other accounts of what had happened, but he adds a layer to the anti-foreignism of the mob in his description: “There was a complete reign of terror here during the next day. Toward the close of this day, September 3, there were rumors that the Mormons were to be driven out of town that night, and the people were greatly excited; but that night passed and nothing was done.”

Ambassador Zheng collated these reports and lodged a formal protest to Secretary of State Francis Bayard. Submitted on November 30, Ambassador Zheng detailed the murder and terrorism committed against the Chinese community of Rock Springs and demanded justice. “It therefore remains for me to ask, in the name of the Emperor and Government of China, that the persons who have been guilty of this murder, robbery, and arson, be brought to punishment; that the Chinese subjects be fully indemnified for all the losses and injuries they have sustained by this lawlessness; and that suitable measures be adopted to protect the Chinese residents of Wyoming Territory and elsewhere in the United States from similar attacks.”

It took some months for a response from the American government. When it came, it was both refreshingly frank and maddeningly legalistic.

Of the September 2 massacre, Bayard wrote, “Race prejudice is the chief factor in originating these disturbances, and it exists in a large part of our domain, jeopardizing our domestic peace and the good relationship we strive to maintain with China.” Bayard went on to express his outrage at what had happened. “Let me assure you, however, that I but speak the voice of honest and true American citizens throughout this country, and of the Government, founded on their will, when I denounce with feeling and indignation the bloody outrages and shocking wrongs which were there inflicted upon a body of your countrymen. There is nothing to extenuate such offenses against humanity and law….”

And yet.

Bayard rejected the Qing claim that this had been an international incident. Unlike 1850 riots in New Orleans and Key West, when Spanish royal insignia had been desecrated, the Rock Springs rioters had attacked individuals, not nations. And while the individuals involved had suffered terribly and wrongly, Bayard blamed the victims: “The peculiar characteristics and habits of the Chinese immigrants have induced them to segregate themselves from the rest of the residents and citizens of the United States, and to refuse to mingle with the mass of population as do the members of other nationalities. Chinese laborers voluntarily carry this principle of isolation and segregation into remote regions where law and authority are well known to be feeblest.” In other words, the Chinese isolate themselves, refuse to integrate, and work in remote regions where the protection of law is weak. The laborers had put themselves in harm’s way, and therefore the American government could not be held liable when harm came.

While rejecting the American government’s responsibility, Bayard reversed course once more by invoking mercy. Compensation might be possible “not as under obligation of treaty or principle of international law, but solely from a sentiment of generosity and pity to an innocent and unfortunate body of men, subjects of a friendly power, who, being peaceably employed within our jurisdiction, were so shockingly outraged.” Bayard recommended to Congress that compensation be provided on that basis.

In April 1886, Ambassador Zheng received a check from the U.S. government for $174,000 (about $4.6 million in today’s terms), an amount a little greater than the property damage the Qing investigators had assessed in their reporting. It was hoped that this compensation would, in the words of Secretary of State Bayard, “confirm and perpetuate the friendship and comity which, I trust, may long exist between our respective countries.”

This Week in China’s History is a weekly column.