This Week in China’s History: March 29, 1974

In mid-March 1974, a group of farmers near Xi’an were digging a well. Six brothers and one of their neighbors, Wang Puzhi, had been seeking a new water source for some time. The oldest brother, Yang Peiyan, identified a likely spot, and the seven men began to dig a wide hole, some 15 feet across, expecting that they would be digging for some time in order to strike water. They wouldn’t find any water, but soon their digging revealed what can, without exaggeration, be considered one of the most important and impressive archeological discoveries of all time.

After just three or four feet, they struck hard, red packed earth, but didn’t think too much of it, and they dug through. After about a week they were 15 feet below the surface and began to encounter pottery shards of various sizes. This was not unusual in the region — settlement there had a very long history, and much had been buried over the years. And anyway, they were looking for water, not pottery.

On March 29, they uncovered what they at first thought was a large jar — not what they were looking for, but potentially useful. It was just the start of an unlikely series of events. Historian John Man describes what happened next in his book The Terracotta Army: China’s First Emperor and the Birth of a Nation: “Everyone crowded around, and there was a collective gasp…. Sticking out of the earth was a head: two eyes staring up at them, long hair tied into a bun, and a moustache. Someone touched the head with a spade, and they heard the dull thunk which told them it was intact, and very solid.”

The Yang brothers’ conclusion: “Completely useless, like all their other finds — and also bad luck because it came from underneath the ground, where the dead dwelled.”

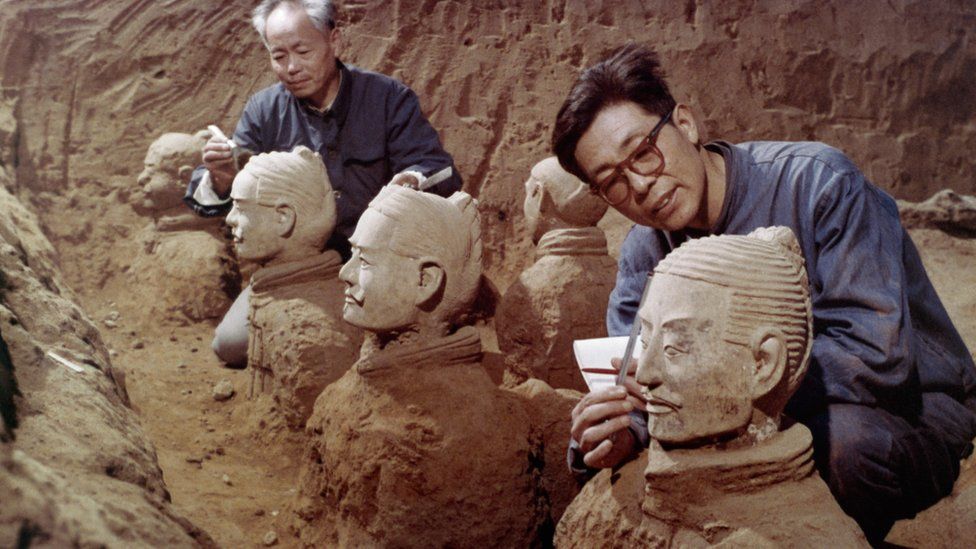

Over the next few weeks, more figures were dug up, along with arrowheads, bricks, and some bronze tools. Some were taken home by local residents as decorations, souvenirs, or scrap. It would be another month before reports of the discoveries reached the ears of Zhào Kāngmín 赵康民, a museum director in nearby Lintong. Zhao recognized that the figures were likely connected to the nearby tomb of the first emperor of Qin — Qin Shihuang — often credited as “China’s first emperor.” The tomb itself (as yet unexcavated) is richly described in historical texts, but no indication of an “underground army” hinted at what was there. Under Zhao’s direction, an excavation began that eventually led to the discovery of what we have come to know as the “Terracotta Army” of emperor Qin Shihuang: an estimated 8,000 ceramic figures of soldiers, hundreds of horses, as well as war chariots, carts, and other materiel. The figures were determined to have been buried around the time of the tomb’s construction: the decades leading up to the death of Qin Shihuang in 208 BCE. The site has been listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1987, and many millions of people have been to see it.

