In praise of Beijing 2022’s coolest venue, Big Air Shougang

Lots of snarky comments were directed at the site of the big air competition during the Olympics. But Big Air Shougang, an industrial park built around an abandoned steel factory, is a showcase for urban transformation.

Whether it was positive drug tests, strict COVID bubbles, or diplomatic boycotts, the Beijing Olympics were a magnet for controversy at nearly every level.

You can add architecture and urban design to that list (albeit slightly further down the list), with the surprisingly visceral international reactions to Shougang, the venue for the big air competition. Some viewers were put off by seeing cooling towers as the backdrop to pristine runs, commenting that this was a “hellscape,” or:

The Big Air stadium at the Olympics seems to be right next to the Springfield Nuclear Power Plant. pic.twitter.com/5CbedtGu3h

— John Lovett (@jlove1982) February 7, 2022

Honestly, what are we even doing here. pic.twitter.com/vtj7FarSVv

— Michael Antonelli (@BullandBaird) February 8, 2022

The critics missed the point. Big Air Shougang is an example of urban transformation — and it’s cool as hell.

I saw Shougang for the first time last summer after reading Jonathan Chatwin’s book Long Peace Street. Chatwin describes walking down this street — known in Chinese as Chang’an Jie, which cuts across Tiananmen — beginning from Shougang in the west, the Capital Iron and Steel Works that began operation in 1919. “Cathedrals of rusted steel loomed above and all around, pacifically awaiting their fate,” he wrote. “Faded barber-pole striped chimneys dotted the skyline.”

When Chatwin visited in 2016 for his book, Shougang had been closed for four years, and authorities still weren’t sure what to do with the site. “Vague but expansive plans for the redevelopment of Shougang were touted in the media after the closure, with the proposed division of the site into different areas, including a cultural and creative area,” wrote Chatwin.

More concrete plans came into view in the years after Beijing won the rights to hold the 2022 Winter Games, specifically to turn it into a mixed-use development. The designers left everything they could intact, including furnaces and smokestacks, and added greenspace, offices, and athletic facilities around the decommissioned factory.

It’s a “symbol of urban regeneration,” according to the International Olympic Committee. It’s “the most ambitious industrial heritage transformation project in Northern China,” claims one of its designers, while Arup Group, a huge multinational engineering and design group that helped in the early stages of the design, touts the project’s green credentials.

