This Week in China’s History: October 28, 1728

The city of Xi’an has a long imperial past. It was by some measures China’s greatest imperial capital when it went by the name Chang’an during the Tang dynasty. Today, the city is home to some of China’s greatest historical treasures, including a nearly intact city wall, and collections of imperial relics. Nearby, imperial tombs from the Tang — and the terracotta army of the first emperor — underscore that this has been a center of power for a long, long time.

The weight of this past might have made a letter, thrust into the hands of a regional official, a little heavier. Yuè Zhōngqí 岳鍾琪, governor-general of Shaanxi and Gansu, was returning from an official reception to his office when a stranger approached and presented him with an elaborate, but unofficial, letter, signed with the apparent pseudonym “Summer Calm.” Reading the letter later, in private, Yue found that he was being invited to join a plot to overthrow the emperor and the entire Qing dynasty.

The story of Yue Zhongqi and the treason plot is told masterfully in Treason by the Book, by Jonathan Spence. Twenty years after its publication, the book is both a compelling read, proceeding along like a thriller, and rigorous history. Spoiler alert for the paragraphs that follow.

At the heart of the letter General Yue received are the grievances of an occupied land. It is often taken for granted, but ought not be, that China was ruled by a foreign dynasty, and in 1728 the Manchu Qing had sat on the throne in Beijing for less than a century. “Summer Calm” did not mince words: “When the rulers of the Ming lost their virtuous ways, the land of China was submerged and barbarians took advantage of our weakness to enter and usurped our precious throne.”

“Seize the chance to rise in revolt,” the writer urged Yue Zhongqi, “and avenge the fates of the Song and Ming.”

The plotters had reason to think that Yue Zhongqi might be a receptive audience. He was descended from a famous general — perhaps the most famous general of all, Yuè Fēi 岳飞, who had made his name defending China from invasion and standing up against treachery. Summer Calm asserted that since Yue Fei’s beloved Song dynasty, little had gone right for China. Its people had been weak or misguided. Only one exception — a scholar referred to as “the Master of the Eastern Sea” — had tried to uphold the values that Yue Fei had sacrificed for. Would Yue Zhongqi take up his ancestor’s mantle?

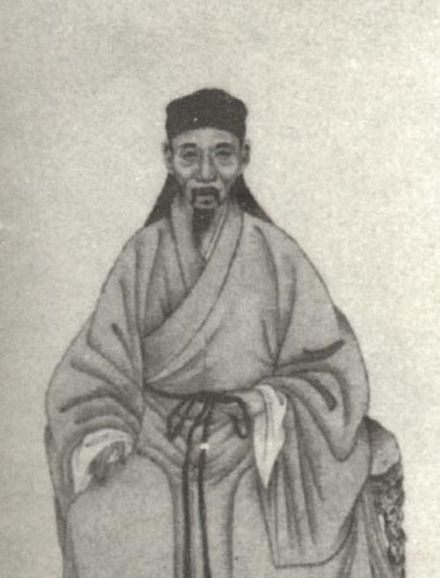

But the younger Yue did not take up arms against the emperor. Instead, he had the messenger arrested, immediately dispatched express couriers to the capital with news of the plot and his prisoner, and began to investigate. Although torture was threatened, gentler means were used to learn that the conspiracy against the Qing was orchestrated by a Hunanese scholar named Zēng Jìng 曾靜. Additionally, Yue learned that the moral paragon known as “Master of the Eastern Sea” was actually a Ming scholar named Lǚ Liúliáng 呂留良.

No ruler tolerates sedition, but the Yongzheng Emperor, who saw threats even where none existed, was vigilant to the point of paranoia. He had come to power under a shroud of suspicion — his father Kangxi had been one of China’s greatest emperors but had failed to arrange for an orderly succession. The eventual Yongzheng Emperor had not been the first choice as heir, and Kangxi guarded his will carefully. When Yongzheng ascended the throne, many of his brothers and their allies rejected the new emperor’s legitimacy. Yongzheng used murder, imprisonment, or exile, adding to the resentment of his reign and, in turn, heightening his paranoia. In Spence’s description, Zeng Jing had “nothing but disgust” for Yongzheng, who “has murdered several of his brothers…plotted against his parents; he persecutes his loyal ministers, and gives his ear only to sycophants; he is greedy for material gain….ever eager to kill others, often drinks himself into oblivion, and cannot control his sexual passions.”

