This Week in China’s History: November 28, 1929

Late November in Harbin is the start of winter. Days are usually bright and sunny, but at night the chill that will grip the region for the next six months is already starting to be felt. In 1929, workers in the city warded off the chill with a sense of celebration.

I’ve written before about Harbin — a basketball game, specifically, and the ensuing riot — and the complex modern history of the PRC’s northernmost major city. In 1926, the aforementioned basketball game illustrated the nationalist tensions that defined the city at a crossroads of empire. In the 1920s, Harbin was not even three decades old, and for most of that time it had been run virtually as a Russian colony. It looked the part as well, with cobblestoned streets and art nouveau architecture. Religious symbols and iconography were also abundant, among the most important marks of colonialism. Christian churches — Russian Orthodox, Roman Catholic, and Protestant — were concentrated in the center of town.

After the Russian Revolution, when Chinese authorities took over Harbin’s administration, the city’s environment took on higher stakes. The Buddhist monk Tanxu, whom I introduced in an earlier column, lamented the city’s appearance when he arrived in 1920, tasked with building Harbin’s first Buddhist temple: “Every official or worker who believed in Roman Catholicism, or Protestantism, had built in Harbin three or four large churches, all of which were funded by the Chinese Eastern Railway…. For Harbin, as a Chinese place, to not have a single proper Chinese temple, was in the eyes of international observers very embarrassing…it was simply too depressing to bear!”

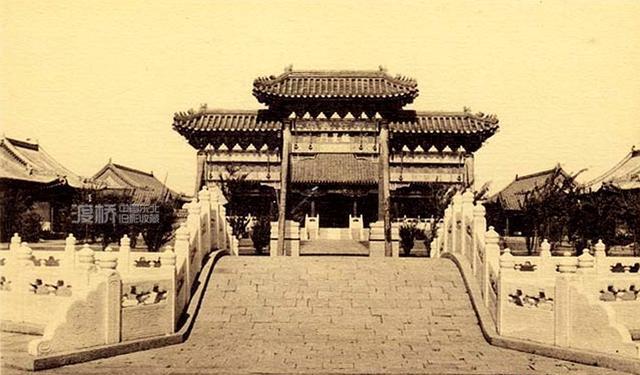

It was General Zhū Qìnglán 朱庆澜 who ordered the construction of a Buddhist temple, which would become Tanxu’s Paradise Temple (极乐寺 Jílèsì). In 1926, Zhu’s successor as Harbin’s top Chinese authority, Zhāng Huànxiāng 张焕相, followed the same template for defining the city as Chinese, ordering the construction of a Confucian temple.

The location of both temples was symbolic and intentional. The city was laid out by its Russian planners as a cross: at the center was the Russian Cathedral of Saint Nicholas (a wooden structure built in the 1890s that burned during the Cultural Revolution). At the base of the cross, connected by a wide avenue leading down from the cathedral, was a Russian cemetery. Chinese temples were built literally overshadowing the Russians’ graveyard. In 1900, a funeral procession from the cathedral would pass along a European-style road lined with Christian churches and some Western-designed buildings. After 1926, the distinctive silhouette of a pagoda and the gleaming yellow roof tiles of the Paradise Temple stood in front of the cemetery entrance.

The cornerstone of General Zhang’s Confucian Temple was dedicated on National Day — October 10 — 1926. Zhang gave a brief speech explaining the day’s significance, and followed with a full-blown nationalist spectacle. According to newspaper reports, thousands of Chinese students in uniform marched from the temple to the Russian cathedral, about a mile away. There, brass bands, flags, garlands, and speeches announced that whatever Harbin’s past had been, its future was Chinese.

The construction of a Confucian temple at that moment was an oddity in China. In many places — Suzhou perhaps most famously — Confucian temples and Confucian practices represented an old — and old-fashioned — way of doing things. As historian Peter Carroll explained in his book Between Heaven and Modernity, at exactly the time that Harbin’s temple was being built, authorities in Suzhou were proposing the demolition of theirs so that it could be replaced with more “modern” urban enterprises: shops, thoroughfares, offices, apartments. A Confucian temple, in the Suzhou context, was renounced by Chinese nationalists who sought a modern nation.

But in Harbin there was, I argued in Creating a Chinese Harbin, a class of modernizing nationalists who saw, first and foremost, the importance of defining their city as Chinese. Many of these people contributed to the Confucian temple, the Buddhist temple, the city’s new private Christian middle school, and also the new public middle school that was the first public building in Harbin with a traditional Chinese aesthetic.

For the next three years, the Confucius temple rose. But while it was unquestionably a powerful symbol of Chinese identity, the nature of the Chinese state was under fierce debate during this time. This was the era of the Nationalists’ (KMT) Northern Expedition, an attempt to unite China after the Republican visions of Sun Yat-sen (孫中山 Sūn Zhōngshān) had gone off the rails. Isolated Harbin was one of the last arenas for the Nationalists’ vision to be contested, after much of the Nationalists’ project was already complete.

Harbin was not only isolated — far from the capital in Beijing, even farther from the would-be capital in Nanjing, and farther still from the KMT’s powerbase in Guangdong — it was also at the center of a strategically important area. Fertile farmland, mineral resources, ports, and proximity to both Japan and Russia made Manchuria especially important to nationalists who sought a unified and coherent China.

Confucius could be controversial for Chinese politicians. He certainly wasn’t modern, and his appeal to different political groups was far from uniform. But for politicians seeking to assert a Chinese identity against a Russian one or even a Japanese one, the 6th–5th century BCE philosopher fit the bill.

So it was at the temple’s opening ceremony, on November 28, 1929, that Zhāng Xuéliáng 张学良, the “young marshal” whose father had been China’s most powerful warlord for a time (and killed by the Japanese for his trouble), claimed Harbin as a Chinese place, with this temple as its symbolic center. At the temple, a stone stele records the speech he made: “Harbin is located on the upper reaches of the Songhua River, crossed by the Eastern Provinces Railway, and is a gathering place for merchants, travelers, and refugees from Asia and Europe, where the languages, customs, beliefs, and goods of travelers and immigrants mix together. After the recovery of self-government, there have been a hundred tasks…it has not been possible [until now] to spread the festivals and celebrations of the sage.’’

The political role of Confucius of course varied throughout the next century. For Chiang Kai-shek’s (蒋介石 Jiǎng Jièshí) New Life Movement, Confucianism was seen as an essential Chinese virtue, especially when melded with a Christian-flavored asceticism. Decades later, Red Guards targeted the Confucius family tombs in Shandong, attacking the primary example of the “four olds.” Then, the pendulum swung back once more, as the Communist Party promoted Confucius as a piece of its new nationalist identity, creating Confucius Institutes that would promote Chinese culture at universities around the world.

This later use — an attempt to paper over political divisions and ideology beneath a widely recognized but superficially understood symbol like Confucius — finds parallel with the Confucius Temple in 1920s Harbin, which sought to provide a lowest common denominator for all the city’s Chinese residents to recognize as theirs — and perhaps more importantly, not foreign.

This Week in China’s History is a weekly column.