This Week in China’s History: September 6, 1899

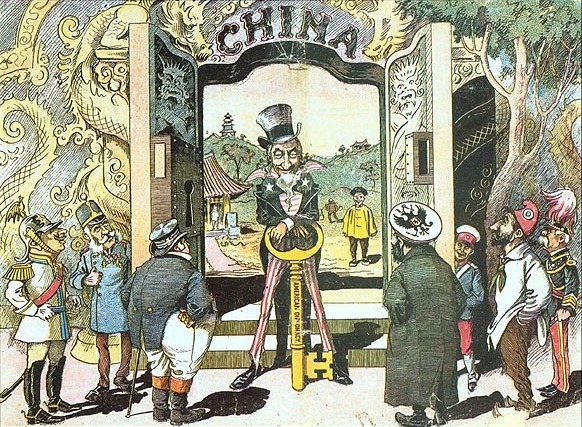

Last week’s column dealt very directly with China-U.S. relations in the late-19th century, and this week continues that trend (preview of coming attractions: next week will again focus on the United States and China, though about a century later). This Week in China’s History looks back at U.S. Secretary of State John Hay’s 1899 “Open Door Note” that purported to support China’s sovereignty and the principles of free trade, but arguably did just the opposite.

It’s a cliche among historians to define particular decades — almost any decade, if we’re given the chance — as “pivotal.” With that in mind, I’d still argue that the importance of the 1890s for China’s foreign relations is hard to overstate. The Qing empire entered the decade with hopes that the self-strengthening program reinvigorated after an 1884 defeat by France was finally bearing fruit. The 1894 war with Japan ended any illusions about that: China was unable to defend its territorial interests. The rest of the decade was the “carving of the melon,” to use the parlance of the day, as Britain, France, Germany, Russia, and Japan divided the ailing dynasty.

The process had actually begun decades earlier. The Opium Wars spawned a British colony at Hong Kong and a handful of semi-colonial “treaty ports,” which grew in number and autonomy over the course of the century. The 1858 Treaty of Aigun ceded more than 230,000 square miles of Manchuria to Russia. But it was in the 1890s that China seemed truly in peril.

The spark to the fuse on China’s partition was not lit by Europeans, but by Japan. The terms of the 1894-95 war gave Japan the Liaodong Peninsula, jutting south from Manchuria toward Shandong. The Japanese claim was soon renounced thanks to international pressure — the Europeans, it would seem, did not appreciate the Japanese usurping their colonial prerogative — yet the move suggested that the informal imperialism that had guided much of European policy toward China might need to be reconsidered. Might it be time to divide China, formally, among the European powers?

Europeans were practiced in this sort of thing. In 1884, they gathered in Berlin to impose their map and their ambitions on Africa. The conference assigned virtually the entire continent to a European occupier to colonize, exploit, and conquer as it saw fit.

Germany, late to the game of imperialism, hosted the 1884-85 conference, and in China, too, it was at the forefront of colonial expansion. In 1897, German marines landed at Jiaozhou Bay, in Shandong, using the murder of two German priests as a casus belli, and occupied the region. Within months, they had sealed a 99-year lease on the territory, centered on the port of Qingdao. Britain countered with two similar arrangements of its own: 99-year leases on the New Territories of Hong Kong, greatly expanding the borders of that territory, and also at Weihaiwei on the north coast of Shandong. The race was on.

Britain also obtained a sphere of influence in the Yangtze River valley, gaining privileges and rights in a dozen provinces. France secured influence in southwest China, neighboring its colony in Indochina. Russia pushed its railway across the territory of Heilongjiang and Jilin, establishing an effective colony in Harbin in 1898 and economic preeminence across Manchuria. Japan gained special privileges in Fujian. Even Italy, latest of all to the frenzy, sought a sphere of influence (in Zhejiang, though this request the Qing was able to refuse).

While France, Britain, Russia, Japan, and Germany expanded their presence, there was one other colonial power not represented: the United States. Its recently ended war with Spain had left the U.S. not only with Caribbean colonies like Cuba and Puerto Rico, but an Asian colony too: the Philippines.

