Li Gui’s diary: A 19th-century Chinese account of the West

“There are a number of brothels as well, whose guests are greeted with smiles of welcome, some even soliciting their customers right out on the street.”

This Week in China’s History: November 1876

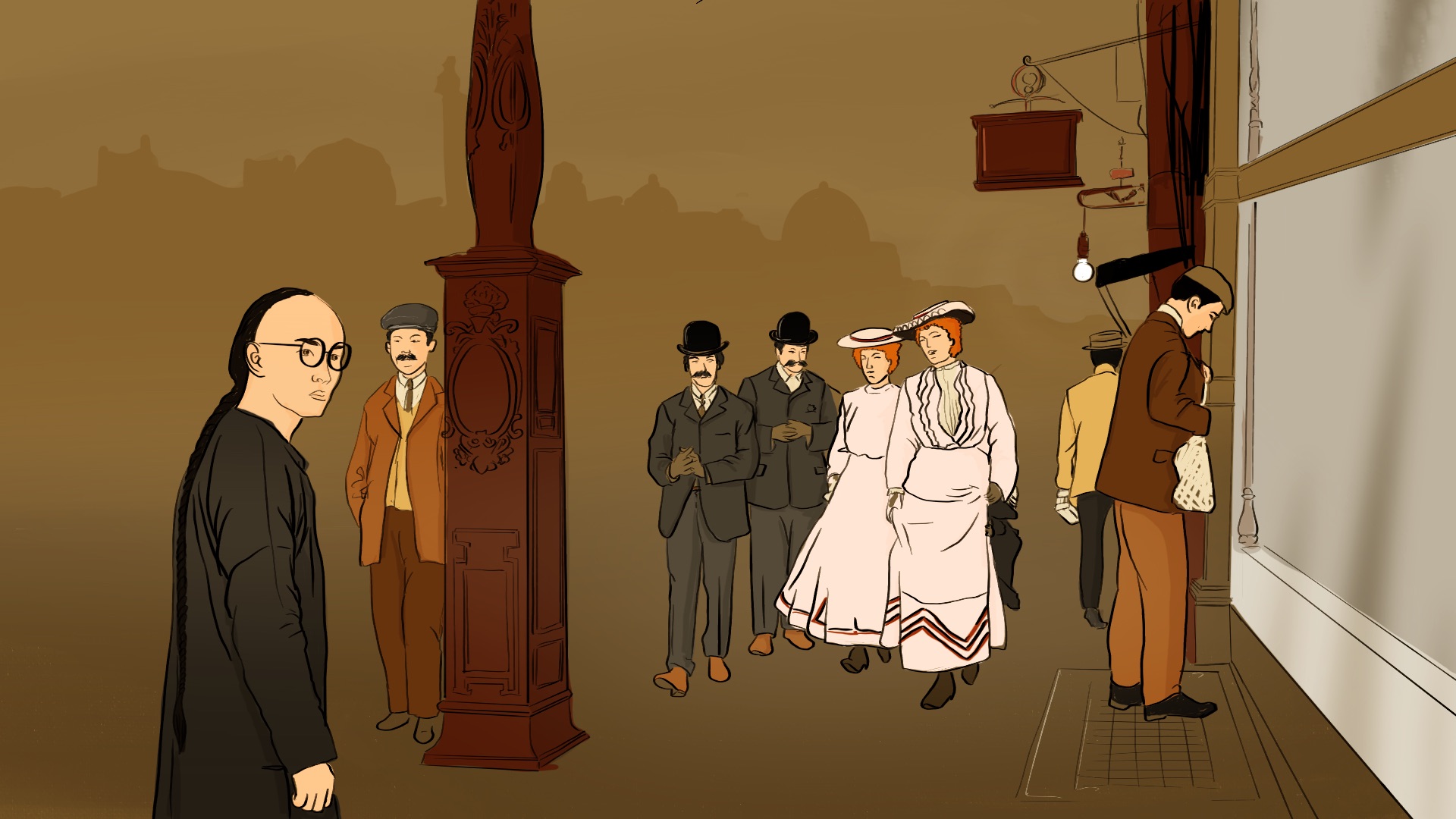

“London,” wrote Lǐ Guī 李圭 in November of 1876, “is the capital city of England and the great metropolis of the West. Its special reputation is indeed well-deserved.”

Li Gui’s account of London was part of his trip around the world, part of a remarkable journey. He kept a detailed diary, translated and contextualized by Charles Desnoyers at Philadelphia’s La Salle University in his book A Journey to the East. Not coincidental to Desnoyers’s interest, Philadelphia was Li Gui’s destination: strictly speaking, the best hook for Li Gui’s travels would be the American centennial exposition at Philadelphia. The Philadelphia fair was a spectacle, and attracted missions from around the world, including the Qing empire. I’ll find another occasion to write about that, but I’m using Li’s time in London partly because it centers on the mundane and everyday, and gives a good chance to think about travelers, translators, and how we know what we (think we) know, especially in a world where we are relying increasingly on others to bring us information that we can no longer get ourselves.

Li was representing the Qing government to the Centennial exposition, but he was, in Desnoyers’s description, “the last of the roving ‘amateur’ diarists…. Unencumbered by diplomatic protocol or official responsibilities, intensely interested in everything around him, by turns frankly impressed and impressively frank about what he sees.”