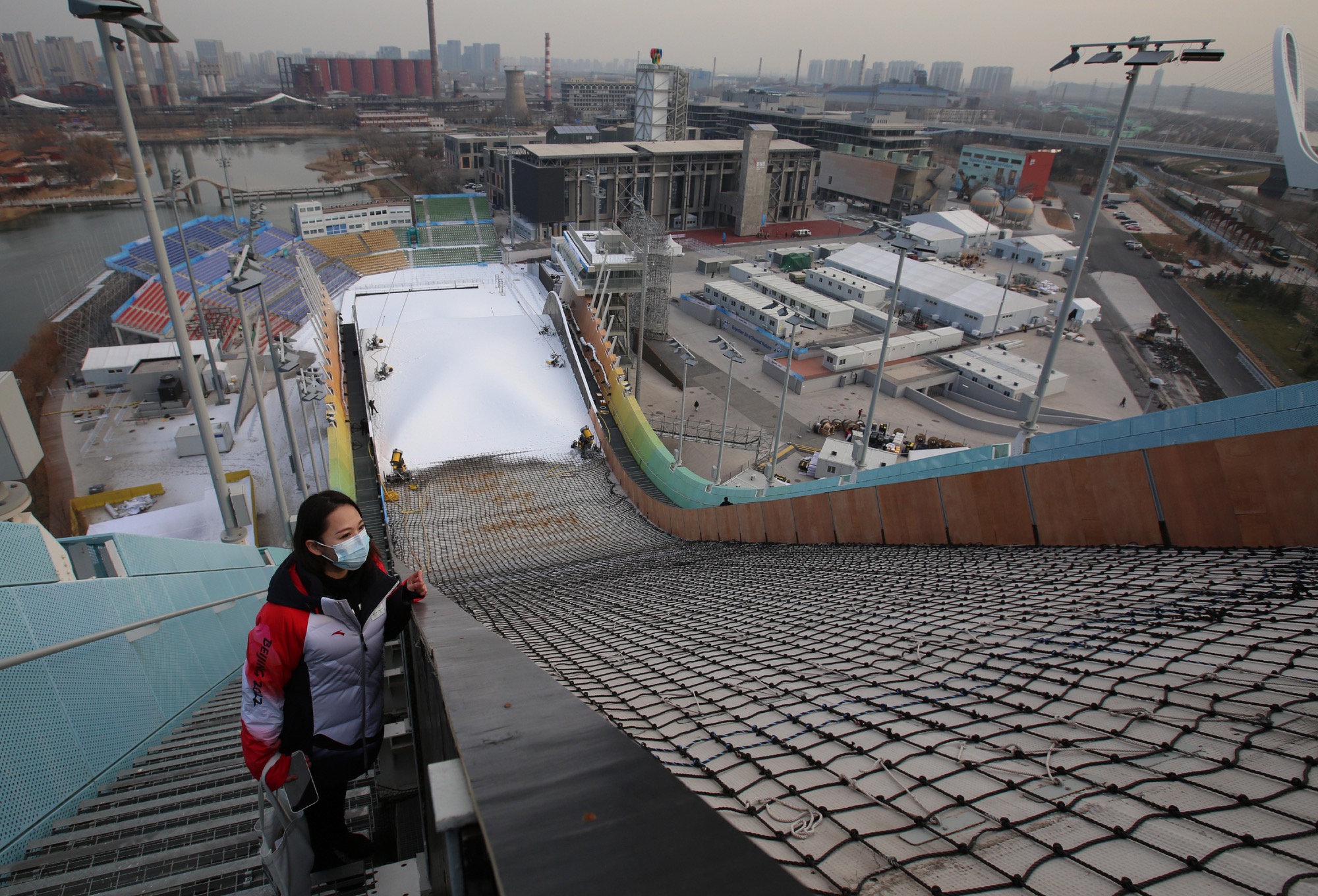

The centerpiece is a 164-meter ramp with a stadium that seats 8,000, the first permanent venue for the relatively new sport of big air jumping.

Rather than literally following in Chatwin’s footsteps and walking the 30 kilometers from my house to Shougang, I cycled. I stopped at the top of a new bridge across the venue that gave me clean sight lines to the big air run and the stadium that surrounded it.

If the juxtaposition of a Winter Olympics venue and a former steel factory seems odd, you should have seen the place last June. The multicolored run was empty of snow, and the surrounding field was dotted with trees, cooling towers, empty industrial buildings, and construction equipment.

A couple of months later, Shougang hosted Beijing’s winter sports expo. The cavernous halls featured exhibits ranging from gargantuan ski lifts to full-size ice rinks.

But the attraction for me was the exterior paths where I could take in the storage cylinders and spheres and pipeline frames, all of which had been scrubbed clean and decontaminated. What impressed me was that rather than hide the site’s history, designers made an inspired decision to keep it in full view. The result is a unique and inviting public space. I remember thinking that this place was going to blow the world away.

Belgian architect Nicolas Godelet is one of the site’s designers. In a recent interview for a Chinese website, he spoke about the concept for the venue (translation from Chinese): “We need to respect the industrial history of this place, and how to coordinate the appearance of Big Air Shougang with the four cooling towers,” he said. The concept was to “find a certain distance between the venue and the cooling towers, and the distance allows the big air to appear, and also allows the four cooling towers to appear.”

In other words, the derided decision to include cooling towers in the frame is a feature, not a bug.

The venue has hosted its share of dramatic moments over the last two weeks, from Eileen Gu’s (谷爱凌 Gǔ Àilíng) first gold medal to a controversial silver for China’s snowboarding phenom, Sū Yìmíng 苏翊鸣.

“The venue is fantastic,” said Gu, who won three medals in Beijing. “I mean, look around, there’s no snow anywhere else. And somehow when you’re skiing on this job, you feel like you’re on a glacier somewhere.”

“The first time I was on the top I was a bit disappointed, because when we’re at the top we usually see lots of mountains. But when the lights get on it’s really amazing,” said French athlete Antoine Adelisse.

The athletes seem to love it, but why has the reaction to Big Air Shougang been so divisive?

I put the question to Mark Dreyer, my cohost on the China Sports Insider Podcast. “[Viewers are] just reacting to what they’re seeing,” he said. “If they had it in the early evening with the setting sun, it looks stunning. It’s some of the most made-for-TV perfect shots. They have all the competitions in the early morning. I think they’ve really missed the trick.”

Chatwin, the author of Long Peace Street, added that Shougang’s redevelopment didn’t seem controversial to him before the Games, especially in view of similar projects in the UK, like the Battersea Power Station or Tate Modern redevelopments.

“Seeing it through the prism of the response online, you kind of realize that what happened was that it chimed with a kind of general feeling that maybe Beijing shouldn’t have been allowed to host the Games…which I kind of understand to some extent, coupled with…it seeming to confirm a kind of prejudice towards Chinese urban landscapes as being this kind of dystopian hellscape.

“I just ended up feeling that people are judging by a different set of criteria to that which they would judge urban redevelopment in the West, and I guess that comes down to it confirming prejudices that have already existed about the kind of environment that Chinese urban development has created.”

I think Dreyer and Chatwin are on to something, but there’s something else at play, too.

Beijing’s Olympics, even in the mountains of Zhangjiakou, rely completely on artificial snow. But in Zhangjiakou, you can at least pretend to be in a natural wonderland. Shougang dispenses with all that.

It’s not a hellscape, but its very existence subverts its green aspirations. As the world gets warmer and glaciers continue to disappear, it forces us to confront an uncomfortable truth: Big Air Shougang may be the world’s first permanent Winter Olympics venue of its kind, but it won’t be the last.