The scale of what was found defies belief. In three pits (a fourth pit has been excavated as well, but found to be empty) are displayed more than 6,000 soldiers, most of them standing infantry, but others kneeling archers. Approximately life-size — ranging from about 5′8″ to 6′ in height — the figures are differentiated by rank. While the bodies are made from a series of molds, of a standard size and style, the faces are highly individual. Some theorize that they were sculpted from life — which would mean tourists today are looking at the faces of soldiers who died 2,500 years ago — but the more likely theory suggests there was a set of 10 or so molds used to create differentiated faces. The figures were not entombed as the uniform red-brown color that is today synonymous with the site, but were brightly painted. Reds, blues, and purples adorned the figures when they first emerged from the ground, but oxygen and other conditions quickly degraded the colors so that within a few hours they took on the terracotta color that defines them today.

Zhao, who died in 2018, described himself as “first discoverer, restorer, appreciator, name-giver, and excavator of the terracotta warriors,” arguing that even though he had not found the first fragments, he was responsible for identifying them and piecing them together for the first time — often from hundreds of small fragments — and protecting the find in the waning days of the Cultural Revolution. A lawsuit by the farmers who first found the warriors, seeking credit for the discovery, was unsuccessful.

The terracotta army has become a powerful force for China’s public face in more ways than one. Its status as one of the world’s great tourist attractions is indisputable, generating revenue and public interest. The warriors also fit into a common, though misleading, narrative about China’s history. Qin Shihuang did successfully unite, for a short time, numerous states under his rule, and, as countless undergraduates have memorized for exams, the Qin dynasty standardized currency, the writing system, weights and measures, and wheel gauge across the empire, as well as building thousands of miles of roads (though not, as is commonly claimed, the Great Wall, at least not as we think of it today). And the title huángdì 皇帝 (emperor) did originate with the first ruler of Qin.

But despite these accomplishments, is Qin Shihuang overrated? His role as “first emperor of a unified China” suggests that there is some objective China that can be unified or divided. As I have previously written, referring to the writings of Jim Millward and others, this claim is at best provocative, and in many ways just wrong. Figuring out just what the “first emperor of China” means is a bit like peeling an onion. The boundaries of the Qin in no way approximate the boundaries of many subsequent dynasties, or today’s Chinese state. And earlier dynasties — is “kingdoms” the better word? — had enormous influence, like the Zhou.

Perhaps the most impressive legacy of Qin Shihuang remains hidden: a short distance from the terracotta army rises a small hill that covers the mausoleum of the emperor himself. According to the Han dynasty historical text Records of the Grand Historian (史记 shǐjì), the tomb includes a scale model of Qin Shihuang’s dominion, with rivers and lakes filled with mercury and circulated by pumps, all protected by elaborate booby traps and defenses that would thwart Indiana Jones. The terracotta warriors were damaged by fire, and fear of grave-robbers is constant when considering the fate of antiquities, but there is reason to think Qin Shihuang’s grave remains undisturbed. The mausoleum remains sealed, in part for fear of how its contents would be preserved once exposed to the elements, but radar imaging suggests that the contents are intact. The most recent surveys suggest that the mausoleum encompasses a vast 38 square miles, and includes clues not only to the emperor’s life and death, but the power struggle that ensued over his succession.

In several trips with students to Xi’an, the terracotta warriors was one site that never disappointed. Even smaller exhibitions, such as one recently at Philadelphia’s Franklin Institute (where the thumb of one of the warriors on display was stolen!), never fail to attract fascination and encourage questions, even if Qin Shihuang’s legacy is both complex and oversimplified.

This Week in China’s History is a weekly column.