Hope for Chinese soccer? How Shandong built a winner

It’s been a terrible two years for soccer in China, headlined by serious financial mismanagement in the Chinese Super League. But it's not all doom and gloom: just look at Shandong Taishan FC, Wuhan Three Towns, and Meizhou Hakka.

On October 27, 2010, Shandong’s top-flight pro soccer team — then called Luneng FC, since-rebranded Taishan FC — secured the Chinese Super League (CSL) championship on Honduran forward Julio César de León’s 74-minute equalizer against Nanchang. This was Shandong’s third title in five years, coming shortly after China’s professional leagues restored a degree of normalcy following a series of scandals and corruption.

Fans envisioned a long golden age for this Jinan-based squad. But it would be a different team to ring in a new era for Chinese soccer. In February 2010, the real estate giant Evergrande purchased the club from Guangzhou and immediately began pouring in money. Evergrande FC won promotion in 2010, then captured the next seven CSL titles, from 2011 to 2017. Other teams scrambled to keep up, and payrolls in the CSL skyrocketed. This was China’s era of “money soccer” (金元足球 jīn yuán zúqiú).

It would not last long. Things came crashing down soon after the pandemic hit in 2020. In the last two years, more than 20 clubs have bid farewell to China’s professional leagues. After winning the CSL in November 2020, Jiangsu FC folded four months later. Due to Evergrande’s financial problems, Guangzhou FC’s future is very much in doubt as well. It’s likely that they will lose all of their highest-paid stars, both foreign and domestic.

Chinese soccer this past season was desperate not just for a new champion, but a savior: a model franchise that domestic soccer fans could be proud of, and national soccer officials might be able to rely on.

Just like 11 years ago, Shandong rose at the critical moment once again. On January 4, a team led by both home-grown and international stars — notably captains Zhèng Zhēng 郑铮 and Belgian Marouane Fellaini — lifted the league trophy, an award they had secured three matches prior. That same week, Shandong claimed its seventh Chinese FA cup championship with a late goal from Brazilian Jadson (see GIF below), making the club a three-time domestic league and cup double winner.

How did Shandong succeed while more than half the league’s teams are reportedly having problems paying player wages? And could their success usher in a new era of responsible spending and competitive parity?

Shandong Taishan, founded in 1956, was one of the first clubs to carry out equity structure reform, a policy recommended by the Chinese Football Association (CFA) in 2015 to diversify a team’s source of funding. Taishan’s reform was planned out in 2020 with the Shandong provincial government, and the club is now owned by three state-owned enterprises.

The club has also benefited from prudent transfer decisions over the years while other teams were ravenously bidding for international talent. In 2017, Shanghai SIPG bought Chelsea’s Oscar for $68 million (more than 430 million yuan), making it the most expensive deal anywhere in that year’s winter transfer window. At the same time, Hebei China Fortune broke the transfer record for domestic stars by acquiring Zhāng Chéngdòng 张呈栋 for $23 million, a player whose market value has never exceeded $1.6 million, according to Transfermarkt. Shandong, meanwhile, received an estimated 500 million RMB ($80 million) from selling its players that year. For everyone else, the spending frenzy continued until 2019, when Guangzhou Evergrande was decisively the No. 1 spender in the global winter transfer market, moving more money than AC Milan and Chelsea. China News used the term “Great Leap Forward” to describe the mania.

Shandong’s patience paid off. It struck gold this past season, making the best value-for-money transfers in the league by signing Korean League MVP Son Jun-ho, Jadson, and Jí Xiáng 吉翔 (snatching him from the disbanded Jiangsu FC). Shifting toward a more sustainable approach has ensured Shandong will be a trophy contender for years to come, even if championships aren’t quite as guaranteed as they were for Guangzhou during its profligate years.

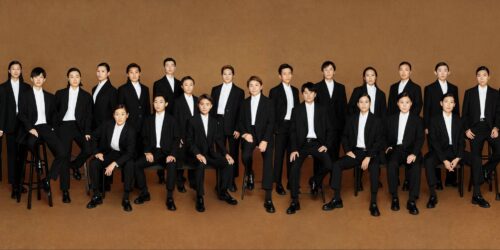

But it would be wrong to say Shandong’s on-field success was just the result of financial stability. Like many successful European clubs, Shandong paved its way with youth training. Back in 1999, the team’s Yugoslav manager, Slobodan Santrač (who led the team to a domestic double that year), helped Shandong establish a soccer academy that has since cultivated generations of gifted players for multiple clubs and the national team.