Not surprisingly, when news of a plot against him reached the Forbidden City, Yongzheng acted quickly. Troops were dispatched in December to Hunan, where Zeng Jing and his family were taken into custody. For four months, Zeng was questioned in Changsha, where he detailed his path to sedition, confessing his opposition to the Manchu dynasty, his hopes for insurrection, and his personal antipathy to the emperor. Eventually, he was taken to Beijing for further questioning.

Zeng Jing’s fate was sealed. In November, the bureaucracy — instructed by the emperor to review the case one last time — issued a unanimous opinion: “Lingering execution by slicing for the traitor himself, with summary execution by beheading or strangulation for all his close male relatives aged 16 or over, and exile and enslavement for all the women and minor males in the criminal’s family. All the traitor’s property is forfeit to the state.”

Spence quotes the official recommendation: “With regard to Zeng Jing, we humbly request the emperor to allow us to implement these punishments promptly and sternly, so as to maintain the clarity of the law of the land, and to gladden the people’s hearts.”

(I said there would be spoilers…here is a second warning if you’re inspired to go read Treason by the Book!)

Yongzheng doesn’t follow his officials’ recommendation to execute Zeng Jing. With the plot uncovered, the emperor worries about his legitimacy more than he does his place on the throne. With this in mind, he determines that Zeng Jing would be more dangerous as a martyr than as a would-be rebel. And moreover, Zeng has changed his tune while in prison. Repenting his disloyalty, Zeng Jing writes what amounts to a public confession, a 27-page essay titled My Return to the Good, which explains why he has come to learn that it is not only possible, but to be expected that people from beyond China’s traditional borders — i.e., Manchus — could be Confucian moral exemplars. Far from being barbarians or aliens, “the current empire of the Qing,” he wrote, was responsible for “a rebirth of the virtuous days of the ancient sage rulers.”

Zeng Jing’s essay became part of a longer text, with contributions from the emperor and leading scholars, that described Zeng Jing’s errors and how he had corrected them. This book, A Record of How True Virtue Led to an Awakening From Delusion, was printed and distributed throughout the empire, first at court, then to the top officials in each province, and finally to every school in the realm. As the emperor prescribed in his foreword, “one copy is to be deposited in every local school…. Should I later discover that there is anyone who has not read this book…then the full weight of punishment will fall on the educational commissioners of the provinces concerned.”

Central to Zeng Jing’s confession was that he had been led astray by the writings of Lü Liuliang, the Ming scholar who had denigrated the Manchu dynasty and those who served it. So, while Zeng Jing was exonerated — and became a tool of the Yongzheng Emperor’s propaganda — Lü endured the punishment of a traitor. Though he had been dead for nearly 50 years, Lü was exhumed and his corpse mutilated. His son, also an accomplished scholar, had died two years before; he too was exhumed and his body punished. Lü’s writings were banned, his extended family exiled or enslaved.

Part of Yongzheng’s justification for pardoning Zeng Jing but punishing Lü Liuliang is that Zeng attacked only the emperor himself, while Lü had impugned his ancestors. So while it was Yongzheng’s prerogative to be merciful to the younger man, the crimes of Lü were beyond redemption.

The story’s postscript plays on this same principle. When Yongzheng’s son — the Qianlong Emperor — came to the throne, he revisited the case. Avenging his father, he had Zeng Jing arrested and executed.

Zeng did not suffer alone. Zhang Xi, who had delivered the letter on October 28, 1728, urging rebellion, was also arrested. And so it was, some eight years after spotting Yue Zhongqi near the Xi’an drum tower, Zhang Xi, like Zeng Jing, was slowly sliced to death on a cold Beijing morning.

This Week in China’s History is a weekly column.