Desnoyers goes further, asserting that Li Gui’s diary is “perhaps the most insightful and entertaining nineteenth-century Chinese account of the world.” And it is as a diarist that Li Gui is most fascinating. Arriving in London, late in November of 1876, Li has already spent half a year abroad, much of that time traveling across and around the United States, visiting San Francisco, Philadelphia, Washington, New York, and Hartford. Despite his time in the U.S., he does not flatten the differences between England and America, describing the two countries as “altogether different.” Whereas in America, “nothing there has not been recently constructed, [in London] things have more of a feel of antiquity, like an old aristocratic family whose vigor is yet undiminished.”

Li’s description of the English capital is, on the whole, familiar to readers of guidebooks and travel sections. St Paul’s Cathedral, the Houses of Parliament, the British Museum, Hyde Park, Buckingham Palace…he describes all of these with a helpful mix of statistics and impressions. He comments on the “famous people, ancient and modern, honored in bronze and stone statues.” Smaller tidbits, like banks being clustered in “The City,” check out as well. He traveled to the east of London to Woolwich, where he wrote extensively about the British munitions industry, being particularly taken by shipbuilding, torpedo design, and rifle manufacture.

Not all details are right, of course. He may be forgiven for telling readers that “the English state is composed of three islands, one called ‘England,’ another called ‘Scotland,’ and a third called ‘Ireland.’” Also understandable are the kinds of exoticization that often characterize travel accounts. Li declares that London is protected by 5,000 soldiers, wearing red coats and blue pants, with enormous fur hats, a description that while technically plausible, certainly conveys a sense of the city that would have been unfamiliar to most Londoners. And just as many Western accounts of China dwelled on the sexual deviance to be found there, Li asserted that prostitution was as big a feature of “The City” as its financial centers: “There are a number of brothels as well, whose guests are greeted with smiles of welcome, some even soliciting their customers right out on the street.”

Li’s factual errors, exoticization, and biases illustrate one peril of relying on eyewitness accounts. This column has more often focused on Westerns who have gone to China, and the reliability of those sources needs always to be kept in question. How did Matteo Ricci’s desire for converts shape his impressions? What did Norman Bethune’s politics lead him to see in the Chinese Communist Party? And what of the racism of Shanghailanders, or opium traders, or imperial soldiers?

None of these sources is objective because, in part, no such source exists. Bias is present in everything people write, but that rarely means what it has come to mean in today’s rhetoric. A biased source is not usually telling lies, in the sense that it is trying to convince a reader of something the author knows not to be true. Li Gui wasn’t lying when he said Scotland was an island, nor was he trying to overstate the prominence of prostitution in London. Controlling for bias is about understanding the opportunities, motives, and preconceptions of an author, not about proving them wrong.

Controlling for biases is difficult, and important, but whatever biases and errors he brought, Li Gui provides for a Chinese audience a firsthand account of London, other European cities, and the United States.

By the start of the 21st century, firsthand accounts were far easier to come by than they were 100 years before. Airline tickets, travel documents, and accommodations were becoming cheaper and easier than ever. Li Gui was one of just a few Chinese who traveled to London in the 19th century; by 2018, that number exceeded half a million. The numbers were even greater going the other way: more than 3 million Americans visited China in 2017. And while the skewed view of China produced by short visits to Beijing and Shanghai, or the tissue-thin “analyses” based on chatting up a Beijing cabbie, are mockable, the opportunities for understanding grew as mutual exchange did the same.

The last few years, though, have seen these opportunities diminish, and the prospects for the future look dim. The COVID-19 pandemic closed the doors, shutting off virtually all international air travel. Student exchanges, business trips, academic conferences, leisure travel, even most diplomatic visits…all of the ways that China and (to use the example of Li Gui) Europe or North America understood one another ground to a halt.

COVID remains a potent obstacle. Travel to China requires lengthy quarantines, and entry requirements to every country are strict and often changing. But even though it has lasted longer than almost anyone expected, the pandemic will end. When that happens, will travel resume?

A recent analysis by CNN’s Nectar Gan worries perhaps not. “For nearly two years,” she writes, “most people in China have been unable to travel overseas, due to the country’s stringent border restrictions…Chinese authorities have ceased issuing or renewing passports for all but essential travel. Foreign visitors, from tourists to students, are largely banned from China.” And she quotes experts like Fordham law professor Carl Minzner who have been documenting China’s turn inward that has accelerated under Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 (though it had begun before Xi’s rise). Gan quotes UC-San Diego scholar Victor Shih as observing that “other political parties, or even maybe Xi’s predecessors, might have seen this dramatic reduction in contact between China and the rest of the world as a big problem. But for now, the Xi administration does not seem to recognize this as a problem.”

Which brings us back to Li Gui. When he returned to China in early 1877, he shared his impressions and admiration for many Western institutions. He was instrumental in revising the Chinese postal system along European models, and his experience with American trains and the London Underground made him enthusiastic about these technologies. He uncritically accepts the extent of democracy in many Western countries, but writes with passion about certain habits that he sees as a model for China’s self-strengthening: “[Westerners’] understanding of things and unwillingness to cling to stale opinions comes from long experience and practice, broad learning, and especially from reading useful books.”

However naive Li Gui might have been, either in his uncritical acceptance of Western virtues or his exoticization of their vices, he presents a firsthand account, one that could invite comparison, encourage dialogue, and perhaps inspire future visitors. In many ways, Li Gui’s spirit was one that could be seen in the robust exchanges of the 1990s through the advent of COVID-19. If Li Gui set a path for Chinese to travel abroad, though, I fear that few may be able to follow it for some time to come.

This Week in China’s History is a weekly column.