“I have to emphasize that my coaching staff and I are not here to change Chinese soccer but to invigorate and be part of it,” Santrač told the CFA in an internal meeting. “We need to pass on the most advanced soccer philosophy to our players and allow them to develop their styles.”

Twenty years on, Shandong is still on the same mission set out by their former manager: to invigorate Chinese soccer. Luckily, they are not alone.

Two clubs recently promoted from China’s second-tier League One have taken a similar approach, trying to build from the bottom-up: Wuhan Three Towns and Meizhou Hakka.

Wuhan Three Towns’ youth training scheme predates its soccer club. Supported by the local football association, Three Towns has been selecting and sending juniors to train in Spain since 2014. Its spending on youth training reportedly exceeds investments in the first team. Last month, 18-year-old Liú Shàozǐyáng 刘邵子洋 made headlines by becoming the first Chinese goalkeeper to play in Europe, when FC Bayern Campus signed him under a youth development contract.

Three Towns beat Meizhou Hakka 1-0 on December 18 to clinch the League One title. Founded only four years ago, the club now finds itself in the Super League. What’s more, it will join the CSL with a balanced ledger.

Meizhou Hakka, meanwhile, made history by becoming the first county-level team to qualify for the CSL — doing so in dramatic fashion. Desperately needing a point in the final game of the season on December 22 to fend off Zhejiang, Meizhou found itself down a goal to Kunshan FC. And then, in the 96th minute, on very literally the final kick of the game — with Zhejiang players having finished their game minutes before and lingering on the field to watch — this happened:

It was an emotional win (veteran Lú Lín 卢琳 was in tears during a postgame interview). A carnival atmosphere swept the streets of Wuhua County in Guangdong province, where the team is based, with fans marching on the streets while banging drums and gongs.

Wuhua is known as “the home to Chinese soccer,” as it supposedly is where modern soccer was brought into China by a missionary more than a century ago. According to the Meizhou government, 28.3% of Meizhou’s population either plays or follows soccer, the highest percentage in Guangdong. There are nearly 300 soccer fields and more than 150,000 registered players in the county. Local authorities also see soccer as part of the county’s cultural heritage. Meizhou showcases the best soccer culture and fanbase in an economically underdeveloped place, and it has just proven that a team with a small budget can compete in top-flight matches.

These two clubs have offered replicable templates. Along with Shandong, they have been exemplary in developing the sport from a grassroots level. Youth training provides a clear career path for players and raises awareness of the sport among the rank-and-file, something neighboring Japan and South Korea have greatly benefited from. It also echoes Xí Jìnpíng’s 习近平 ambition to foster homegrown talent to establish a soccer superpower.

But will authorities be patient enough to back long-term plans? One of the lessons offered by Taishan, Three Towns, and Hakka is that lasting success does not come overnight. Guangzhou Evergrande FC soared to never-before-seen heights, but it did so at the cost of the sport’s development in the country. Then again, will the CSL be allowed to matter? As Cameron Wilson wrote on this website last month in a scathing critique of the Chinese Football Association, “One of the least-recognized failures of Chinese soccer — among its many — is the way the CFA treats the CSL like a vassal at the service of the country’s soccer brand.”

COVID restrictions have also made things difficult: the CSL has played two seasons behind closed doors, with many games scheduled at strange times during workdays. Fan groups are having significant difficulties in recruiting new members, and the younger generation is feeling emotionally detached to their local teams, preferring iconic clubs in major European leagues. Some wonder if the damage is permanent.

But take a look at how Shandong celebrated its recent title: a video shot by soccer commentator Miáo Kūn 苗锟 shows a group of Shandong supporters gathered outside Tianhe Stadium in Guangzhou, where Taishan FC was playing the season’s final match. They livestreamed the game on their phones, unfurled championship banners, chanted and sang, then waited until their beloved players exited the stadium with the trophy. They enjoyed a brief moment to celebrate with manager Hǎo Wěi 郝伟 and their team. In this scene, you can almost see a picture of soccer as it’s meant to be: a team connecting a community.