Newly the world’s largest economy and a colonial power, a presence in China was on the minds of American policymakers. American merchants and diplomats played important roles in ports like Shanghai — where there had briefly been an American Concession before it joined its British counterpart in forming an “International Concession” — but there was not a part of China that was American.

Not only that, but where would America plant its flag if it could? The British, French, Japanese, German, and Russian spheres of influence covered nearly the entire coast. There was no realistic place where an American colony could be established, not when their European and Japanese rivals had such a head start.

Of even greater concern was not the prospects for an American colony, but the status of treaty ports like Shanghai. Historian Isabella Jackson, in her book Shaping Modern Shanghai, devises the concept of “transnational colonialism” to explain what was going on in that — and other — treaty ports. With so many competing powers, no single power could enforce its will just as it pleased. The result was a more cosmopolitan city where multiple colonial powers could take part.

The trend toward direct colonial control, rather than multilateral treaty ports, threatened this arrangement. If Britain, for instance, took sole control of Shanghai, other countries’ merchants would be at a disadvantage. For Americans, this was especially risky: without a colony to call their own, they would potentially be shut out of the market.

With this in mind, John Hay issued a statement on September 6, 1899, asking the governments of the other powers active in China — Britain, Germany, France, Italy, Japan, and Russia — to guarantee equal and open access to Chinese ports. Rather than partitioning China into colonies, Hay in effect asked that China be a free trade zone, with equal tariffs applying to all countries, tariffs that would be collected by the Qing state. This first of three “Open Door Notes” was received by each country in the same way: agreeing to abide by these terms if the other countries would agree as well. Although this was an evasive and noncommittal response, Hay took from it what he wanted, announcing later that fall that all countries had accepted the principles of the open door.

The Office of the Historian at the U.S. State Department suggests that the Open Door Notes “contributed to the idea of a Sino-American ‘special relationship’” by supporting Chinese sovereignty against European colonialism. While the Europeans and the Japanese sought to claim pieces of the Qing for themselves, America defended China’s integrity by resisting those claims.

It was not necessarily seen that way in China, however.

The Boxer Uprising, which emerged even as the Open Door Notes were being issued, was certainly not the result of Hay’s policies or proposals, but the U.S.’s self-centered intervention in China’s foreign policies contributed to the xenophobia that drove the Boxers.

A year ago in The China Project, David Volodzko wrote about the Boxer Uprising and its role in the anti-Asian racism in the West. Images of “barbaric” and “superstitious” Boxers murdering Western missionaries moved from newspapers to the Western imagination, encouraging the idea of a “yellow horde” that has persisted.

While the actions, and perceptions, of the Boxers fueled anti-Asian sentiment in the West, the Boxer Protocols, which harshly punished the Qing government and the Chinese people, did the same to drive suspicion of the West in China. (Signed on September 7, 1901, they were another possible choice for This Week in China’s History.) This much is well established, but I would argue that Hay’s Open Door Notes needs to be seen as part of this process as well. The American policy was, at best, paternalistic and stripped China of its rights to negotiate treaties or relationships of its own accord. Hay proposed that the door be left open for all to enter, but the door was not to his house!

Almost everything about China and its relationship to the United States has changed since 1899. Rather than a johnny-come-lately imperial power, the United States is the global superpower. China is not a politically weak potential market, but a power in its own right and the world’s largest trading nation. Yet the attitudes that shaped the Open Door Notes remain visible in the ways the two nations view one another: China bristling at affronts to its sovereignty, America imagining itself as able to transcend the rivalries and arrangements of other nations.

Perhaps most simply, the two sides’ different views of “free trade” may be what transfers most clearly from 1899 to 2021. It is not lost on the Chinese side that just a decade after the Open Door Notes pledged to support China’s sovereignty, the Qing dynasty collapsed and soon fragmented. As the two sides wrestle over a complex and immense global trading regime, the same issues — free trade and sovereignty — that defined the Open Door era remain front and center in the U.S.-China relationship today.

This Week in China’s History is a weekly column.

China news, weekly.

Sign up for The China Project’s weekly newsletter, our free roundup of the most important China stories.